The group exhibition, A Thought Is a River at the Carnegie (Covington, KY) gathers and places both sculpture and painting in collective relationships to one another. Some works appear to be excavated from deep within the earth, while others are industrial and integrate artificial structuring. Collectively, the work undulates the passage of time; their materials reference an array of seemingly found or discarded objects, against smooth, gleaming forms that peer into the future. The exhibition’s play between these works contrasts one another through the possibilities of utopia and dystopia, diverging paths through their approach to material and its construction.

As you enter the gallery, the expansive high ceiling looms over the viewer with works situated both on the ground and walls. Dale Jackson’s Untitled works are difficult to ignore during the viewer’s sweeping glance of the exhibition. The intensely saturated paper attached to the back wall establishes a grid, with written text on each individual square. Jackson’s flow of consciousness reads, “John Walsh of America’s most wanted go after worst of the worst Flip Wilson. What you see is what you get Lincoln town car four door hardtop the end’. Moving between references of paranoid crime television and the hilarity of a car salesman, Jackson invokes the poster’s signage often seen on the side of the road offering empty promises of commodities, jobs, and housing – there always seems to be a catch.

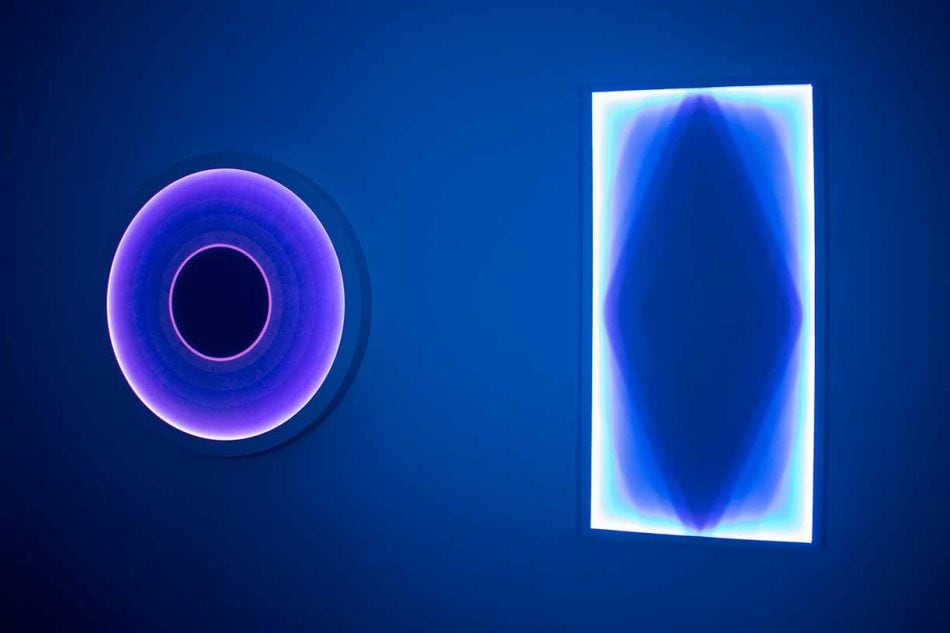

Adjacent to Jackson’s grid is Letitia Quensenberry’s circular, polished, and reflective surfaces. Also heavily saturated, they appear as industrially materialized droplets across the wall. These surfaces absorb light as their work on the second-floor projects it. Repeating, hypnotic rectangles and circles attached to the wall rhythmically change color; blue to violet, orange to red light travels downwards as it appears we are seeing it fall away into a darkening abyss. Akin to their titles, Hyperspace 21, 36, and 37 suggest futuristic mythologies of traversing an unknown, otherworldly space. In a smaller gallery across from Quensenberry’s work is a more familiar representation of mythos through the ceramic sculptures of Chris Hammerlein. The ceramic sculptures weave organic emblems of coral, sea turtles, cattle, and other figures into fluid relationships stacked almost on top of one another. The sculpture’s construction is highly detailed, and the surfaces retain an impression of the artist’s hand through intricate carving. Their timeless presence seems to move back and forth between the adoration of earthly creatures, and a lingering dread of uncertain futures.

Letitia Quesenberry, Hyperspace 36, 2019, wood, lacquer, LED, acrylic, 48 x 24 x 3 inches

Chris Hammerlein, Mother of God, terra cotta, 16 x 16 x 19.75 inches

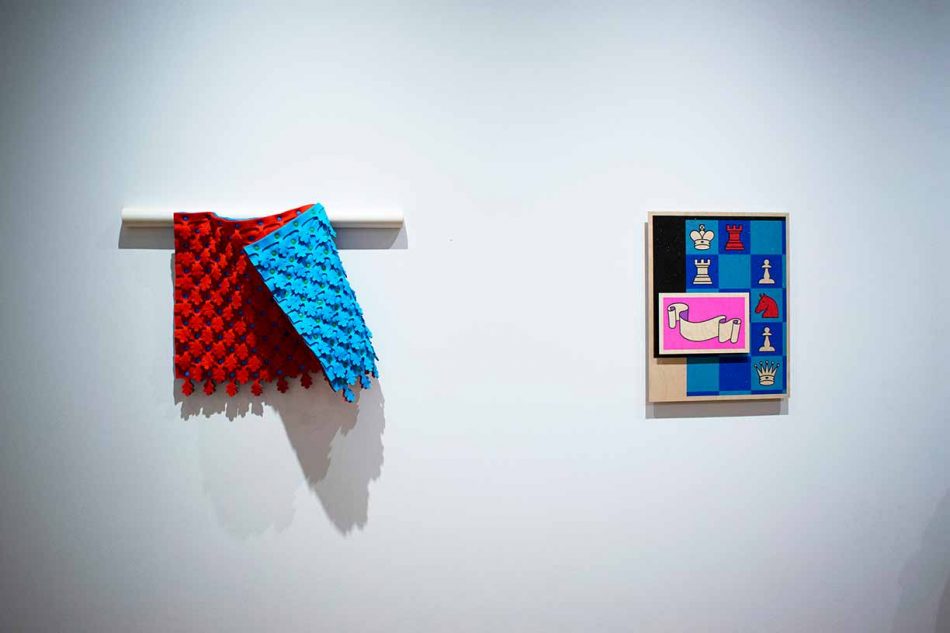

As you walk away from Hammerlein’s works, you enter another gallery that abruptly pushes against the natural brown tones of the previous space. The walls are filled with concentrated and bright color structures of Matt Coors’ works. The attention to detail is impressive, feeling as though they were almost mass produced with their rigid structures and repetitive, even patterning. This rigidity is challenged in the structural wall pieces through a movement similar to drapery; waving and folding back onto each pattern to accentuate hidden layers seeped in shadow. Next to it, Coors’ paintings also abide to an artificiality, with vibrating, sandy textures of painted chess pieces against photographs of plants and butterflies. Both realms of work seem to be concerned with the inflexible differences between materials alluding to mass production, and their final form of animation through motion and image.

Matt Coors, Arabian Mate, 2022, sand and adhesive film on panel, 17.5 x 22 inches

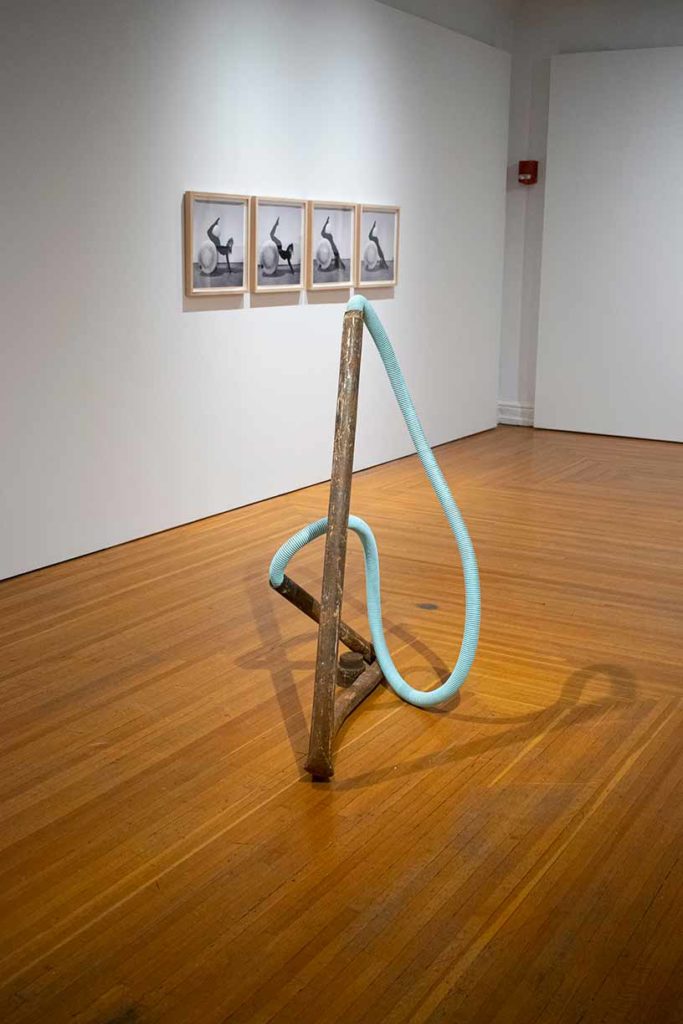

Across the room, Kiah Celeste’s floor sculptures act almost like deconstructed machinery, a vacuum hose is attached to a steel rod that is more or less the same width. The steel’s texture is rough, as though it’s been worn down over many eons. The scraps and accumulated rust imply an interference, as though this entity has been haphazardly dragged and thrown around – it has endured a brutal journey. The hose attached interrupts this natural process of deterioration and carries a different kind of weight; one that is loose and malleable. Their connection results in a gesture of water spilling out of the material, forever swelling as they will never become detached from one another. On the wall, Celeste’s photographs mirror the floor sculpture as her body begins to wrap around, over, and above an exercise ball. Four configurations of movement progress into a full extension of her arms and legs, imitating the same shape as the vacuum hose.

Kiah Celeste, Endless, Nameless, 2020, steel pipe, steel, vacuum hose, pigment, 38.25 x 15 x 54.74 inches

Returning to the first floor of the gallery, many of the sculptures are placed directly on the ground, or close to it. The viewer is forced to tip their body over, around, and through these objects. Albertus Gorman’s collections of found materials from the Falls of the Ohio display a dystopian excavation. Rusted paint cans are engulfed by spray foam as though they have risen from deep sediments, freezing an industrialized moment of time. Next to it, a circle is formed out of bird statues – plastic ducks with sunglasses, and a wooden goose painted entirely black. As the statue’s face away from the circle’s center, it feels like they are defending something or huddling together to deter our intervention. We are forced to focus on the contrast between the illusion of a real duck, and the saturated, commercialized version – sunglasses and all.

A Thought Is a River posits that the passage of time unveils both the dystopian, discarded objects of our present, and the luminosities of industrial materials that suggest the promise of a gleaming future. The artists included have produced work that impressively confronts questions of tactility, commodity, waste, and fluidity. Without providing a distinct solution, we are left with almost an offering – the objects we have imprinted onto the earth.