I first learned of this exhibition when Dayton, Ohio photographer Lloyd Greene sent me a photograph he’d taken of the wall text accompanying it. However, on searching the Columbus Museum of Art’s website I found no mention of it. When the museum confirmed it was there by phone, I forwarded the photo of the wall text to about 40 photographers around Ohio to let them know about it. Within a day I’d had emails from ten of them, including several from Columbus, grateful to learn of it.

So, intrigued by the decision to combine work by these three photographers in exhibition – who on first consideration seemed so different to me – I drove from Cincinnati to Columbus to view it myself (combining a few other tasks in the region, including another exhibition I plan to review in a later issue).

The apparent reasons the exhibition did not initially make the website is that it’s relatively small – about two dozen prints – confined to a single gallery (Gallery 5), and drawn entirely from the Museum’s own significant collection of photography. I am happy to report the exhibition is now on the website in the “On View Now” section (although without any opening or closing dates; the best information I could obtain from the museum is it’s “on view until November”).

The Museum’s Curatorial Fellow Sarah Berenz, met me at the museum and spent some time with me viewing the exhibition (the CMA was closing early that day to set up its “Wonderball” program, so time was tight). Sarah curated the exhibition and explained the initial intent was to do only a Diane Arbus installation, but she’d felt it would look too sparse, as there was only a ten-print portfolio and three other prints to draw from. She decided to add the work by Sherman and Woodman to create an exhibition by three female American photographers, stretching the time frame from Arbus’ period (the early 1960s to ’71) to the late 1970’s up to 1980 (both Sherman and Woodman’s work’s time frame).

Of the three, only Cindy Sherman lived more than a year past the date of the latest photograph included in the exhibition (and lives still, extremely productively), with the other two having both died by suicide. Is this something which should connect them? There does seem to be a kind of darkness of mood in much of their work, although their approaches to photographing are very different. Sherman’s darker work would not emerge until later in her career; this is her early landmark work, collectively identified as Untitled Film Stills and neutral in emotional tone.

The descriptive wall (and on-line) text for the exhibition contains the following sentence in its opening paragraph: “At a time when photography was regarded as less important than painting and sculpture, these artists were pushing the limits of the medium to create innovative practices and perspectives.” As someone who was around at that time, I have to disagree with the first part of this retrospection as a blanket statement. The photo boom of the ’70s was well underway when Sherman and Woodman were making their work, and both had Fine Art photography degrees to prove it (Sherman from Buffalo State University and Woodman from Rhode Island School of Design). As for Arbus, photography as an art form was well established at a museum level in New York City, where she lived and worked. Already in 1959 her work was included in The Family of Man exhibition at New York’s Museum of Modern Art, curated by Edward Steichen, who began directing the Museum’s Photography Department in 1947. In 1963 Arbus was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, renewed in 1966. In 1967 her work joined that of Lee Friedlander and Garry Winnogrand in MoMA’s John Szarkowski curated New Documents exhibition and catalogue. And in 1972, the year after her death, her photographs were featured at the Venice Bienniale, where they were “the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion.” That same year she received a solo retrospective exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, which was at that time the most highly attended exhibition in MoMA’s history. Photography as a fine art was firmly on the US cultural map in the ’60s and ’70s (even included as one of the original departments when MoMA was planned in 1929). While Arbus was making her photographs in this exhibition I was obtaining my own Fine Arts degrees in Photography. So, things were already shakin’.

I would agree that all three women contributed mightily to photography’s continued and growing appreciation as an art form. However, beyond medium (black and white photography), sex (female) and suicide (two), how to connect the three as an exhibition still somewhat eluded me. Finally I settled on two other aspects: performance and New York City.

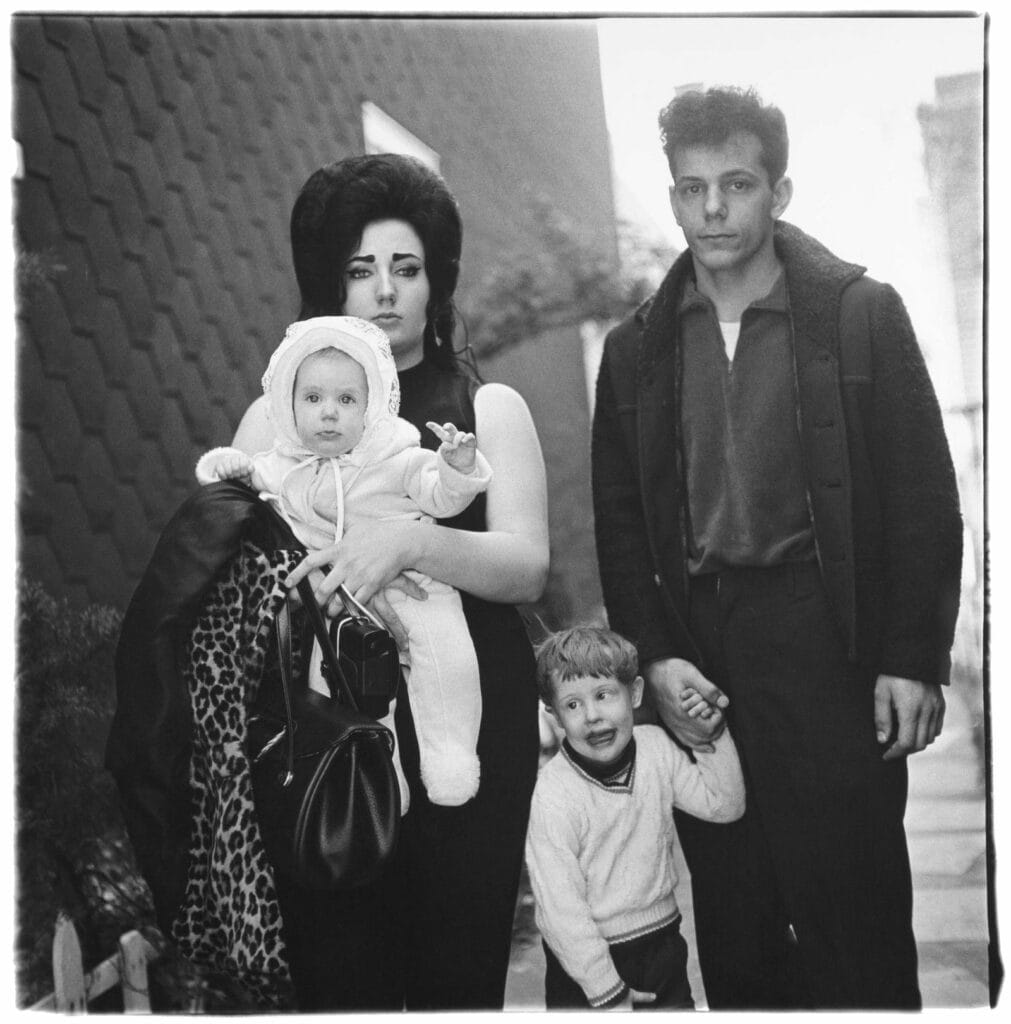

Entering Gallery 5, you are initially confronted by the ten Diane (pronounced “Dee-AHN”) Arbus portfolio portraits, hung in two rows. These are the most difficult to identify as performative, perhaps, but they certainly perform. After nearly 60 years they still almost jump off the wall. They caused a sensation in their time. Their in-your-face power, centered in the square formats of her Rolliflex or Mamiyaflex (often lit with two side mounted flash units), is reached by no other photographer of her time, except perhaps Avedon (who was her friend and an influence); but Arbus breaks the glass window into an non-studio reality that startles, almost making Avedons seem artificial. Arbus’ interest in marginal individuals and “freaks” caused charges of exploitation to be leveled against her (of course all photographs exploit their subject matter somehow); but her fascination was misunderstood. A quote of hers I have long carried in my memory goes something like this: Most people go through life dreading they’ll have a traumatic experience. Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. That’s what make them the true aristocrats.

There is love in these photographs, although they apparently provoked discomfort in many who viewed them (perhaps they still do). Even though her subjects rarely were performing for her camera – they were just being who they are – Arbus’ straightforward acceptance of them creates a kind of performance space from which her subjects emerge compellingly (often seen from a foot or so below eye-level, due to her using reflex camera, suspended from her neck, adding a slightly monumental feeling to some of the portraits). And while these pictures are first and foremost about their subjects, the choice of the subject and way each is engaged tells us much about the photographer as well.

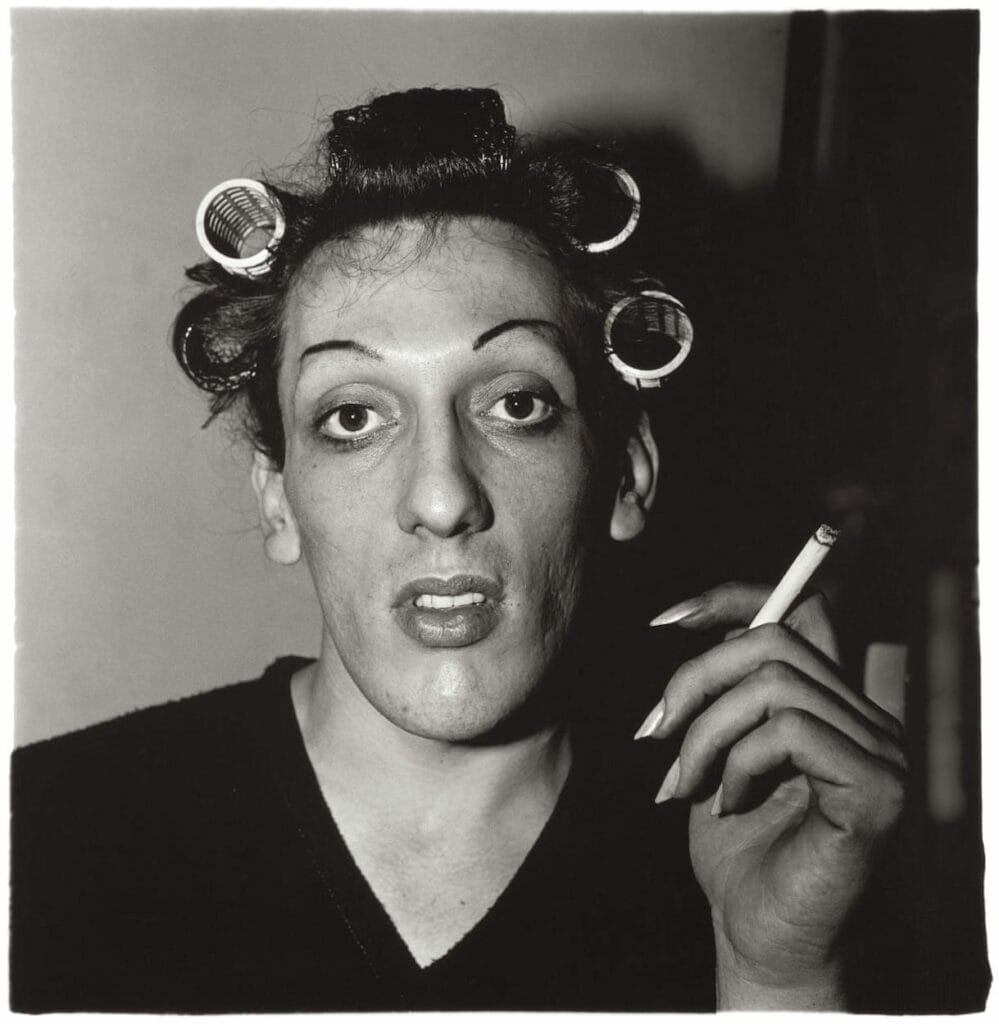

“A Young Man in Curlers at Home on West 20th Street,” pictured here is slightly atypical of Arbus’ style, more contrasty, almost harsh, side lit with a deep shadow. There is informational contrast as well, with the man’s pitted skin and cigarette contrasting with his perfect fingernails, finely plucked eyebrows and intentionality of curlers. The photograph was taken in 1966 and included the 1967 New Documents exhibition at MoMA. It may have been many viewers’ first encounter with a NYC transvestite.

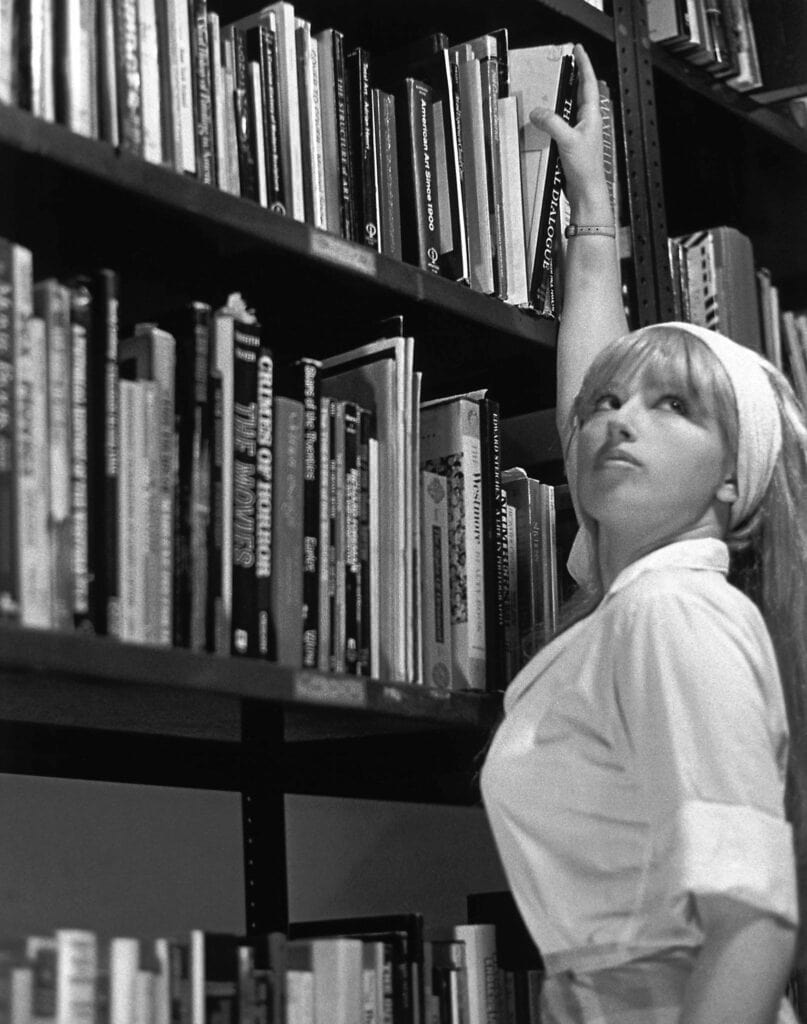

The performative aspect is more direct in the Sherman and Woodman photographs, which are also connected in the selected subject matter of both being the photographers themselves. Both bodies of work pre-date “selfies” yet neither are exactly self-portraits. I would call Sherman’s early photographs self-portrayals, in that she uses herself to portray a character or type, while emulating the look of photographic “stills” made to promote films, especially B movies or foreign cinema – re-creations of contemporary archetypes. In the year following her photographs in this exhibition, she would begin using color and rear-projected backgrounds, emulating another cinema technique, itself imitating three-dimensional reality. They represent an evolution from Arbus’ work, build well on photo documentation of the performance art of the 1960s and are perfectly situated in the emerging post-modern art era of the ’70s (and she produced 70 Untitled Film Stills).

I have a confession to make here. Sometime around 1980, before I’d heard of Cindy Sherman, let alone seen her work, I received a black and white photographic postcard of a woman sitting in an open window with a fire escape behind her. I didn’t know who she was or whether I knew her (or she knew me) but there was something very accessible and seductive about the woman pictured that led me to write back to whatever address was on the card, wanting to meet her. I think it likely was from Sherman’s first solo exhibition in New York City, at the Kitchen. I don’t know whether the photograph was from the Film Stills series or was simply a photograph of Sherman as the exhibition’s artist – I’ve not seen the image again. If an artwork, it’s likely the intention was to project seductiveness and accessibility, which worked on me more personally. It’s a bit embarrassing, all these years later; but I’m not sorry I did it, even though the woman in the photograph never replied (I imagine Sherman received many similar responses; at least I hope I’m not the only rube who fell for the early ruse).

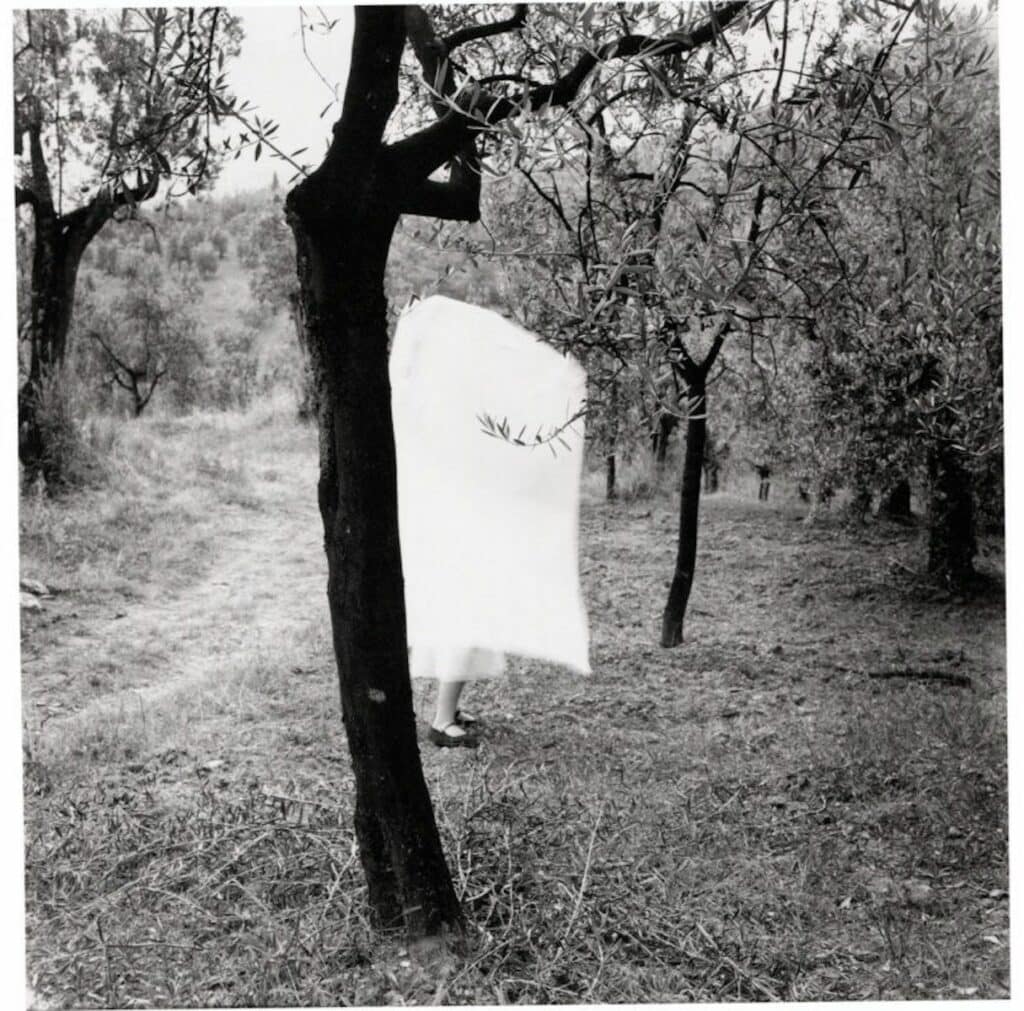

Francesca Woodman’s art is also performative, in that she stages her photographs using herself as the performer. But they are not intended as referential to films or anything other than her own inner reality. This is not to say that one can’t find references to the work of other artists – Man Ray, Duane Michaels, Andre Breton, the Symbolist Max Klinger, are some (note Max Klinger is a character’s name on the TV program M*A*S*H*, in which another character, psychologist Dr. Sydney Freedman, is played by Allan Arbus, Diane Arbus’ husband and photographer partner, from whom she received her first camera). But these references are among her tools, not the point of the works. Unlike the intentionally bland neutrality and personal anonymity of Sherman’s work, Woodman’s work probes her subconscious in creating her photographic realities, often set in anonymous rooms, emphasizing their interiority. Because of this it has been characterized as Surreality; but although susceptible to the influence of the Surrealists, I’m not sure that’s where I would put it categorically. One characterization that feels closer to the mark is thinking about it as Gothic fiction (reportedly she identified with Victorian heroines).

Like Arbus, Woodman preferred a medium format 2¼” square camera, with which she produced over 10,000 negatives in her short career and life. Like Arbus her life was marked by cultural privilege (studying in Rome, family summers in Italy, private boarding schools) and, like Arbus, she killed herself in New York City, leaping from the window of an East Side loft, aged just twenty-two (Arbus did it in a bathtub in the West Side artists’ coop Westbeth). Cults grew up around both women. In Woodman’s case, the fascination continues strongly. In almost every fine art photography class at an art school or university there are usually two or more students who essentially want to be Francesca Woodman, perhaps in part identifying with her youth – having made much of her work while still a student – her prodigious output, her self-obsession, introspection, depression and dramatic end, and her extraordinary fame. I don’t entirely know; I’m not a twenty year-old female student. Her work is not unlike many female student’s self-exploratory work in the late ’60s through the ’70s, but pushed unflinchingly, prodigiously, relentlessly until it can’t be dismissed or denied. (Another aside: Francesca’s older brother Charles Woodman until recently was an Associate Professor teaching electronic art at the University of Cincinnati.)

There are a couple photographers (still living) who come to mind whose work resonates similarly to Woodman’s which I suggest seeking out and appreciating: Arno Rafael Minkkinen’s self-portraits in landscapes and Anne Arden McDonald’s early staged self-performances (the former most like the atypical, outdoor Woodman image below). Minkkinen began his work in the late 1970s and continues to the present, while McDonald’s related work was made between late 1980s and the mid-1990s.

The exhibition Arbus • Sherman • Woodman: American Photography from the 1960s and 1970s continues into November at the Columbus Museum of Art. For help planning a visit, call 614.221.6801 or visit https://www.columbusmuseum.org. All photographs courtesy the Columbus Museum of Art.

“William Messer’s review of Arbus/Sherman/Woodman: American Photography from the 1960s and 1970s at the Columbus Museum of Art is a very fine review, deeply informed, thoughtful, & illuminating with all sorts of good points made throughout. Just one of several nice touches is the useful distinction between portraits & portrayals. The correction of the glib misperception of the role of photography in the wider realm of visual arts was also welcome.”

– Sean Wilkinson, Professor Emeritus, University of Dayton