Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, Ohio

On view through August 14th 2022

Fires are raging out west now, caused by years of draught. Need water! In 2014, Flint has a life-changing catastrophe of lead contamination in the city water supply. Monitor water safety! Flooding jeopardizes coastal areas worldwide. Ocean waters rising! Headlines every day. Water is and always has been crucial to the planet’s survival and all that grows and lives on it.

This timely and well-researched exhibit offers the viewer a host of thoughts and issues that arise after examining the fourteen different artists and each artist’s approach to using water and themes of fluidity, connectivity, and resistance. Among the issues that the artists address are water rights, climate change, and the effects of natural disasters. There is interplay with bodily issues and the exhibition title ‘breaking water’ of course refers to a mother’s water bag breaking, signaling the beginning of the birthing process – featured in a multi-monitor video installation. A film-screening program that extends the exhibition’s central themes compliments the exhibition.

Before water, there was Land Art. Land Art, variously known as Earth Art, Environmental Art, and Earthworks, is an art movement that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. During this period of dramatic unrest, political actions and social protest, land art sought to critique and rail against the overt commercialization of art and culture. Through its very nature, land art could reject the museum or gallery as the accepted venue to host and investigate artistic production and as such it closely overlapped with some of the concerns of minimalism. This emergent art trend would not have gained traction without the burgeoning ecological movement of the era with which it dovetailed. Land art is revered since it often espoused various utopian and spiritual yearnings for Planet Earth as the home of mankind. Three of its legendary practitioners are Robert Smithson, Nancy Holt and James Turrell. Smithson and Holt created the Spiral Jetty, now compromised by the aforementioned draught out west.

The fourteen artists curated for Breaking Water are resting on the shoulders of such giants as Smithson, Holt, Turrell and others, and though the curators may not have seen it from this perspective, I do. Breaking Water brings together art works in installation, video, photography, painting, sculpture, and performance that offer a range of approaches to the subject of water, liquidity, and feminism. A feminist/earth-embracing approach permeated much of Land Art’s creations and it is fitting that the exhibition curators selected artwork with a feminist philosophy here as well.

What is wonderful about this thoughtful exhibition is how much it calls up art and art actions from the recent past and present, bringing to my mind dozens if not hundreds of significant artists who care about earth’s resources. Think Andy Goldsworthy, an anti-Warhol cadre if you will, even if one of the exhibition’s sponsors is the Andy Warhol Foundation.

The entire exhibition is beautifully organized with ample room between works. Some art, such as Cecillia Bengolea’s vinyl printed figures mounted on wood that are engulfed in a dynamic sea-creatures video are in a cozy niche in the back of the gallery. I question that these figures are feminist. They are kitchy and maybe would have more impact if they were larger or perhaps fragmented. The video projector was mounted just below the ceiling to flash over and around the figures and onto the two back walls creating a captivating installation overall.

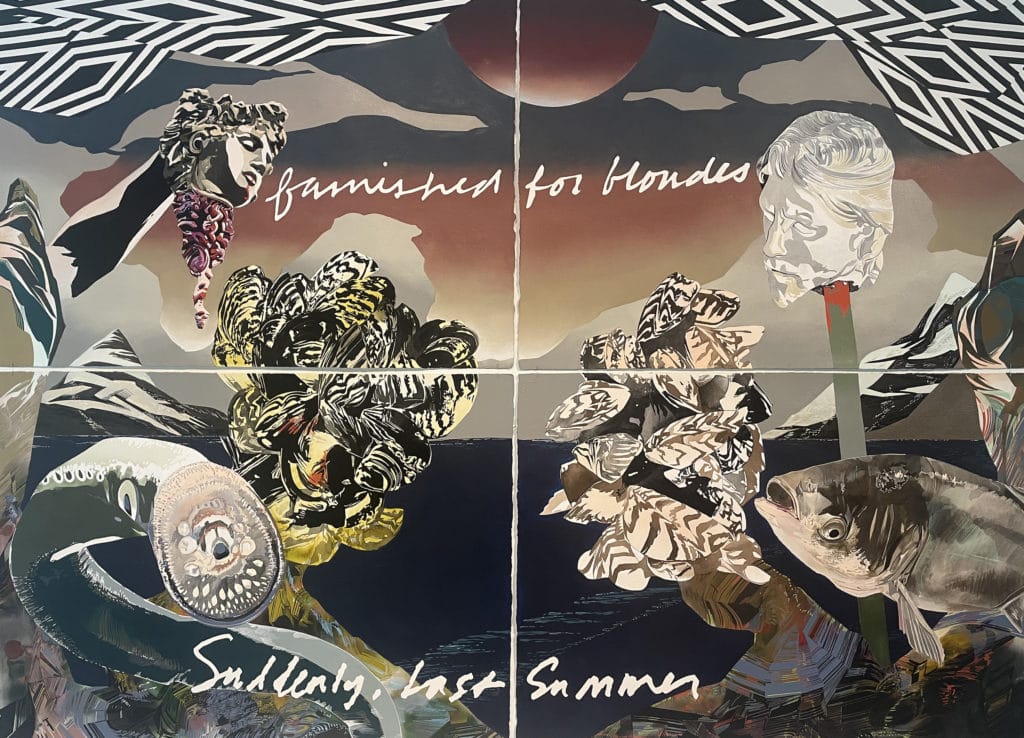

Andrea Carlson, who is a Grand Portage Ojibwe, embraces the loss of ancestral lands by painting lost imagined landscapes such as Portage. She further ramps up her critique of European land grab in America with Famished for Blondes. Unpacking this includes artistic script, aquatic life that is rather literally disconnected from the severed Medusa and European head above and smart black and white chevron borders. What is she really trying to get at here? I am looking at a smart painting full of disconnected or barely connecting references. Adjacent to these works is Atrato by Marcos Avila Forero, a captivating video of tamboleo: drumming on water. The Columbian participants who are joyfully slapping the water are in contrast to the wall text regarding armed conflict in Columbia, the residuals of slavery and various territorial struggles. The video and text don’t match but the video is loud and joyful, bringing a dynamism to the exhibit that is at times too synthetic in feel. All the videos in the show are interesting to be sure.

The synthetic feel permeates the large metal window/stone/wood installation by Claudia Peña Salinas. The work is taken from the New York City harbor and waterways. Everything is scrubbed clean. The manufactured windows show us what? If Ann Hamilton made this installation, we would smell the seaweed. Where are the smells, the messiness, and the nature of nature? Finnish artist Jaana Laakkonen breaks with the synthetic feel of much of the work in the exhibition with ethereal scrims of either polyester sheer curtains or thin burlap/linen in several of her works. It is a stretch to call her work “liquid” but there is an airy fluidity and ethereal feel to these works, with such a light touch with thin pigment or bits of sewing. There are works like this in the Nordic countries and the influence of more darkness half the year, more light the other half, and being on large peninsular land masses still wooded all contribute to a calm and reflective kind of art work.

The only weak work is the Paul Maheke installation Unresolved Shadows and Reflections. It can’t compete in terms of aesthetic involvement and conceptual richness with other works. The Ubonas’ The Swamp Game is a heavily researched wall installation on the history of wetlands (to put it is the simplest terms.) It has the depth and complexity of Bernd and Hilla Becher’s Wasserturme (Water Tower) Series and it is worth reading carefully.

The artists in Breaking Water include: Martha Atienza (b. 1981, Bantayan, Philippines; lives and works in Bantayan, Philippines), Marcos Ávila Forero (b. 1983, Paris, France; lives and works in Paris, France), Cecilia Bengolea (b. 1979, Buenos Aires, Argentina; lives and works in Paris, France), Andrea Carlson (b. 1979, Grand Portage Ojibwe, USA; lives and works in Chicago, IL)

Carolina Caycedo (b. 1978, London, UK; lives and works in Los Angeles, CA), Jes Fan (b. 1990, Ontario, Canada; lives and works in New York, NY), Cleo Fariselli (b. 1982, Cesenatico, Italy; lives and works in Turin, Italy), Saodat Ismailova (b. 1981, Tashkent, Uzbekistan; lives and works in Tashkent, Uzbekistan and Paris, France), Jaana Laakkonen (b. 1985, Joensuu, Finland; lives and works in Helsinki, Finland), Calista Lyon (b. 1986, Nagambie, Australia; lives and works in Charlottesville, VA) and Carmen Winant (b. 1983, San Francisco, CA; lives and works in Columbus, OH), Paul Maheke (b. 1985, Brive-la-Gaillarde, France; lives and works in London, UK), Josèfa Ntjam (b. 1992, Metz, France; lives and works in Saint-Étienne, France)

Claudia Peña Salinas (b. 1975, Montemorelos, Nuevo León, Mexico; lives and works in Brooklyn, NY), Vian Sora (b. 1976, Baghdad, Iraq; lives and works in Louisville, KY), Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas (collaborators since 1997; live and work in Vilnius, Lithuania and Cambridge, MA.)

All photos taken with permission by Cynthia Kukla.