There is a defensive power to classifying actions as “performance”—we can all make a choice to perform, and to craft that performance carefully with the full reassurance that it isn’t necessarily our real selves. A portrait is a permanent performance, both for the sitter and the artist. And when the portraitist is as masterful and expedient as John Singer Sargent, the sitter did not need to worry that their visage will make a statement.

“Portraiture and performance” frames one section of the “Fashioned by Sargent” exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which includes about a dozen garments worn by sitters. This section takes the “performance” aspect quite literally, showcasing portraits of stage performers—ones that Sargent pursued independently of commissions, chasing his passion for their mutual artistry—and socialites donning “exotic” costumes.

“Ellen Terry as Lady MacBeth” is a standout here, not least because of the ravishing costume placed beside it, replete with shining blue beetle wings. Sargent has posed the actress uneasily holding a crown above her head, anticipating a rise to power that will never come. This pose did not appear in the action of the play, for which he was present on the opening night, instead it is an interpretation that mingles both the meaning of Shakespeare’s play, the actress and her garb, and Sargent’s own skills. He also changed the colors of her dress—a performance of permanence for his version of the actress and dress.

In “Fashioned by Sargent,” we are mostly situated in wallpapered galleries that suggest the living spaces of wealthy patrons, not the stage, although “performance” permeates no matter the setting. The exhibit immediately puts a metaphorical velvet sack over viewers’ heads till we are ejected into a bright “plein air” gallery featuring mostly outdoor scenes after Sargent retired from commissioned portrait-making.

Such a brazenly pretty historical show would not typically be high on my list of must-see art experiences for 2023. But it’s a clever framing, and not only because its loveliness has been drawing enormous crowds. The curatorial work here is deeply humanizing. With the masters, including now-renowned Sargent, or anything antiquated, modern audiences are more likely to accept these pieces as plucked from the ether. How exhilarating to picture oneself as part of the process, to see the human element that casts these portraits not as relics but as working collaborations, pieces of an actual vibrant past.

For instance, one sitter had prepared several high-fashion choices for the artist, but he asked her to wear her more plain black “house” dress. Or, the aforementioned extra fabric: dramatically- dressed subjects weren’t always wearing huge, shimmery dresses with peaks and valleys in the fabric that played with the light. Sargent just knew his strengths as an artist, knew what he liked to paint, and knew how the texture and colors would best interact with the sitter’s surroundings. So these rich ladies and girls sometimes had a bolt of fabric draped over their couture.

It’s those artistic choices that this exhibit celebrates and explores—a welcome angle that invites the viewer to think like an artist. His portrait of teenager Elsie Palmer (1889-90) is the result not of a different dress, but a different location. Sargent first thought to paint her in a large hall before choosing a wood-paneled wall that echoes the pleats in her dress. The artist’s choices—Palmer’s straightforward gaze, the staid wood paneling background—give an arresting impression of a debutante waiting to confess in the principal’s office.

The garments themselves are also a prominent part of the exhibition, although nowhere near in number as the paintings. Their inclusion allows us to see the sometimes controversial liberties Sargent took with a sitter’s garb. A red velvet dress almost identical to the one worn by Mrs. Charles E. Inches in her 1887 portrait is not as nearly as revealing as the version in the portrait. One of the many delectable quotes of social reactions to these portraits was about this piece: “I think Mrs. Inches looks as if she would bring out the head of Holofernes for the asking,” wrote Fanny Lang to Isabella Stewart Gardner.

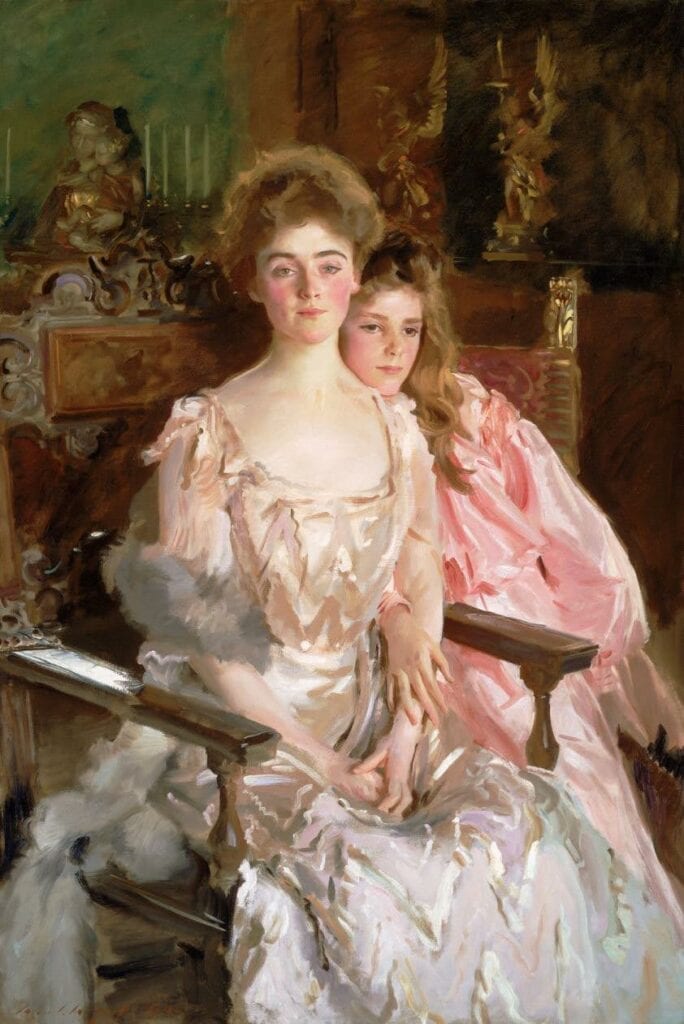

Although the show focuses on fashion, I found the subtle gestures and postures of sitters to be their most moving quality. Alice Thursby, a free-thinking champion of art, appears in sort of a crouch, as if she is ready to spring from her chair and into action; Lily Millet sort of hunches over, grasping a lilac shawl, looking both vulnerable and comfortably casual; one critic noted that Adèle Meyer, pictured with her two children, looks like she is about to “slide out of the picture.”

There are hints of Sargent’s subversiveness noted in the placards, namely his kinship with “outsiders” like artists of all backgrounds and wealthy Jewish families who were not accepted into all aspects of society life, not to mention his known but never frankly stated homosexuality. But the show goes down easy. I knew before going that it’d be the perfect place to take a senior citizen on a date—what I didn’t know is how much I’d enjoy learning more about Sargent, his sitters, and pondering the collaborative artistic relationship between painter and sitter.

The exhibit is open through January 15, 2024 and requires a special ticket—$34 versus the usual $27 per adult—and I beg you, go on a weekday to avoid the crowds. In a show that invites you to luxuriate, the effort to actually be able to spend some time with these paintings is worth it.