Would you be interested to go on a brief art journey that will connect you with an artwork by Felix Gonzales-Torres?

The journey starts with a question. What do we regard as a still life?

In short, in a still life we see the painter’s composition of natural and man-made objects. Often the items in the composition seem to be unrelated, like a skull next to a fruit basket, but when spending some time, one might find connections. The items are not about a live person, an animal, or a tree. Their stillness and our curiosity draw us in. Strangely enough this makes the viewer think of life: its hidden beauty and its present beauty.

One can also say that such an artwork has two functions, both dealing with perspective: composition and philosophical view towards life. Let’s look at a painting by Pieter Claesz:

We don’t see a human being, but we know that someone was present and maybe another one is expected. There are no chairs. No time to relax?

The bun, the lemon, the pie, the tablecloth/table, to name a few, show us what is outside and what is inside. This makes us see the object as a “whole”, not just the surface or only what is inside. The watch’s face is turned as if time doesn’t mean anything, but the message is relevant to any time. We don’t see the light coming through the window directly, but its reflection; the one drop on the cup turned on the spout, and the lemon peel hanging down in a spiral motion give us a feel of movement, though all is still. The knife — the cutter — is there, too.

Picasso uses the same subject matter and goes a step further in his composition of Still Life with Lemon and Glass. We hardly can recognize any of the items which makes the viewer look more closely. Maybe there in the middle is a cut lemon and farther up to your left you see a knife.

From up close this painting looks flat, even though there are many diagonal lines and curved lines. When we step back, it seems as if that flatness disappears and the gray section in the composition stands out. Did Picasso include the room in this as the objects on the table were part of the room at that time? Does this painting make you want to solve the “puzzle”? Evoking these kinds of intriguing questions must have been intentional. Does our imagination become part of the artwork?

That brings me to another question, which might seem unrelated: What is a portrait?

You most likely will say: A portrait is an artistic representation of a person (or an animal). The artist tries to capture how s/he sees the person. It is not all just about how the person really looks, but also what kind of an impression the sitter gives the artist, what the artist wants to emphasize or downplay, and what does s/he want to include or exclude.

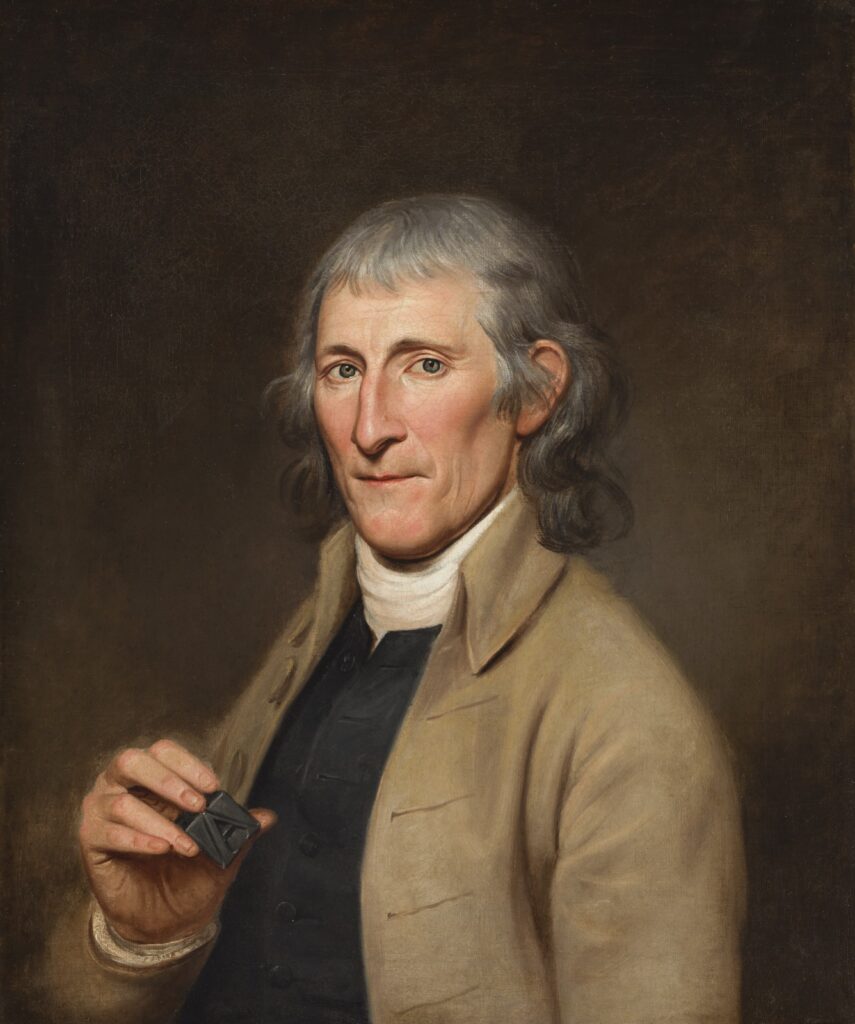

In this painting of Mr. Francis Bailey, Peale has included a printing block which the sitter had patented. Mr. Bailey had a printing business and was the official printer and publisher for the U.S. Congress. A painting such as this could have been regarded as a document.

Besides their historical value, we often like portraits as they help us memorialize a person. Just think of the Mona Lisa — the most famous painting in the world. By painting the portrait of Madam Lisa Giocondo, Leonardo Da Vinci made her be present throughout the centuries and into the future. Even such a painting might change through time without the intention of the artist. It is said that the Mona Lisa had eyebrows, but through the years the eyebrow paint has faded. In a strange way, the painting has gone through a change and did not remain still.

Portrait styles have changed throughout the centuries. Every now and then a new style comes into being. But what caused painting to change a lot was the birth of photography. Photography can in a short time capture what is real. The artists had to compete with photography.

But it also helped painters, as they could take a picture and paint from it; a far more economical and efficient way to create a portrait.

Like Picasso and Braque who came up with a new idea of representation, and thus cubism was born, another artist changed what was until almost the end of the 20th Century regarded as a portraiture. Portraits up to that time captured a special time and image, while Felix Gonzales-Torres’ portraits travel back and forth in time and can be changed as time changes the “sitter”.

The Cincinnati Art Museum, on the recommendation of Jean E. Feinberg (CAM’s then Curator of Contemporary Arts), commissioned Felix Gonzales-Torres in 1994 to do a portrait of the Cincinnati Art Museum. If you didn’t know Felix’s work and someone told you an artist created CAM’s portrait, you most likely would have thought it be a painting of the building, either outside, or inside or a combination of both.

Gonzales-Torres, who revolutionized portraiture, was born Feb 26, 1957, in Cuba. He studied art at the Universidad Puerto Rico. In 1979 he won a fellowship to study at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, NY. Gonzales-Torres died young at the age of 38, due to AIDS, in Miami, on January 9, 1996. Although his life was short, he died an accomplished artist. CAM’s portrait was created two years prior his death.

A list of major events related to the museum that made the museum’s history including the Mission and Purpose Statement, were given to Felix; Jean met him in NY, some correspondence went back and forth, the Andrea Rosen Gallery acted on behalf of Felix, and Felix presented CAM with his idea of what has made the Cincinnati Art Museum and what he believed the visitor could associate with. The portrait is called “Untitled” (Portrait of the Cincinnati Art Museum).

Felix has given CAM authority to add and remove events and dates. In the Agreement it has been stated:

“Ideal Installation: this text is to be painted directly on the wall(s) just below the point where the wall meets the ceiling, in metallic silver paint on a background color to the owner’s liking, in Trump Medieval Bold Italic typeface. If necessary, the size of the text may be altered to fit the available wall space each time this work is re-installed.”The piece was first installed on the 3rd floor in the main contemporary gallery, then in 2003 it was brought down to the main entrance lobby without any changes.

Felix was not present when the installation took place. Brushworks, a commercial sign company, was commissioned by CAM to install the piece.

As you can see in the photo above, the text is painted directly on the walls below the point where the wall meets the ceiling. Felix wanted the viewer to look up. This is the same with his other portraits of other institutions or people. Don’t we all want to put a person we love on a high place, thus giving that person our respect?

He also wanted the viewers to become more aware of their surroundings, not only paying attention to artworks at eye level or below.

Have you have seen or noticed this portrait when entering the museum? There it is to greet you. Would you have guessed that it was a portrait as it only consists of words/events and number/dates? The installation, consisting of two lines, forms a continuous circle. The reader can begin reading at any point as the events are in no chronological order. While some of the events might mean something to the reader, some may not.

I’m a docent and used to volunteer at the gift shop. One of my favorite pieces is Frank Duveneck’s Whistling Boy. When I looked at Felix’s work and saw Museum Shop 1969, Docent Class 1979 and Whistling Boy 1904 that put a smile on my face. Many other events mean something to me too, such as Berlin Wall 1961-1989, as my mother was from Berlin. Even though CAM being in Cincinnati and thousands of miles away from Berlin, that wall meant restriction of freedom. CAM is for freedom; perhaps that was one of the reasons why Felix included the Berlin Wall. Would this museum have existed in its current shape and form if there was no July 4th, 1776?

The dates make the visitor realize that this museum and the history it displays are much older than we are. Our bodies did not exist in 1886 when this museum opened its doors. When you as a visitor, enter the museum, you become part of this installation, as you become part of CAM. The museum is ‘alive’ because of its visitors. You feel the connection even more when you stand in the lobby and look up and read the events (or have someone read it to you). In order to capture the whole artwork, you must turn clockwise or counterclockwise. That may remind you of the cosmos as everything is in motion; nothing is still. Remember the spiraling lemon peel in Claesz painting? There was no life in that painting, but it was all about life. Here it is the same.