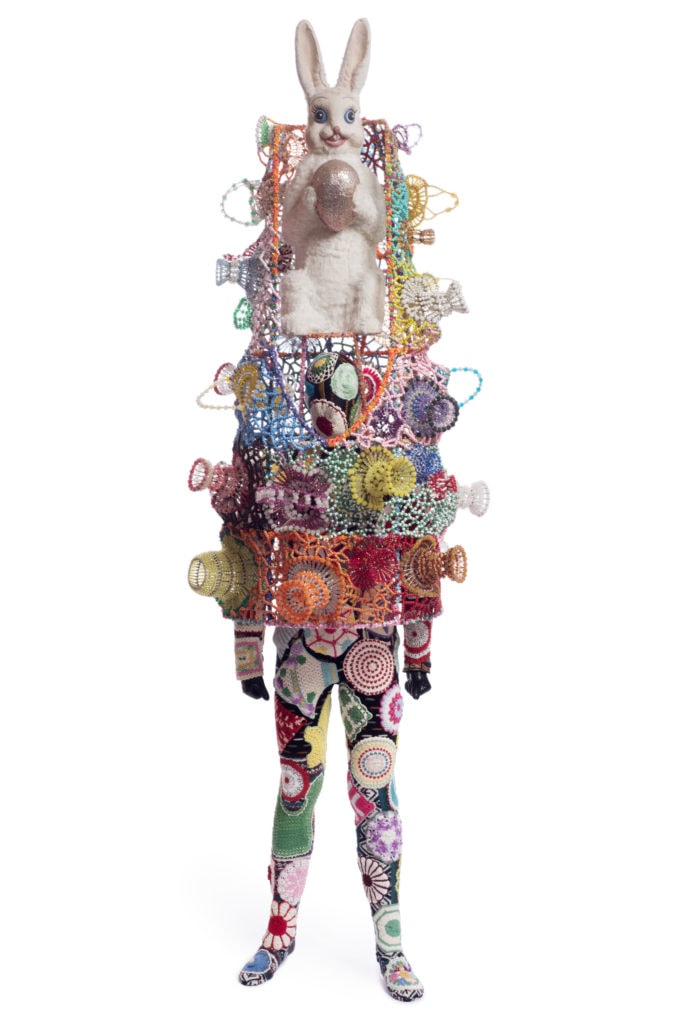

So I thought I knew Nick Cave’s work and maybe you did too. We had a chance to see one of his captivating Soundsuits in a themed exhibit at the 21C Hotel Gallery, Cincinnati several years back. Doesn’t everyone know about Nick Cave’s imaginative Soundsuits? They are bright, wild, fabric, total-body coverings, or costumes if you will, with crazy add on’s like noisemakers, doilies, stuffed bunnies and cascades of beading or twigs that make noise when the performer moves. Yes! These are in the popular imagination of those of us “who know Nick Cave.”

So then I went to the exhibit and in the captivating installation that greets viewers called Spinner Forestand are a galaxy of hundreds of twirling colored metal yard ornaments strung from the ceiling. Hundreds and hundreds. Some are modified; twirling in the center of some of the bright metal yard ornaments is the profile of a handgun. A handgun, not beads nor bunnies, to point to the tragedy of residential homicides. Nick Cave’s work is deeply political and this retrospective makes that crystal clear to me, to you, to everyone who has been dazzled and deeply moved by experiencing this career-spanning retrospective.

The beating of Rodney King in 1991 sparked the formation of Cave’s Soundsuits. As a black man, Cave could not shake the broader injustice of the treatment of black men by law enforcement. In trying to process the beating, Cave started picking up twigs in the park where he had been reflecting on the brutality toward Rodney King that was caught on video and broadcast nationwide. Somehow, as Cave said in the video at the exhibit, the twigs would cover a person and protect him/her. The rhyme “sticks and stones can break my bones” comes to mind. So he made his first Soundsuit and “Once I put it on and moved in it, I realized that was the protest-the sound it made. In order to be heard, you gotta make sound.”

From that seminal political experience in 1991 and Cave’s response by making a protective and imaginative covering, Cave uncorked his sculptural, design and costume manifestation. In some ways, Soundsuits defy easy categorization and therein lays their brilliance. Soundsuits are exhibited quietly – still – as sculpture in galleries or they are utilized/worn in live performances; they have a dual nature. Photo-documentation of his Soundsuit performances that have occurred worldwide must be awesome, all that swinging of bead strings or swaths of polyester plush, other lush and over-the-top materials, the sound that is made and the beauty of the performers who are making the art-wear sculpture come alive.

But there is more. Circling back to the beginning of his career, this retrospective examines Nick Cave’s early sculptures where he began his artistic career by utilizing what was on hand, like Mobile Construction, Trees, a large tableau of tall, found metal and wood planks that he leans against the wall. Rust, old paint and traces of lettering all become part of its beauty as Cave arranged the metal and wood planks into a tall and stately forest from the excess of our discarded materials. This piece is a harbinger of Cave’s continued and unrelenting search for meaning in society’s discards.

Certainly other artists of color mined found materials for forceful content; I think of celebrated multi-media artist Betye Saar who is 96. For her best-known work, The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972), Saar arms a Mammy caricature with a rifle and a hand grenade, rendering her as a warrior against not only the physical violence imposed on black Americans, but also the violence of derogatory stereotypes and imagery. The MCA’s exhibition curator Naomi Beckwith selected some of Cave’s heartbreaking sculptural assemblages. Nick Cave located early twentieth-century Negro kitsch (thrift shops, EBay) and these sculptures put a spotlight on the horrid racist imagery of a black man as a fool, servant and despicable being. Penny Catcher, 2009, is one of these powerful and sad images.

Mixed media including vintage coin toss, suit, shoes, and alumnium cans 74 × 23 × 14 in. Collection of Margo & Robert Roth

Penny Catcher starts with the simple wooden head of a black man with his mouth open so the carnival goers could throw pennies into his mouth. The head is encircled with the crudely carved words ‘penny catcher.’ The head looks uncomfortably yoked by the heavy wood encircling it. Nick Cave gives this man a body and proper black suit that contradicts the roughness and vulgarity of the head image. Finally, the figure has fancy oxford shoes in black and white. Is Cave saying to the viewer, “The issue of racism is black and white to me. How about you?” Finally, there are crushed pop cans under the fancy shoes. They are easy to miss especially if the sculpture is viewed frontally. The cans call attention to an inner city children’s activity of crushing empty pop cans underfoot to create noisemakers. It is possible and likely, given Cave’s deep thinking on images, symbols, sounds and words, that the child’s pop cans under the feet of a grown man calls attention to the fact that a black man was called ‘boy.’

There are a large number of works with overtly racial overtones that have gone into private or museum collections, from Akron Art Museum in Ohio to the Aukland Art Gallery in New Zealand, that have not gotten the attention and hype that Cave’s bright and astonishingly imaginative Soundsuits have gotten. It is easy to understand this. Some works are visually quite dark, such as an enormous formal black lacquered table covered with a huge collection of carved wooden African and what was called ‘ethnic’ heads and a large carved wooden bald eagle, everything shades of brown and black. This work, Untitled 2018, transports me back to the works of Leon Golub and Nancy Spero, two significant contemporary artists, both recently deceased, who set the bar for challenging, political, humanist art work. No joy and happiness in their respective oeuvres. I think of Spero’s Maypole: Take No Prisoners I saw in the grand entryway of the 52nd Biennale di Venezia in 2007. Maypole provokes critical discussion about the cyclical nature of history, war, and its victims. Severed cut paper heads strung on colored ribbons to a maypole have the same gut punch as Cave’s collection of carved heads strewn about the lacquered table. All of Cave’s work that utilize hunted down carvings of racist memorabilia and kitsch or that he cast in bronze represent the dark side of his oeuvre. In a retrospective such as this, we, the eager viewers, are gifted this entre into Cave’s whole and authentic body of work. It weighs one down, as it should.

91 × 78 × 54 1/2 in. Collection of Carol McCranie and Javier Magri. Wallwork, in collaboration with Bob Faust, 2022.

Then there is Cave’s concern for ‘man’s best friend’ featured here in three of his Rescue Series. What you see are sculptural tableaux of life-sized painted ceramic canines, again hunted down at estate sales or EBay that would have been placed in expansive foyers or on grand porches of estates. I guess they are out of vogue now but not for Cave. He has his dogs sitting majestically on vintage love seats and he created a framework around the dogs of metallic vines and floral bric a brac, thrift shop ceramic flowers and bird figurines. Massive strings of beads add glimmer and contribute to the more-is-more aesthetic. His dogs are enthroned in a bower. These works are crazy for their richness and oddness. No one else has thought to honor man’s best friend like this.

So then we come to the centrality of referencing man/men in Cave’s work and not women. Racist woodcarvings and carnie props, all male. Cast bronze male heads, arms, upraised hands. Unlike fellow Chicagoan Kerry James Marshall who paints the African-American experience in total, folks at the beauty shop and barber shop, kids coming home from school, women and men comfortable in their homes, we get none of this with Cave. This is not a criticism. Cave has staked out his territory and it is a lush, wide swath. How much this has to do with Cave being a gay man, besides being a black man? Hard to say. He simply does not land on imagery that includes men and women together. Neither does Leon Golub who I referenced earlier. Golub, married to Nancy Spero and the father of sons, focuses his energy on themes of war (men in Viet Nam, guerrillas in Central America). Mercenaries are torturing the few women Golub portrays. No happy families in either Golub’s nor Cave’s work. I bring this up because Cave talks about his very creative family and how everyone was creative and made things. The one piece in the exhibition that clearly references women is Cave’s Wall Tapestry, 2015. Here he makes a reference to “stepping out” with this huge wall piece made from women’s black, usually beaded, party dresses he nabbed from thrift shops, cut up usually along seam lines to reference the body and the crafting of garments, and made into a lush tapestry of dated, cast-off women’s party wear. Again, his use of what is typically overlooked is astonishing.

MCA

There is so much more to describe and discuss. Cave’s energy, his commitment to teaching at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, to his local community activism and all the bodies of art work in the exhibit not discussed in this article, all merit consideration. The exhibition catalog Nick Cave Forothermore is comprehensive and beautiful and should be sought out by anyone who has regard for Cave’s body of work. This retrospective, closing October 2 in Chicago, travels next to the Guggenheim in New York City opening November 18, 2022. Naomi Beckwith, who is Deputy Director and Jennifer and David Stockman Chief Curator at the Guggenheim Museum, also curates it. She states: “Nick Cave’s utopian vision and gift for magical material transformation is only matched by his generosity as a mentor, educator and activist,” said Beckwith. “I am thrilled to see that the seeds that he planted in Chicago have flourished into a citywide celebration that not only honors his inspiring work but is a gift to his adopted hometown. Equally important is that audiences at the Guggenheim New York will also have the opportunity to experience a fulsome view of Nick’s artistic and life practice. Nick is an artist who allows all his audiences to celebrate, mourn, and learn with and from each other; a kind of social healing that is so necessary as the world contends with continued physical and political isolation.”

All photographs except Image 5, Soundsuits are by author. Image 5, MCA, Chicago.