Cincinnati Art Museum through Nov. 11, 2023

Ohio Voices, an exhibition in the Cincinnati Art Museum’s small Gallery 213, currently displays prints and drawings with powerful messages. Tucked between larger galleries, many people pass it by, but if you do, it would be a real loss. Print Curator Kristin Spangenberg has selected a set of artworks that moved me with their beauty, innovation and sometimes pain. Ohio Voices recognizes contributions of contemporary Ohio artists.

The exhibit celebrates the 30th anniversary of the Donald P. Sowell Endowment Committee, a museum affiliate group established in tribute to Donald P. Sowell (1929-1989), an important Cincinnati artist and art educator. Mr. Sowell was the first African-American art teacher in the Cincinnati Public Schools and an art supervisor for twenty years. The Sowell Committee promotes greater interaction and involvement between the African American community and the museum, by sponsoring internships, exhibitions, and library collections, advancing the museum’s mission to diverse audiences. Many of the prints in the exhibit were purchased with funds from the Sowell Committee.

Begin your exploration of the exhibit at the left of the hallway leading to Galleries 231 and 232. The artists in this section were all involved with the Karamu House in Cleveland during the Great Depression. Young artists and performers found hope in this center for the arts that emphasized interracial and cross-cultural understanding. Founded in 1915, today it continues to provide professional theater and arts education for all people while honoring the Black experience. There are graphically strong prints by Elmer W. Brown, Hughie Lee-Smith, Fred Carlo, William Elijah Smith and Charles Sallée, Jr. many of whom worked during the Great Depression for the Federal Works Progress Administration and later became teachers.

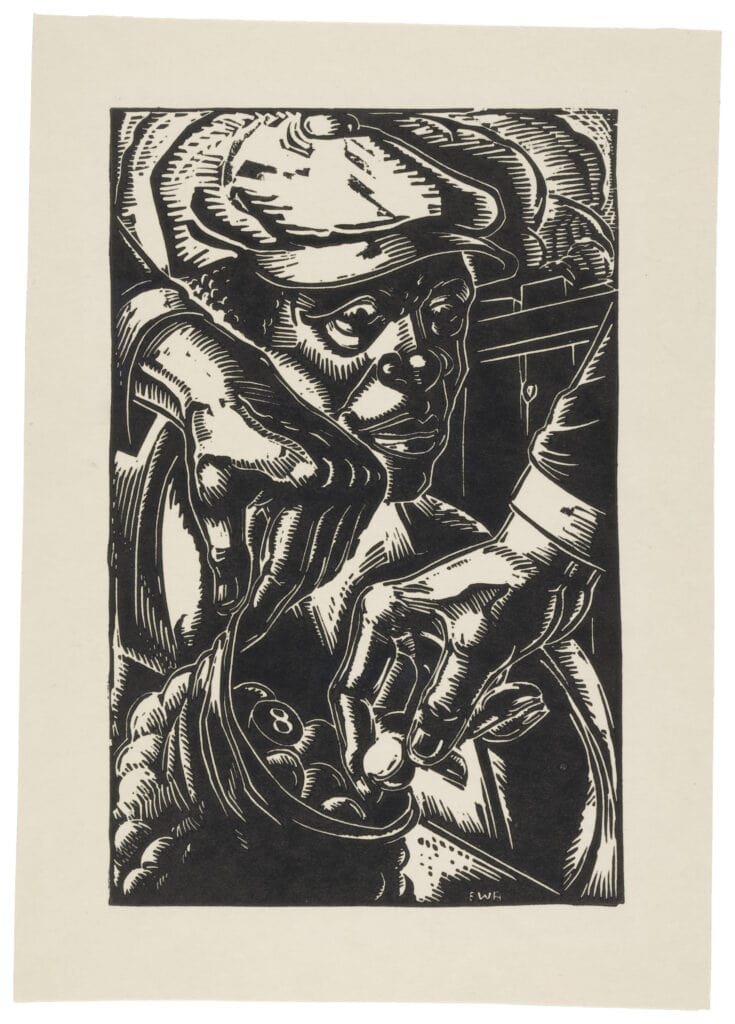

Numbers Pulling, circa 1938-41

Linoleum cut, Museum Purchase: Art Acquisition by Minority Arts Fund, Millard F. Rogers, Jr.

Gift of Art Fund and The Albert P. Strietmann Collection, 1995.74

The strong black and white contrasts of Numbers Pulling by Elmer W. Brown will catch your eye. The face is enigmatic, framed by strong hands, one holding the bag and the other pulling a number, perhaps hoping to win big. It is typical of Brown’s early work, documenting the lives of African-American men during the late 1930s and early 1940s. In 1953 Brown began an eighteen year career as the first African-American illustrator for American Greetings. He was a successful painter, educator, stage designer and muralist who also worked in ceramics and enameling.

Entrance to Eden Park, 1958

Watercolor over traces of blue crayon, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Lester Hunter, 1998.118cam_1998.118

When you cross the hallway, this large bright watercolor will be the first artwork that you’ll see. Mr. Sowell’s control of the washes celebrating the cherry blossoms, and the calligraphic lines of the tree trunks is outstanding. The painting is large and commanding. He celebrates the beauty of nature in one of Cincinnati’s most beloved parks. From an early age, Sowell knew that he wanted to be an artist and an art teacher. He studied at the Art Academy of Cincinnati and received an MA from Xavier University.

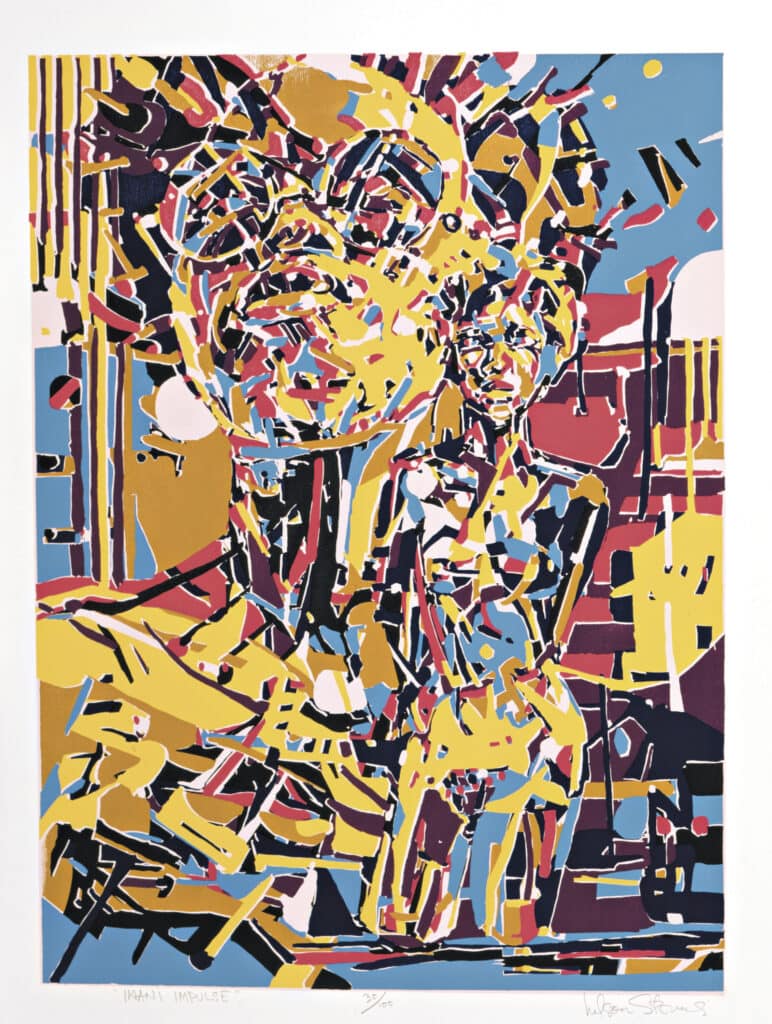

Imani Impulse, 1974

Color screen print, Gift of Alice Bimel, 1974.379

Bursting with color and energy, Imani Impulse will take you back to the 1960s and 1970s. In this screen print, Imani exudes confidence and swagger. Nelson Stevens said, “I deal with the physiognomy of the soul of Black folks.” In 1969 after earning an MFA, he joined AfriCobra (African Community of Bad Relevant Artists), a collective based in Chicago that, rather than political revolt, fostered solidarity and self-confidence in the African diaspora. Stevens taught at Karamu House, Northern Illinois University and the University of Massachusetts. He believed that the creation of art was “for the sake of people” rather than “for art’s sake.”

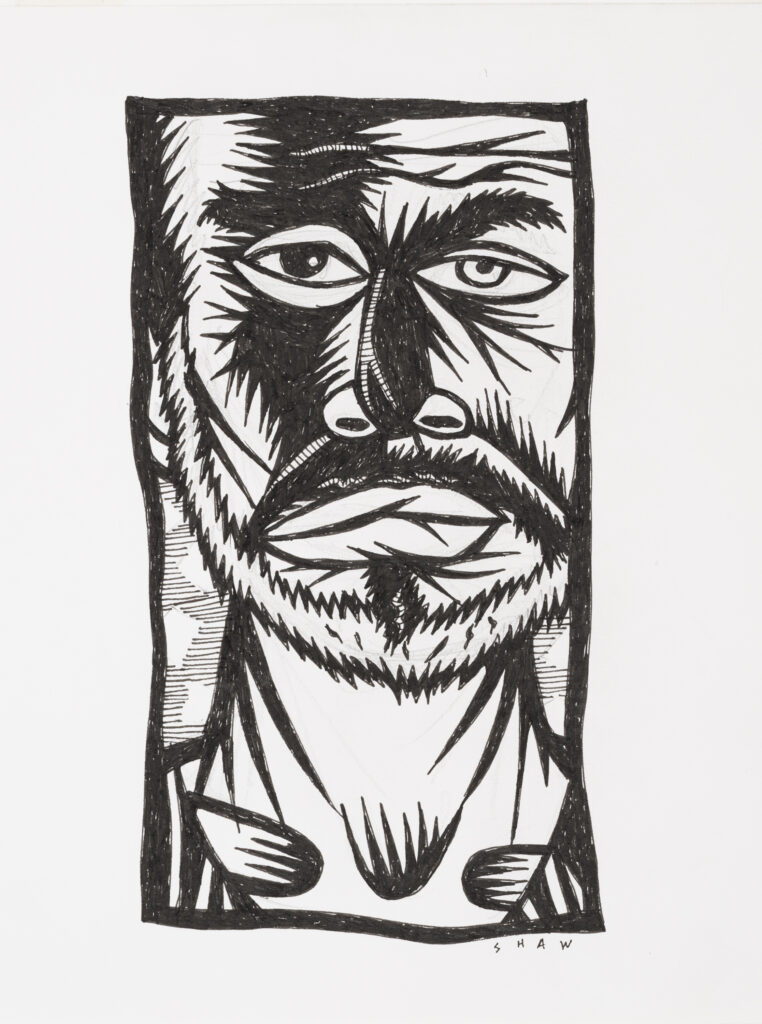

Study for Today I am No One, What about 2 Hours from Now

Pen and black ink over traces of pencil, Museum Purchase with funds provided by the Donald P.

Sowell Art Purchase Account, 2015.65

Gallery 213 is a series of shallow alcoves. The entire next alcove is dedicated to the Cincinnati painter, printmaker, draughtsman and graphic designer, Thom Shaw. He created unrestrained, in-your face-recordings of the state of affairs in inner-city America. The study for Today I Am No One confronts you with its directness. The museum owns the finished painting which has been the focus of many deep conversations when it’s been part of one of my tours. The woodcut Felicia is pure pain. The portrait could be of one of the parents I worked with at Taft High School. Her daughter disappeared. Weeks later she was found in a crack house. Her efforts to help her daughter seemed to be hopeless. Be prepared to be moved.

Biker Couple, 2012

Unique color photo screen print, Museum Purchase with funds provided by the Sowell

Committee, 2013.16

Years ago, Hammonds was invited to participate in an exhibition called Beyond Emancipation. It prompted him to innovate, to think about what free could mean, who lives beyond the rules. He was intrigued by the outlaw biker culture, people who needed to form an identity in opposition to mainstream society. Hammonds said that this work combines a photo of a biker couple from the seventies, “in their best modern savage wear with a wallpaper pattern that could be found in a well-appointed home. I really like how the two images abstracted each other.”

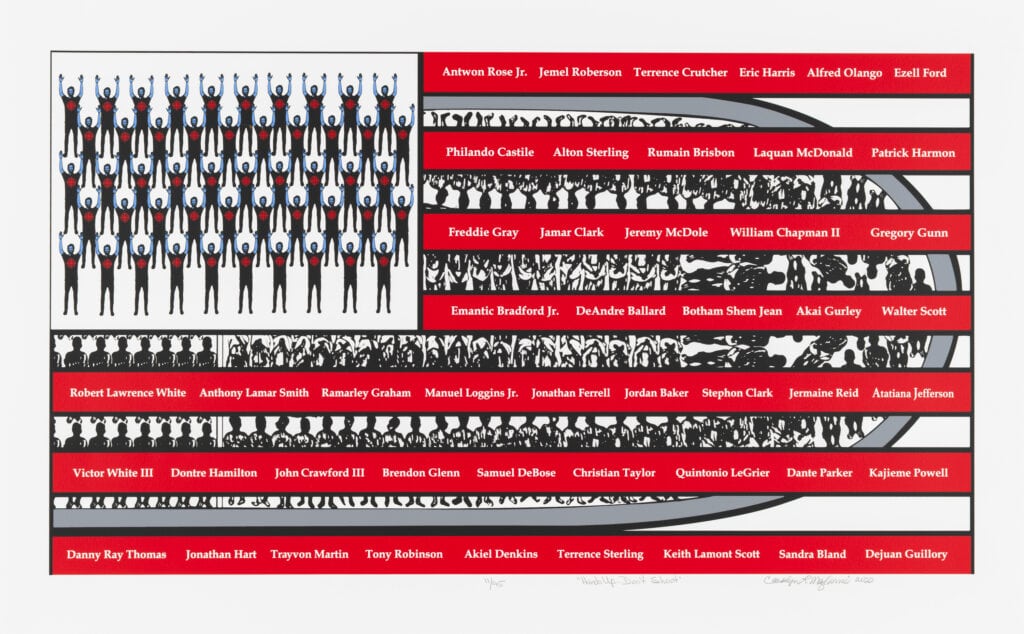

Hands Up…Don’t Shoot, 2020

Color screen print, Museum Purchase: Anonymous Gift in memory of Helen Pernice, 2021.7

Originally a quilt artist, Mazloomi expanded her art beyond geometric patterns to social justice issues. Look closely and you’ll see the names of Black people killed by police, including Samuel Dubois fatally shot in Cincinnati in 2015 during a traffic stop for a missing license plate. Mazloomi states, “I keep a list of names of such victims. They are the stripes on the flag because they were American citizens and the flag is the symbol of the nation.” The stars, fifty Black bodies with their hands up, represent the states where African Americans have been killed by police. She now creates prints from her quilts so that her designs are available to a broader audience.

The Ohio Voices exhibit ends with a superb drawing by Gee Horton, Black on Both Sides from his Coming of Age series that explores the complexities of African American adolescence. His subject is his nephew who is in the most formative years of his life. Through the portrait, Horton reflects on his own early years as a way to heal personal trauma. It took him four weeks to complete the portrait. “I use charcoal because it captures the depth of the color black,” Horton explains.

The Cincinnati Art Museum offers a wide range of programs supporting its exhibits. On November 8, Curator Spangenberg hosted an excellent presentation by four of the artists in Ohio Voices: Kevin Harris, Ellen Price, Carolyn Mazloomi and Gee Horton. In the question and answer session, Carolyn Mazloomi shared that she focuses on family, the status of men and social justice issues. She said that her artworks often provoke controversy that results in “so much hate mail. I know I’ve touched a nerve. I’ve done my job.”

You can sign up for a weekly e-newsletter to learn about more great CAM programs for adults and families: https://tracking.wordfly.com/join/CincinnatiArtMuseum/