Henri Matisse in The Red Studio

Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911) famously depicts the artist’s workspace in the Parisian suburb of Issy-les-Moulineaux, the studio awash in an ocean of Venetian red and collapsed along a single plane. I had the pleasure to view this work in MoMA’s current exhibition, “Matisse: The Red Studio” (running through September 10, 2022). The exhibition is a tenacious demonstration of prudent curatorship and object research, reuniting ten of the eleven objects that were together in Matisse’s studio at the time The Red Studio was made, including Le Luxe II (1707-08) and lesser-known works like Corsica and The Old Mill (1898). The exhibition also features objects only recently rediscovered. That first gallery room illuminates how Matisse treated his private sanctum as a kind of self-portrait, with each object standing in for some period of Matisse’s past, aesthetic taste, or aspirations. The second gallery room traces the trajectory of The Red Studio (1911) after it departed from Matisse’s hands, with the painting spending decades in the wilderness before settling down as one of MoMA’s august darlings. The paintings making up the show have been gifted to MoMA on behalf of the late, great Pierre Matisse, the son of Henri Matisse’s son who famously ran The Pierre Matisse Gallery where Pierre introduced manifold avant-garde artists in Europe to American audiences (including Miró, Chagall, Giacometti, Debuffet, and many others) from 1931 to his death in 1989. The exhibition also features a number of important, lesser-known works that will undoubtedly entrance Matisse enthusiasts. One such “minor” painting is Bathers (1907), which I will shortly return to.

Sauntering through the exhibition, my partner, Abigail, and I were enchanted by the curatorial puzzle that unspooled: spotting objects and paintings featured in The Red Studio (1911), we playfully identified them with those comprising the exhibition. This whimsical, childlike activity that the artwork, in conjunction with the curatorial vision of Ann Tempkin (MoMA) and Dorthe Aagesen (SMK, the National Gallery of Denmark), stimulates provides for a wistful museum-going experience. Some genuine curiosities abound, including a tucked away headless terracotta figure that Abigail pointed out—an artifact that had long been tucked in Jean Matisse’s private collection (Jean being another of Henri Matisse’s sons). The curatorial gambit arguably extends Henri Matisse’s dream of proffering paintings that would appeal to broad strokes of the population; an art practice, to quote Henri Matisse, “of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject-matter, an art which could be for every mental worker, for the businessman as well as the man of letters, for example, a soothing, calming influence on the mind, something like a good armchair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.”

Thus, if nothing else, this exhibition thus prods viewers into the role of a sleuthing detective. The works exhibited are, of course, masterful: Matisse’s vermillion fauvism needs no introduction and viewing his prismatic use of variegated color with masterful paintings like “Corsica, the Old Mill” (1898) and “Le luxe (II)” (1907) is an absolute pleasure. It is, indeed, testament to Matisse’s singular vim and comprehensive virtuosity with managing color palettes that both the eponymous exhibition and The Red Studio (1911) painting bring to bear. Quotidian objects are flattened and made fantastical. But at this point, I would like to draw our attention towards Bathers (1907). For Matisse’s Bathers (1907) is a unique example of the post-impressionist nude study, occupying an entirely distinct terrain from Matisse’s compatriots, such as the late-career Renoir and his Modèle allongé (1906), where bleary, indistinct strokes of paint cascade both furniture and the depicted blush-cheeked nude into a fumed haze.

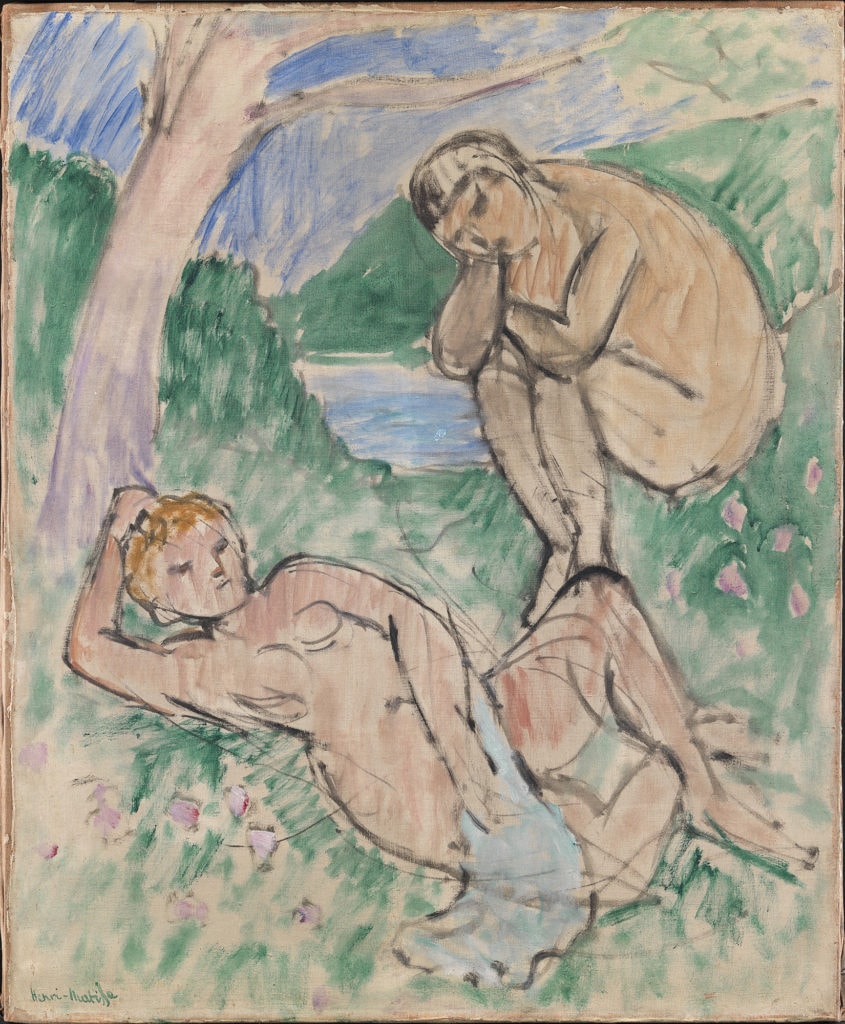

Matisse’s Bathers is rich and imbued with a subtle, but critically important, art historical genealogy that not only arrives at the decisive moment between impressionism and post-impressionism but also speaks to the trajectory of early twentieth century modernism to come. In Matisse’s Bathers, two pallid, unclothed women with tussled hair—auburn and chestnut brown, respectively—are presented, hunched in verdant hills adorned with rosy, coral petals by their feet. Strokes of blush pink kisses the shoulders and forearm of the splayed bather on the right, who uses a light, washed-teal piece of garb to robe her groin. The hunched bather on the right peers downwards. To their upper left, we see a body of cloudy azure water—perhaps a river or lake—overcast by the plum-purple heavens. The bathers are outlined in a dark, bold contour while hasty, sketch-like strokes of paint swing and unwind into a complexion that is adjacent to, but still distinct from, that which might be termed properly impressionist. This painting squarely orients Matisse as a post-impressionist and not an impressionist; while representational figurative icons are retained, indices like the eyes, mouth, nose and eyebrows of the bathers are reduced into single strokes. Color is given priority and the base of the tree enjoys an almost mulberry-wine color that compliments the flora on the plain upon which the bathers recline and lounge. It is a placid scene but the composition, although it is a painting, is almost sketch-like.

Matisse’s Bathers seemingly directly relates to Cézanne’s 1879-1882 Three Bathers (Trois Baigneuses). Cézanne had a profound influence over Matisse, as the latter greatly valued the former’s work. The story goes that in 1899, despite having scant funds, Matisse managed to purchase Cezanne’s Three Bathers (and subsequently went on to purchase six Cézanne watercolors in 1908), as he was so taken by the painting. In Matisse’s 1907 painting, we see him adopt Cézanne’s strategy of leaving specific areas of the canvas unpainted, using negative space and therein taking up an aesthetic view that is directly poised contra the phenomenological purview of perception that had dominated impressionism. For where impressionism proper emphasized luminosity, Matisse’s concern is with brandishing minimal strokes, each sparing stroke culling absolute necessity. Where the great impressionists departed from veridical perception, the bleary-eyed, speckled strokes of a mid-career Renoir or Monet never left room for open space the likes of Matisse and Cézanne.

While Cezanne inaugurated this practice of strategic negative space, it is in Matisse where we see this practice dovetail with a penchant to derive strong, bold outlines of the depicted figures. In bringing these two modalities together, Matisse directs a shift away from the natural world altogether: nowhere, not even in hallucination or myopia-bedaubed visual perception do such bold outlines or unfinished pockets ever appear. The natural world outpouched, this work speaks to not only a departure but a clean break from the world of mirror images. Indeed, this reverberates with Arthur Danto’s claim that “[w]ith the advent of Modernism, art backed away from mirror images” (Danto 2013, xi). What Matisse’s painting instead centers is the wilderness, making no arbitrary delineation between the realm of nature and that of mankind. This preoccupation with this truth of wilderness echoes the professed Fauvist namesake, instated during the 1905 Autumn Salon held in the Grand Palais in Paris, where critic Louis Vauxcelles described the displayed works as “a Donatello surrounded by wild beasts [Fauves]”, thereby introducing the term into consequent art historical lexicon.

In his essay, “Freedom from Nature? Post-Hegelian Reflections on the End(s) of Art”, J. M. Bernstein examines, a la Adorno and Hegel, the role between natural beauty, natural scenography, and modernist art. Here, he makes a telling reference to Henri Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911) as revealing that which so-called “modern art” is preoccupied with. I believe that what Bernstein detects in The Red Studio, however, is equally pertinent in Matisse’s Bathers. If Matisse’s modernism reverberates with the apothegm that modernist images are not (veridical) images of anything out in the empirical world, then the following query comes to the fore: what is the relationship between natural beauty and the beauty that the Fauvist-cum-Modernist project is preoccupied with? It is certainly not an identity relationship, where the former maps on to the latter. J.M. Bernstein, in his essay “Freedom from Nature? Post-Hegelian Reflections on the End(s) of Art” (2007), muses on a detectable turn in modernist aesthetics in this era, noting that:

the nature that finds its way into painting, on which painting depends, and which is what is glimpsed in natural beauty […] is a nature that is no longer an object of scientific knowledge or practical labor, which prima facie may be assumed to exhaust what nature may be. What else of nature there is, art alone systematically interrogates. Hence, if art depends on this impossible nature for its objectivity, it is equally true that only in the context of art is nature as appearance salvaged. (236)

This is, in my opinion, an apt rendering of the context of nature that Matisse’s Bathers is imbricated in. The “what else” of nature is of a piece with phenomenological truth and not representational truth that is reducible to empirical units. Hence, Matisse disrobes the empirical world not only of its familiarity, but of its essence altogether—consequently, we have these lingering modules of negative space, these gaps in the natural world. This is not to cast Matisse as a lone figure unhusking dead representational spandrels to unfurl an altogether novel mode of meaning-making qua art. On the contrary, Matisse is but part of a movement broadly interested in how we view the aesthetic act of representing to the natural world of representeds. What makes Matisse’s Bathers particularly unique, however, is how the work ushers in an agreement between what previously subsisted as a great dichotomy: the opposition between line and color, i.e., the debate of (the influence of) Ingres versus Delacroix. Matisse’s Bathers by no means rings in the denouement of this project but spotlights an approach that future artists would implore via abstraction, only to then further open art history to welcome non-objective abstraction. MoMA’s “The Red Studio” historically situates this moment of breakage, and aptly so.