The morning of July 15th I woke to the familiar smell of smoke from burnt wood (familiar because my own, wooden house had burned less than ten years earlier – for years that smell set off alarm bells in my brain). There was a fire burning near Arles, probably caused by personal fireworks set off the night before.

As it was my last full day in the south I decided to spend it somewhere other than Arles and visit some of the “Grand Arles Express” satellite exhibitions in neighboring towns and cities. I picked Aix-en-Provence because there were two exhibition listed there: one billed as examining the way photography communicates visually, the photographs supplied by Paris’ Maison European de la Photographie, and the other, a short walk away at the Musée Granet, a collaborative exhibition featuring Bernard Plossu, probably France’s most celebrated photographer. I was looking forward to both.

The satellite exhibition visits were a good idea but getting there was going to entail another bus adventure. I had already tried and failed to achieve this trip two days earlier. At least I knew now approximately from where the bus was supposed to leave, and the bus number (it was my home address as a boy). The actual bus was missing its numerical identification, but as it was the only bus whose driver boarded two minutes before the scheduled departure time it proved to be the correct bus. The driver automatically charged me the “senior” price of 1 Euro fifty, an unexpected savings. Of course, as the bus had been sitting in the 98º sun up to that moment, it was like boarding an oven. Despite the boarding in time the bus left Arles nine minutes late and I had just ten minutes to change busses at Salon-de-Provence, but my friendly driver pointed out the bus for Aix already loading as we arrived in Salon, so I just made it. This ride to Aix was considerably shorter than the segment to Salon, so I was a bit surprised when the second driver asked for 6 Euros fifty, more than four times than the longer trip. Turns out each different bus company decides its own rates; also the second bus company gives the senior rate only if you have a special, government issued travel card, which left me with just a Euro cash until I could find an ATM in Aix.

My first visit was to Aix’s Espace Cultural on the broad, tree shaded and very walkable Cour Mirabeau. My phone was not pulling up a map but I had memorized the walking routes before setting out. When I arrived at the door, the large iron gate in front was shut. I couldn’t believe it; how the hell did I not find out the exhibition was closed today? In frustration I tugged at the bars, at which point the gate heavily swung open to permit entry. Whew. The trip would not be a wash.

The exhibition, titled The Silent Language, turned out to be only portrait photography, but a reasonably loose translation of the concept by many familiar photographers, some old friends, with beautiful prints, well presented as mini-solo exhibitions. The first encountered were half-a dozen of Emmett Gowin’s early photographs of his wife Edith and her family – photographs I have loved since first seeing them in 1971 when Linda Conner brought a portfolio of them to San Francisco with her to begin her teaching career. Nearby were Harry Callahan’s portraits of his wife Eleanor. There also were Cindy Sherman’s self-enactments and Nan Golden’s portraits of a Parisian couple during a year in which one succumbed to AIDS. Other American photographers included Diane Arbus, Robert Mapplethorpe, Henry Wessel and Lexington’s Ralph Eugene Meatyard, along with an equal number of Europeans, including Rineke Dijkstra, Bertien Van Manen, Dolorès Marat, Helmut Newton, Martin Parr, and Bettina Rheims – a veritable smorgasbord of great photographers’ interesting work.

The photos were lit with projection lighting, which isolates just the framed work rather than also illuminating the surrounding wall. It’s dramatic and effective, but for my taste overly so, making the photographs seem almost projections themselves. Still, to be out of the bright Provençal sun the cool darkened, spot-lit space was welcome.

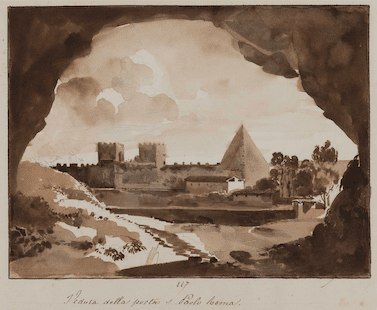

A ten minute walk away, the Musée Granet had created an exhibition titled Italia Discreta pairing a hundred or so of its 19th century Italian paintings and prints with Bernard Plossu’s photographs from Italy over the past 50 years. I exhibited Plossu’s work at the gallery I directed in Wales in the early 1980s and again in Cincinnati in 2015. We’ve known each other since the 1970s, friends nearly since our youths. Bernard’s photographic output and the number of exhibitions and publication he has amassed amaze me (there are probably something like a hundred books dedicated to his work). Interesting and instructive as the exhibition was, the lighting was generalized and fell off in the corners, as though not much thought had been given to it.

COURTESY OF THE GRANET MUSEUM, AIX-EN-PROVENCE.

Between the two art spaces, I passed another called l’Hôtel de Caumont, an exquisite 18th century mansion housing temporary exhibitions, and stopped in. Installed was an impressive Raoul Dufy retrospective of more than 90 paintings, most loaned by the Museum of Modern Art of Paris. In addition to increasing my appreciation of Dufy (the impression of whose work I had formed largely from his more decorative, mid-20th century pieces), the installation was a clinic in lighting artwork,. It combining an even, generalized lighting with a barely noticeable projection spot on each painting. The combination enabled each work to glow just slightly in relation to its surroundings, as though via its own radiance – as close to perfect lighting as I’ve ever encountered and a practice I doubtless shall recommend to others.

I left Arles for Paris the following day on Arles’ lone direct TGV (high speed train). It was delayed reaching Arles for an hour due to a fire west of town, and forced to stop again two more times en route. At one point we just crawled along for nearly an hour through blackened, burned out landscapes, in some places the ground still smoking (so saddening and mesmerizing I completely forgot to take photographs). The speed was kept slow to avoid sparks from the wheels on the rails, which easily ignite the dry grass near the tracks and the fire spreads rapidly. In addition to the temperatures this was also France’s driest July on record.

Paris too was experiencing extreme heat, around 40ºC (105ºF) reaching 41º before I departed. Normally I would walk a lot to visit exhibitions and chose from my list of vegan restaurants, of which Paris has many. But this summer I traveled underground (by metro) when I did venture out and often ate prepackaged meals in my hotel room (to begin writing this report). Still, there were a few exhibitions in Paris I was determined to see.

The first of these was at the Maison European de la Photographie (European House of Photography) in the artsy/gay Marais district. The MEP presents three main exhibitions annually plus exhibitions devoted to emerging artists. Their curatorial team regularly creates excellent and interesting exhibitions and I’d already heard about the ones there this summer: a group exhibition titled Love Songs: Photography and Intimacy and a solo exhibition Another Love Story.

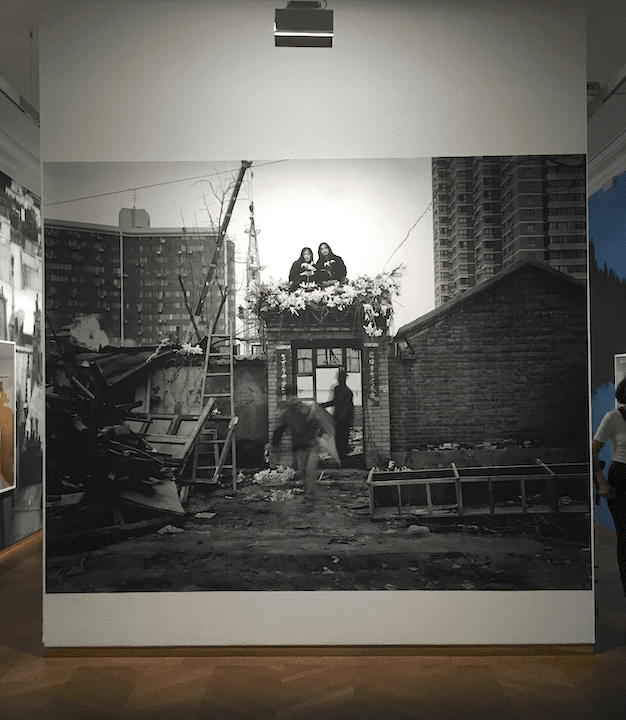

Love Songs was announced as proposing “a completely new vision of the history of photography through the prism of intimate relationships between lovers” (so very French this hot summer). The exhibition was “conceived and organized like a musical compilation offered to a lover, with Side A, the first half of the show, made up of series from 1950 – 90 and Side B, the second half, 1990 to now.” It moved from the first days of an affair, through marriages, honeymoons, domestic bliss. the pain of separation, even to the last days shared between lovers. 14 photographers’ works were featured (two working as couples), including Nobuyoshi Araki, Nan Goldin, René Groebli, Emmet Gowin, Larry Clark, Sally Mann, Leigh Ledare, Hervé Guibert, Alix Cléo Roubaud, JH Engström & Margot Wallard, RongRong & inri, Lin Zhipeng (aka No 223), Hideka Tonomura and Collier Schorr. It was a lot to take in. I’d have preferred to view it with a lover but, alas, was on my own.

(PHOTO BY AUTHOR)

(PHOTO BY AUTHOR)

The other MEP exhibition, Another Love Story, was created in response to an invitation to the 30 year-old French-Dominican photographer Karla Hiraldo Voleau to show her work during Love Songs. This was her first solo exhibition in France, although she’d been shortlisted for the 2019 Aperture First Book Award for her book Hola Mi Amol, exploring the myth of Latin-American virility, and more recently had worn a mustache and facial prosthetics to visibly become a man for a week while an assistant followed and photographed her around Laussaune, Switzerland (her current home) for her exhibition Becoming a Man in Public.

Initially, her MEP project was conceived as a romantic tribute to love, describing how the artist and a previous partner found their way back to each other after a four-year separation. But the project was radically reimagined when she discovered that the man was maintaining a double life with another woman, leading Voleau to telephone what she thought had been his ex-girlfriend. A text read “It was one year after we got back together, and I wanted to ask her why she was still in contact with my boyfriend. She replied, ‘Well, he’s my boyfriend too. I live with him. I’ve been his girlfriend for four years. We are trying to have a baby.’ We realized we were each other’s ‘other woman’. In a seven-minute conversation, we found out that [the man] was a master manipulator and someone with deep troubles.” It’s a disturbing reconstruction in photographs and texts of the last months of Voleau’s relationship, re-appropriating the story by hiring a look-alike actor to stand-in for the deceitful companion, attempting to identically reproduce photographs they’d taken of each other when together.

AT THE MAISON EUROPEAN DE LA PHOTOGRAPHIE

There are plenty of places in Paris to look for interesting photography exhibitions, one in particular is the Jeu de Paume, the former Impressionist paintings museum now the Galerie Nationale de l’Image. This summer it was showing three bodies of work connected to film and video: Marine Hugonnier’s Cinema in the Guts, 16mm films “seek(ing) the possibility of a non-gendered gaze and a convergence between human and non-human”; Jean Painlevé’s Feet in the Water reprising the work of the scientific documentary filmmaker whose work in the ’30s crossed the boundary between science and art to be taken up by the surrealists and others; and Reversing the Eye: Arte Povera and Beyond, 1960-75 showcasing the work of this Italian Avant-garde group. The latter exhibition was jointly presented (for the first time) with another must-visit venue for photography exhibitions in Paris, LE BAL, a bookstore, café and gallery space in the north of Paris (not so unlike Iris Bookcafé and Gallery in Cincinnati, but larger with segregated spaces), which can usually be counted on for excellent exhibitions. Unfortunately, I was unable to get to it’s portion of the collaboration with the Jeu de Plume, which I expect I’d have enjoyed the most of the four exhibitions.

Another venue which usually has something of interest is the Centre Pompidou (a.k.a. Beauborg), one of the most recognizable buildings in Paris (after the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe), due to its ‘inside-out’ architecture/construction revealing color-coded structural, mechanical and circulation systems exposed on the exterior of the building. On two of its various levels is the the National Museum of Modern Art, where I was heading to see a huge exhibition: the first overview in France of Germany’s Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) movement of the 1920s, which in addition to painting, architecture, design, film, theatre, literature and music, included a comprehensive exhibition of the work of photographer August Sander, around which the larger exhibition was built (an “exhibition in the exhibition”).

Sander’s extensive masterwork, People of the 20th Century, attempted to document the entirety of German society and his sociological categories were used as a framework for the uber-exhibition. It really was extraordinary, but It wore me out such that after a quick visit to the Pompidou’s photography gallery in the basement (a retrospective by Jochen Lempert, whose Field Guide exhibition was presented at the Cincinnati Art Museum in 2016), I failed to discover another exhibition in the building, Le Reste est Ombre (The Rest is Shadow), creating a conversation among the works of three Portuguese artists: a filmmaker, a sculptor and a photographer. This was particularly disappointing to me because the photographer, Paolo Nozolino, was my student in London at the beginning of his career and became Portugal’s most acclaimed photographer (“one of the central figures of contemporary photography” states the release).

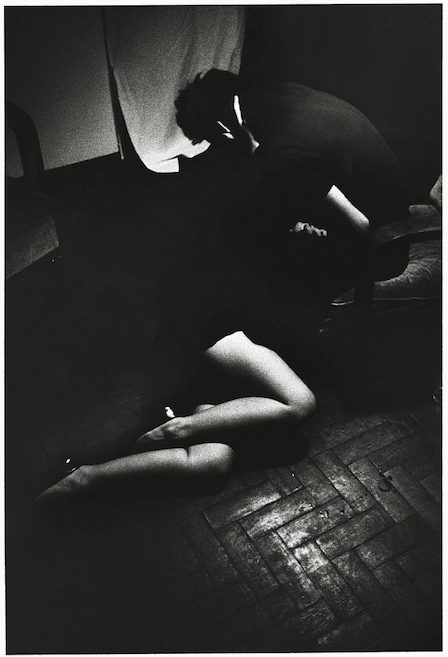

I learned of Le Reste est Ombre only when back in Cincinnati, writing this report. The Pompidou publicity calls it “an immersive mental journey,” to which, knowing Paolo’s work, I would add “emotional” as well. Paolo has always loved the dark, the shadows, what cannot be seen, and what emerges from them in light. I couldn’t discover all the work he showed at Pompidou, but here’s an example of his way of seeing, which may well have been included.

Happily, I did manage to connect with Danielle Voirin, the American photographer (from Indiana) now living in a village an hour south of Paris with her French husband and daughter Ever, who had her first solo exhibition at Iris in Cincinnati back in 2010 (FEMME).

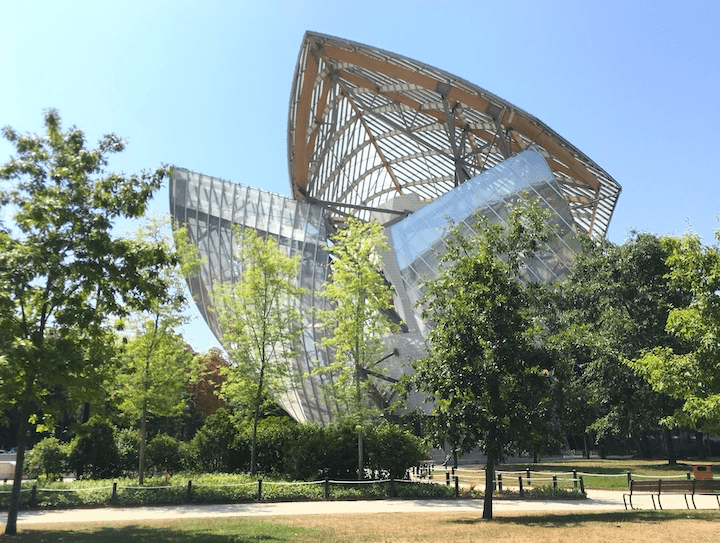

The morning before meeting Dannie, I decided to visit another signature Frank Gehry museum building I’d wanted to see for some time, his 2014 Fondation Louis Vuitton in the Bois de Boulogne park on the western edge of Paris. The project’s commissioner was inspired by Gehry’s earlier titanium-clad Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. Gehry also took inspiration from 19th century French glass and garden architecture. Then he pushed the envelope – an envelope of curved glass (now often referred to as “the sails”) around an undulating solid form of white fiber-reinforced concrete (“the iceberg”) all made possible via Gehry Technologies’ unique software program which enables scanning whatever model Gehry’s team can come up with and translating it into architectural projection stats for construction. A special furnace had to be created to meet the requirements imposed by Gehry’s design for the curving glass panels. A massive wood substructure is visible supporting the transparent sails, perhaps more organically referencing the metal superstructure of the Centre Pompidou, and one-upping the 2006 Shigeru Ban designed Centre Pompidou Metz in the east of France.

The day before, I had walked past the Louis Vuitton store near the Jeu de Paume and stopped in to ask about the Foundation. An imposingly tall, beautiful Russian woman met me at the door to say they were closing; I asked only whether she or anyone knew what exhibitions were currently on at the Foundation. At least five different people discussed this, several consulted their phones. Finally the word was delivered to me that there currently were no exhibitions installed at the Foundation. As I principally wanted to see the building, I headed out there anyway.

There were two major exhibitions installed: an Ann Baldassari curated survey (130 pieces) of the work of Simon Hantaï on the centenary of his birth, and a group exhibition titled La Couleur en fugue (Fugues in Color) which filled five galleries with work by five internationally-renowned artists of differing origins and generations, including two works created especially for Fondation Louis Vuitton.

Installed at the entrance to Fugues was an historic array of Sam Gilliam’s Drapes from the late 1960s and early 1970s, shown for the first time in France – huge colored canvases, hanging freely in space, which marked a major turning point in the history of American abstract art. Somewhat in dialogue with Drapes were Steven Parrino’s Misshaped Canvases from the late 1990s, scrunched up, mostly monochromatic canvases, placed on the floor, or wall-mounted (resembling unused condoms), challenging the image or object-ness of a painting. They also carried some challenging titles for the international audience, like 1996’s Blob (Fuckheadbubblegum). Both artists’ work seemed to have been selected to reference the architecture of the building.

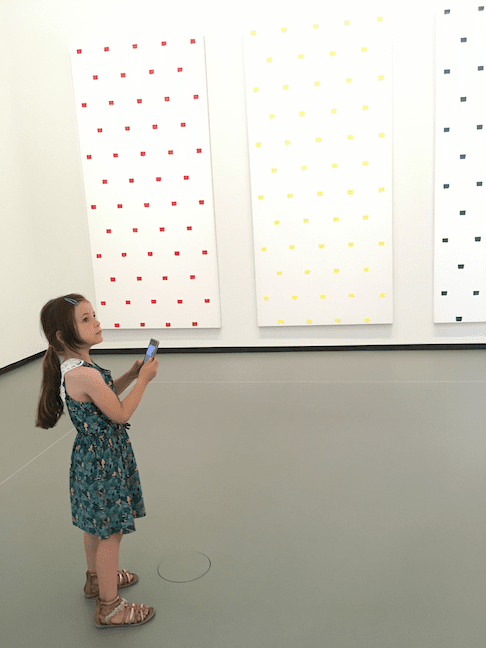

These two Americans were followed by a Swiss artist, Niele Toroni, whose repetitive yet almost imperceptively varied brush “stamps” on a variety of mediums spoke of a decidedly different cultural mentality, perhaps also referencing the 3,600 panels that form the building’s twelve sails or the 19,000 panels of white Ductal (fibre-reinforced concrete) that form the skin.

EMPREINTES DE PINCEAU Nº 50 RÉPÉTÉS A INTERVALLES RÉGULIERS DE 30 MM, 1967

(PHOTO BY AUTHOR)

The last two artists seem to have received carte blanche to have their way with the spaces. One was Canadian Megan Rooney’s With Sun (2022), combining painting with performance art, applying her paint to the walls live, using a variety of tools to produce a non-figurative “immersive realm of [mostly yellow and orange] coloured vibrations.” While the 55-year old German artist Katharina Grosse covered wall and floor in swirling color, punctuated by a rising overlapping triangular edifice, in a work titled Splinter (2022). Both galleries had large skylights adding illuminating and opening the works.

© ADAGP, PARIS, 2022, PHOTO © FONDATION LOUIS VUITTON / MARC DAMAGE

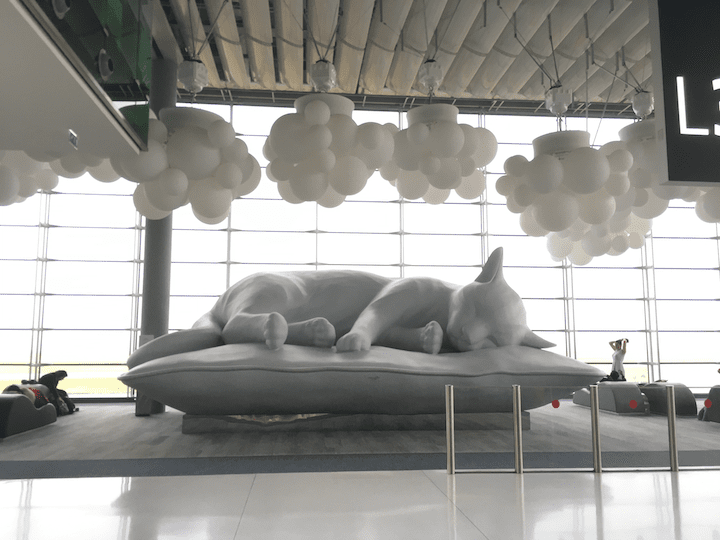

I wasn’t feeling so well my last night in Paris so I took a Covid-19 test, which was negative. But by the time I reached Charles DeGaulle Airport the next morning I felt worse. My gate was L-38, the last gate in concourse L, where I encountered another large artwork, an enormous sleeping cat sculpture, identifying an area of ergonomically shaped sleeping sofas for tired travelers with time between flights. What a nice touch. Unfortunately I had just minutes to board and 23 hours of traveling to do to get back to Cincinnati and my 5 hour layover was in Boston, not Paris. By the time I got home it was near midnight and it was clear I was not alone; Covid-19 had been my travel companion (a second, positive test confirmed it). Five days of Paxlovid and ten days of self-isolation later I can reflect back on this European trip and finish this report.

The trip actually had begun three weeks earlier in Bristol, England, for a conference at the Royal Photographic Society “British Photography Since 1972.” I was particularly interested in the conference topic as I lived and worked in the UK from 1971 through 1982 and had been a contributor to the British photographic scene in those early years. In the ‘80s I directed a photography gallery for the Welsh Arts Council not far from Bristol, in Cardiff. An added bonus, barely 20 feet from the RPS, was Martin Parr’s Foundation.

Parr is the reigning superstar of British photography. I had published his work twice when he was quite young: once in 1975 for a long article (45 pages, 77 photography) on British photography since WWII and then in 1979 in a book surveying the photography collection of the Arts Council of Great Britain (even buying his work so it could appear in the book). Martin arranged to meet me the day before the conference, and it turned out that evening his Foundation was opening an exhibition (naked portraits of people attending the summer Glastonbury Music Festival). It was my first time back in England in decades. My last night I sat reading in the sun on Bristol’s town green, visited the Arnolfini Gallery bookstore, and shared a table with an unknown woman in a Chinese vegetarian restaurant, who then invited me to an opera at Bristol’s Old Vic theatre – a pleasant and perfect denouement. The next day required four trains and a taxi (should have been just three trains but various trains had been cancelled) to get to Gatwick Airport for the (misnamed) EasyJet flight to Marseille, reaching Arles near midnight. Maybe it’s my age but travel seems to be more complicated and less fun than it once was; but I still like the being there part.

Mark Twain, who famously said that when he dies he hopes it will be in Cincinnati (because everything happens there 20 years later), wrote in Innocents Abroad “Travel is fatal to prejudice, bigotry, and narrow-mindedness… “ and recommended it as something sorely needed by most Americans. Someone else (can’t remember who) once wrote that by traveling you actually learn more about where you’ve come from than where you go, an observation complimented by Terry Pratchett in A Hat Full of Sky, writing “Coming back to where you started is not the same as never leaving.” I subscribe to all these sentiments, and especially another by the American photographer Diane Arbus, who wrote “My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been.” It can mean even a street you’ve never been down, or – hopefully – an article you may read in an on-line art publication.

William Messer is a photographer, curator and critic based in Cincinnati, Ohio. He has written for numerous publications in a dozen countries and curated/ organized more than 100 exhibitions presented in nearly 40 countries. For the past 14 years he has curated photography exhibitions at Iris BookCafe and Gallery in Cincinnati. He currently is a Vice-President of l’Association International des Critiques d’Art (AICA) in Paris and founded its Commission on Censorship and Freedom of Expression.

Messer wrote the first American report on what was then the seventh Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie in Arles, France in 1976. In the summer of 2022, after a seven year absence, he returned to Arles to experience his 40th Rencontres de la Photographie and produce this report.

For a short video glimpse of les Rencontres d’Arles 2022: https://player.vimeo.com/video/754914888?h=4636eebeba&autoplay=1&color=e8beff&title=0&byline=0&portrait=0=0&byline=0&portrait=0