TODT’s Hopeful Monster opened at Hudson Jones Gallery at 1110 Alfred St. in Cincinnati’s industrial pocket, Camp Washington, on the 21st of May, beginning what is sure to be an exciting extension of the curatorial oeuvre of gallery director Angela Jones. TODT is an artist collective that originally consisted of four members: Brother, Brother, Sister, and Brother-in- law. They are quite literally related. The collective is presently comprised of just Brother and Sister, the other Brother now dead, and the in- law excommunicated. I spoke with the remaining Brother, whom I’ll not name, at his art bar, The Rake’s End, in Cincinnati’s Brighton neighborhood, on a cool Friday evening. He confirmed that the collective would push forward in creative pursuits until death claims ability. The Rake’s End is full of the collective’s artwork to the same extent that the Gallery is, except that all of the sculptures hang from the high walls. There are amputated mutant mannequins with T.V. protrusions, drawings of fetuses in dark wombs, drawings that resemble agricultural diagrams obscured by basement science, tableaux-esque sculptures that blend photography and light and nightmare, and paintings that echo Francis Bacon and the German ethos of Kiefer. Visit the exhibition and then stop by the bar for a drink, say hi to the owner. He wears glasses, moves quickly and is more or less without hair on his head. The collective is nearly thirty-eight years old now, Hopeful Monster is essentially a retrospective, and the voracious appetite of its wasteland marauder personality would seem as apt as ever, fingers and heart pulsing with creative fervor ready to baptize the bastard infant of industry and man flesh anew with found object and glue.

I approached the bar, where I had been before, and found him sitting on the curb across from the entrance, casually drinking coffee and observing nothing much at all. We talked for two hours, all while the bar was being a bar: bands loading in, sound checks amuck, and patrons being thirsty and thirsty again.

First it is important to understand that the group emerged out of 1980s New York, which simmered in the tension butter of Reaganomics and The Ramones. Judy is a punk and Reagan is bunk. TODT didn’t necessarily identify with punk but definitely had no love for Reagan. TODT was contemporaneous with the likes of Jeff Koons, and being of the 80s and New York has taken cues from the commodity culture defined by Warhol and Pop. The group’s career has spanned temporally and geographically, and their output has sustained its personality despite a waxing and waning institutional reception. They have been loved and vilified. They were part of The Whitney Biennial in 1985 and exhibited at PS1 in 1983. Their accolades are impressive and yet monstrous commercial success has never smiled on TODT. Yet, it seems to matter very little. They are self-taught, self-made, answer to no master, practice a shrewd scavenging, and make everything out of everything.

TODT is tied to the German word tod meaning death, and tot Catalan for everything, and also references the Third Reich via Fritz Todt who was a sort of public works administrator behind “Organization Todt” dedicated to civil and military engineering of the greatest efficiency; very little of the human sacrifice necessitated therein mattering much at all.[1]

When we spoke I was informed that this Fascist association is perhaps the source of TODT’s vilified reputation; however I felt assured that no one in the group is a Fascist and that the association is more a commentary on the state of humanity rather than a political allegiance. The tension between tot and tod is also extremely significant and represents the absolute lack of resolution that suffuses all of the strange permutations of the group’s oeuvre.

There is a complete absence of singularity and resolution surging through the genetic apparatus of aesthetic amalgams that comprises the group’s work, recessive genes rising hopefully to the surface only to be decapitated by the great tension of omnipotent observation that contends for nothing but the undoing of existing. Arguments of philosophy swim in traces of Duchamp to a soundtrack of the clambering ghost hooves of fetal pigs.

steel, wood, leather, mixed plastics

Upon entering the gallery I was confronted by a pair of industrial sculptures, perhaps the most Duchampian of the spread entitled Sentry and Reaper. Both sculptures feature agricultural machines obfuscated and transmogrified with found objects quickly understood as cold instruments of death, poised and at the ready. Reaper perches four scythes atop a reaper, as if ready to cull the metropolis, bodies falling and wilting like stalks of human corn. Sentry is outfitted with a steely crossbow loaded with a chilling quiver of murderous arrows, the bow cocked and ready to explode with sterling flesh- piercing strength. The found objects in both pieces exemplify the appetite with which the group searches for anything that might make formal sense. The forms are paramount to the content; the author here is dead. The associations we as viewers bring to the installation are where the content lies. The combination of agricultural machinery and deadly weapons is the marriage of sensational and banal where a nightmarish tension elucidates discomfort.

mixed media, plastics

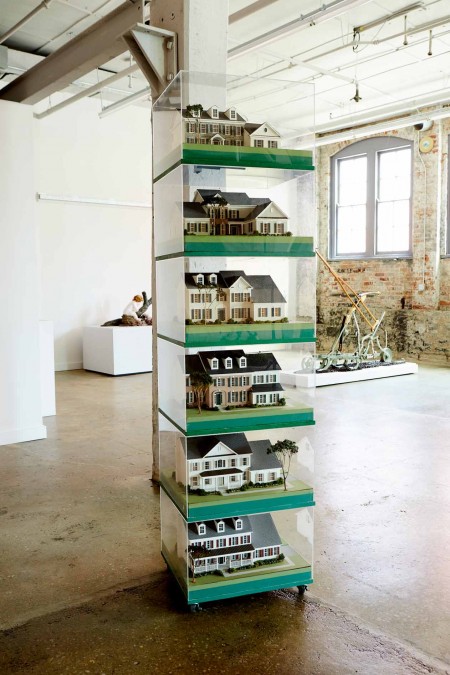

Turning to the right the viewer is met with Cull de Sac. Plastic dioramas featuring idyllic suburban homes are stacked atop one another reaching head height. The models, depicting carbon copy homes with which we are all familiar as Americans, imply an expectation. Whereas almost every other work is completed with an obvious element of horrible violence, nothing lurks in the dark windows of the silent houses. The surprise in Cull de Sac is the lack thereof. The silence is chilling and provides a dynamic aesthetic foil for the rest of the work, where the madness is palpable.

To the right just behind Cull de Sac is a row of forlorn stuffed animals aptly named Unstuffed Animals. Each specimen is a carefully selected animal friend of initially botched design. These stuffed animals beg the question “What schmuck designed these in first place?” and “Who ever would have wanted to cuddle that sad sack?” Each plush corpus is torn open. The stuffing ripped asunder reveals carefully designed plastic innards painted with brightly colored vein systems, puffy musculature, and general suggestions of bloodiness. These sad furry friends still seem very much alive though, as if still being worked on, suspended in the OR, clinging to a life support that’s been long distracted or perhaps laid off, unplugged.

acrylic, pencil, pen on paper

Just above Unstuffed Animals is a series of story bookish drawings entitled TOT Guard 1-8. Each drawing features a small child and each child is variously shackled or bedecked with bondage. Strapped with leather to a high chair, these little babes seem unsurprised by their lack of personal sovereignty or control. Looking at them initially I was slow to notice the shackles and chains snaking around the pudgy bodies of these innocents. Once again a certain nihilistic quality of black humor stabs at our understanding of goodness as this notion is massaged and questioned in arguments from every side.

acrylic, collage on paper, 2013-2016

Proceeding around the gallery to an outcropping of wall that negotiates the gallery’s industrial past effectively is an astounding collection of Thirty—Untitled Paintings on Paper. These are the most recent works from TODT, ranging from 2013-2016; their freshness is maligned by the yellowy varnish that is thickly sweated like human angst across their tumultuous surfaces. The tops of the pages on which they are painted still bare the binding holes, which leave telling traces of how they were ripped from the same pad of paper. These drawings are figurative. The figures matter very little, as they are not to be identified with. They are rendered with a certain degree of incompletion that is almost angry or provoking anger. They are pocked with black vinyl sticker lettering, not the letters so much as the strips that divide the letters, which holds their contours hostage in a manner with which Leonard Baskin would be pleased. Each sheet of paper is the same size, which lends the personality a very intentional series. The formal composition is camped in propaganda and public service posters of the last century and half. Phrases like “Mind the gap!” or “Watch your fingers around the saw blade,” or “Friendly fire is deadly fire,” or “Don’t let electrocution steal your life away,” are all very palpable; the violence of folly is once again thick and languid like an ever-present lurching slug of time, indicating repeated mistakes.

Alongside these drawings, hung on the wall, are a series of found object sculptures that function as sarcastic Duchampian one-liners that belie humanity and our notions of permanence. On the floor below is a red plastic dog with a human arm in its mouth, a tyrannical Fido to ruin your summer pleasure.

These sculptures, staples of ethos in the rambling stereologue of TODT’s collective consciousness, give way to the largest drawing in the exhibition. The drawing is entitled American Buffalo and well represents the Natural History valence of TODT’s aesthetic, again with grim-smiling under-nailings of self inflicted industrial punishment, searching and never finding, and outsider mythos. A family is driving its camper along a road somewhere in Montana, and looks as if it is most definitely going to clip the hooves of a startled Buffalo that has careened into their roadway. The posturing of the vehicle in confrontation with the buffalo implies a stomach churning incision that instills personal fear for your own extremities. The drawing is varnished heavily, and paletted to evoke sun bleaching. It is hung away from the wall just slightly, which only intensifies the suspension of cataclysm.

mixed plastics

A series of sculptural displays that resemble road-side attractions, and rest-stop rattlesnake cages are in the back center arena of the gallery. The three most elevated of the six or seven present, each stand atop its own pedestal and depict cautious children approaching vicious vipers poised in striking. The formal context of museum display coupled with the venomous reality of lethal consequence is discursive and undermines the distillation of natural history museums while also elucidating every parent’s nightmare. The Hummel like figurines appropriated in the sculptures sensationalize and threaten to destroy the banal, pointing a loaded gun at our consumer culture and contribute an endless list of completely useless pursuits and commodities.

It would be very easy for one to wax poetic about the confluence of terror that gurgles like an acid river through TODT’s work in countless stanzas. What I think is most important is to realize the creative behemoth that is TODT. Although it is very easy to pick one thing about their work to focus on, and also to call up associations like Jeff Koons, Paul McCarthy, Marcel Duchamp, Hitler, Nietzsche, Nagarjuna, and so many others, TODT’s work represents none of these and as an artistic entity they may owe precedent but almost never could one call them out for anything resembling allegiance. Instead TODT’s work is camped in the myriad confluence of so many different ideas and the arguments across time that have attempted to negotiate them and argue them toward finality, of which there is none. TODT’s work suspends the human problem without angled critique, slathers it in fake blood, and laughs callously into the void. I highly recommend their work to everyone and suggest you see it for yourself.

–Jack Wood

[1] Nadal-Melsio, Sara. “TODT: Negative Theologies.” University of Pennsylvania, n.d. Web. TODT: As If, Area 919, Philadelphia, Sept. 25-Nov. 8, 2008

Great Show. The 30 paintings on paper where magnificent. Thanks for including how they were made.