“Art is one of the oldest forms of creative expression. . .but often everything is explained in terms of the white male,” Jymi Bolden, black and male and himself an artist, told me when we met to talk about black artists today and their inclusion/exclusion in the visual arts world. The conversation naturally moved to include Art Beyond Boundaries gallery, established by Bolden in February 2007 to feature artists with disabilities. His own art is with a camera.

Besides heading Art Beyond Boundaries (1410 Main Street in Over-the-Rhine) Bolden continues his own art-making career in photography. Right now “Uprising,” an outdoor exhibition of printed works “by Black artists calling for justice” is on view outside the Kennedy Heights Arts Center; it was curated by Bolden and can be seen through November 28th.

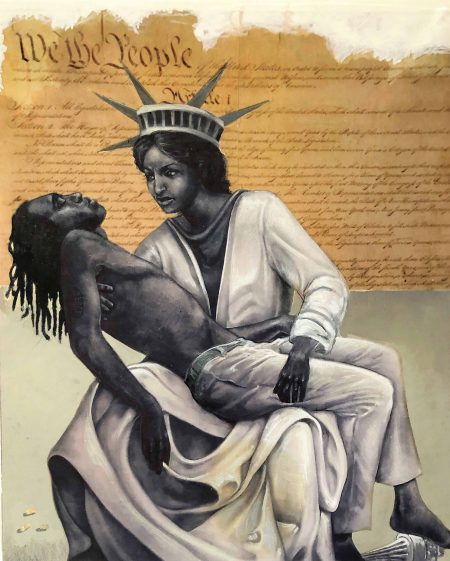

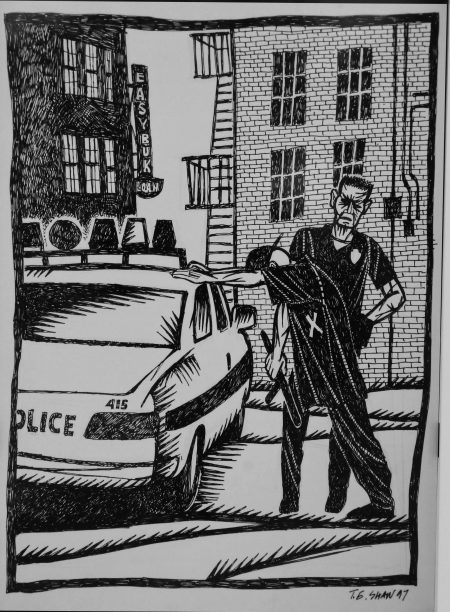

“Uprising” is an exhibition unique in my experience. It’s outdoors, which is rare for art exhibitions except for sculpture, and its visitors are usually in automobiles moving slowly through on a driveway looping past the Arts Center at 6546 Montgomery Road and accessible for entrance and exit on Montgomery Road. Or, a visitor can simply walk through on foot. The show may be seen any time during daylight hours. The ten artists included in the exhibition are Melvin Grier, Jimi Jones, Cynthia Lockhart, Cherie Garces, Terence Hammonds, Gee Horton, Hannah “Jonesy” Jones, Ricci Michaels, Gilbert Young and Thom Shaw. The original works were photographed in high-resolution and printed large-scale (four feet by six feet) using weather resistant materials for this outside installation. If seeing pictures in a gallery has become old hat to you, give “Uprising” a try. It’s a lively show. Post card size reproductions and also 20 inch by 30 inch prints of the works on view can be purchased through the Arts Center.

Bolden and I talked about the expansion of the art market place in recent years. New people have been exposed to the concept of art and the once highly specialized market has grown. “Art is one of the oldest forms of creative expression,” he said, “but often everything is explained in terms of the white male. This is a particular challenge for black artists although it doesn’t get spoken about much – intimidated by political correctness?” But his own experience includes expansion and growth, a new awareness of a greater audience. “There’s more opportunity now, the quality of exposure has increased,” he said. “There’s been a rethinking of museum gallery structure, and development of technology to enable that. Also – the speed in which information is passed now impacts the perception and perspective of expression. There are movements in progress that are still too new to know if they are lasting. In the end, time and history will tell us what’s good and what’s bad. . . but the greater exposure now available for the arts is good, certainly, and particularly for artists of color.”

We talked about his early recognition that he saw things a little differently than his fellows. He could draw, he went to classes at the Art Museum as a kid . “You have remote role models,” he told me. In the early 1960’s he entered art contests sponsored by Shillito’s department store and other similar ventures, placing first in one when he was a sophomore in high school. This and other successes gave him confidence and the recognition that “This is what I want to do.” He left school and looked for a job.

“I went out with a rag tag portfolio of drawings, looking for work. ‘Do you want an artist?’ I said.” Doors closed on the black kid. There was occasional encouragement but not enough and Jymi gave up art for fifteen years. Then someone gave him a camera and before long he knew what he wanted to do from then on. “The camera has taken me all over the world,” he said, in appreciation of the widening of his experience and increased understanding of what goes on in venues not necessarily his own. Ten years as photography editor at City Beat contributed immensely to both those goals.

The melding of views (scholastic/journalistic) is not the easiest accomplishment going, but Bolden has it well in hand. I asked if he could tell me how he managed that, and got an interesting answer back: “Sure, I’d be happy to! I was able to seamlessly translate my fine art documentary photography conceptual approach to the fact oriented journalistic traditions. I have my friend and journalism mentor, Melvin Grier to thank for the ease in my photographic transformation. I interned with Melvin while attending the Art Academy of Cincinnati in the 80’s.” The art world is pleasantly lightened by this kind of story, which is not too unusual and always good to hear.

We talked about the particular aspects of photography as an art. “Historically, photography has been a stepchild in art-making and art appreciation, but the pendulum swings back and forth,” Bolden said. “Originally, crucial decisions were made in the dark room but technology has killed much of this. However, because of new and different technical apparatus photography continues to be an expression of fine art.”

Because his own career has combined making art and establishing a gallery showing art I asked how he balances these two objectives. “The energy now expended on the gallery for some fourteen or fifteen years once was only on my work, but it produces another sort of gratification. I don’t truly regret it – it’s added another dimension to my life,” he said. “It’s gone from an idea for a one night stand to becoming a viable exhibition venue in the greater Cincinnati arts world. It’s encouraging to me that so many younger creative people are discovering the value of artistic expressions.”

The artists in all fields are, in fact, the people who tell us what’s really going on, although we may not understand them immediately. Bolden is among those who shape our thinking, whether we know it or not.

–Jane Durrell