“A Sense of Home: New Quilts by Heather Jones” complements the Taft Museum of Art’s “Elegant Geometry: British and American Mosaic Patchwork Quilts” exhibition. (See aeqai.com, November 2017.)

Jones sees modern quilting as “look(ing) at traditional quilting and then do(ing) its own thing.” 1 For this quilt maker, “its own thing” marries tradition and contemporary abstract art in quilts that are meant to be used and “paintings”—smaller pieced works stretched over wood supports.

Tamara Muente, the associate curator of the Taft, invited Jones to exhibit in the Sinton Gallery, which showcases local artists. Its purpose is to continue Anna and Charles Taft’s desire to educate and inspire the people of Cincinnati. Artists chosen are tasked with creating new works in response to the collection, the house or its history, and the people who lived there. Jones chose a diverse and eclectic mix including paintings, decorative arts, and architectural elements for her eight pieces.

Born in 1976 in Dayton, Jones, who currently lives in Springboro with her husband and two children, studied art history at the University of Cincinnati. She was also painting representational work, mostly landscapes and still lifes. She was drawn to quilting because her septuagenarian great-great Aunt Ollie had made a baby quilt for her. As a teenager, Jones collected vintage quilts, but didn’t begin quilting herself until 2010 because she found the process intimidating.

Jones’ aesthetic is an amalgam of traditional quilt patterns, new designs inspired by her environment, and contemporary abstract painting. Her husband, Jeffrey Cortland Jones, who is a minimalist abstract painter and professor at the University of Dayton, introduced her to the work of Josef Albers, Mark Rothko, and Robert Ryman. Jones added Ellsworth Kelly and Sean Scully to the list. All of those painters influenced her desire “to pare things down to their most essential elements.” 2 The bold abstract designs of quilter Denyse Schmidt and the improvisational approach to composition of the quilters of Gee’s Bend also migrated into Jones’s style. 3

Like traditional quilters who took what they saw around them to devise patterns such as flying geese, rail fence, churn dash, and log cabin, 4 Jones uses her surroundings to spark her creativity. She gravitates to mundane things such as grain silos, painted parking lot grids, industrial machine components, agricultural buildings, etc. 5

For this exhibition, the artist selected works that she was visually drawn to and, as I mentioned, it was a diverse and eclectic lot. It included the siding of the original house in What You Can’t See (Sometimes Jones’s titles “are lyrics to songs or lines of poetry; other times they are words that I like the sound of when they are strung together” 6 ), an 18th-century Chinese vase for From the Darkness, and John Singer Sargent’s 1887 portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson for Don’t Look Back.

In From the Darkness, the artist keyed off the shutters in one of the detailed vignettes on the 18th-century Chinese Rouleau Vase with Scenes of Silk Culture and Rice Planting. Jones reversed the colors and increased the scale to stress its essential graphic qualities. 7

Jones took the thick, spontaneous brushwork of the shaggy carpet in Sargent’s 1887 portrait of Robert Louis Stevenson as a cue to improvise the composition of Don’t Look Back. The pieced work is stretched over a wood support, and Jones considers these pieces paintings (her husband encouraged her to use fabric as paint 8). She likes the way these stretched pieces “straddle the line between art and craft, and add to that dialogue as well. I do refer to them as paintings, as that is what they are meant to be in my eyes.” 9 But she does intend her quilts to be used. She likes to make things with a strong design quality, but it’s “all the better” if it’s functional. 10

One example where Jones turned tradition on its head—or at least tilted it—is There’ll Be One More. She’s rotated a traditional log cabin quilt block to imitate the chevrons of Federal-style wood mantle in the Barbizon Gallery, but turn Jones’s diamonds back 90 degrees, and it’s pure Frank Stella.

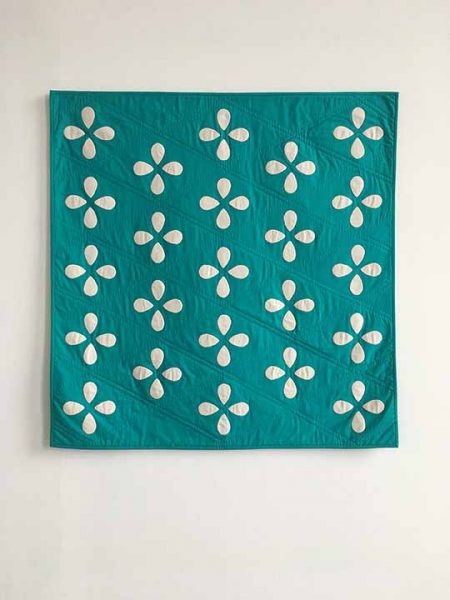

The relationship with the collection is unmistakable in Finds the Grace; the late 18th-century Bowl with Rice-Grain Motif that inspired it sits next to Jones’s quilt. The artist has replicated the surface design, but quilt and bowl share something else that may be less obvious: both Jones and the ceramist(s) used extremely labor-intensive and exacting processes to create their works. Jones traced the outline of 92 petal-like shapes on a double layer of white cloth, stitched along the outline, and cut out each one. She then slit one of the layers and turned each piece inside out to hide the seam and to give them a dimensional quality. Each was then appliquéd by hand on the turquoise fabric. I won’t even attempt to explain the techniques used to make the stunning bowl.

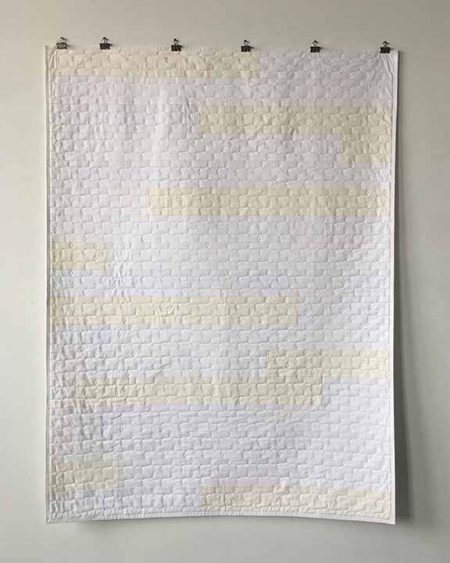

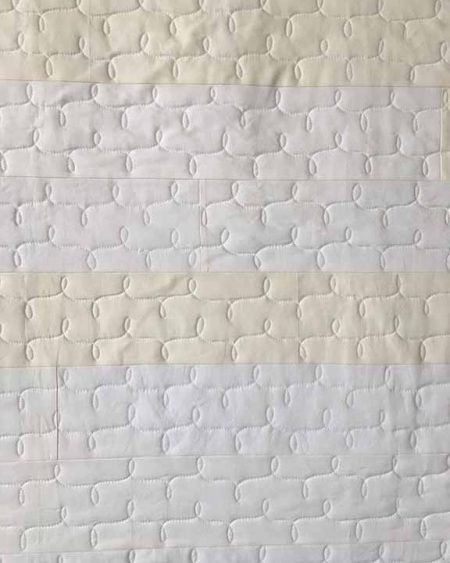

The connection between Jones’s The Wind Calls and Joseph Mallard William Turner’s c. 1845 Europa and the Bull is more tenuous; the regimented rectangles of Jones’ quilt hardly represent the atmospherics of the painting. The wall label for the quilt argues that the horizontal format and palette reference the Turner, and but that’s it and not quite enough for me to tie them together.

Although Jones cites the house’s original 1820s wood siding in What You Can’t See as her reference, the quilt immediately reminded me of Ryman’s white paintings. She used four white fabrics that are so close in tone that they read as a single hue. (The differences are more apparent in the photograph than in the gallery.)

The artist has overstitched the strips, which are the width of a piece of the siding, with a running pattern that looks like parentheses with a teardrop at the point where the two curving lines converge. Here the machine stitching might simulate the textures of Ryman’s sometimes visible brushstrokes, but this pattern also appears in other quilts, including There’ll Be One More and From the Darkness.

Whether the linkage between Jones’s quilts and the treasures of the Taft is close or a bit of a stretch, spending some time bouncing between them makes for a pleasant and thought-provoking visit.

–Karen S. Chambers

“A Sense of Home: New Quilts by Heather Jones,” Taft Museum of Art, 316 Pike St., Cincinnati, OH 45202. 513-241-0343. www.taftmuseum.org. Through February 18, 2018.

END NOTES

1 Meet Heather Jones: Modern Quilter and Designer, Creativebug Studios, c. 2012, video.

2 Ibid.

3 “A Sense of Home: New Quilts by Heather Jones,” interview, Portico, November 2017.

4 “A Sense of Home: New Quilts by Heather Jones,” Taft Museum of Art, brochure.

5 Portico, op.cit.

6 Email to author, December 16, 2017.

7 “A Sense of Home: New Quilts by Heather Jones,” Taft Museum of Art, exhibition label.

8 Email to author, December 15, 2017.

9 Ibid.

10 Meet Heather Jones: Modern Quilter and Designer, op. cit.