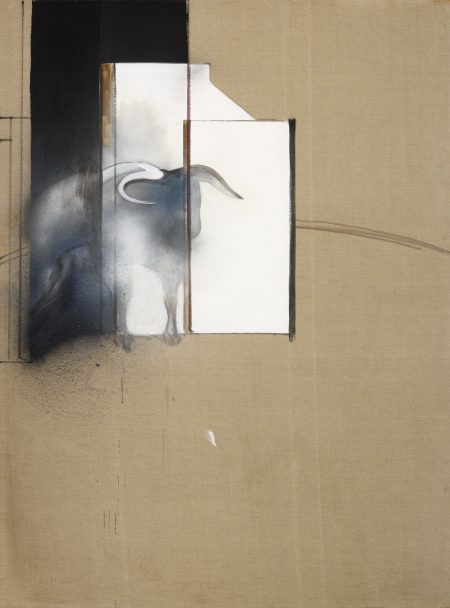

Francis Bacon’s last painting is mostly raw canvas. It depicts a single form: a ghostly bull bridging the blackness of an open doorway. A bit like one of those optical illusions where a shape simultaneously pushes forward and recedes, the bull alternates between presence and absence; charge and rest. Study for a Bull (1991) derives its power from that ambiguity. The eye darts back and forth between the light and dark portions of the bull’s body, resting on the deadly curve of its horns before falling back to the wispy angle of its haunches and out again to the dissolving ring of the arena, which opens up to the edge of the canvas and encompasses the world outside.

Study for a Bull is a far cry from the Irish-born English painter’s screaming popes and smeary carcasses, but it is no less electrifying. It left me stunned when I saw it at the Museum of Fine Arts Houston, in the exhibition Francis Bacon: Late Paintings (which closed on August 16th). Consisting of 40 works, mostly from the 1970s and 80s, this was the first museum survey of Bacon’s work in the United States since the retrospective at the Met more than ten years ago. Late Paintings was organized by the Centre Pompidou in Paris where it was first shown with the title Bacon: En toutes Lettres. There, curator Didier Ottinger refracted Bacon’s late period through the lens of the artist’s many literary influences. In the MFAH iteration, which included 40 of the 60 works that Ottinger originally selected, the literary refraction took a backseat to an emphasis on the tragedy that unfolded for Bacon when his partner, George Dyer, took his own life two days before the opening of Bacon’s retrospective in 1971. Thankfully, Ottinger’s superb catalog Francis Bacon: Books and Paintings also accompanies this exhibition, and it includes Ottinger’s own essay “Bacon Spelled Out” and some outstanding essays on the artist’s relationship to literature, with discussions of Aeschylus, Gilles Deleuze, Georges Bataille, T.S. Eliot, and others.

As one would expect from a Francis Bacon show, there was no shortage of the macabre. We are treated to visions of meat, copulation, and death, but also a jouissance, a tenderness hidden within the sadism that renders the spiritual horror more complex. Before seeing these later paintings in person, I hadn’t thought of Bacon as much of a colorist. Many of his earlier works borrow limited palettes of Velazquez and El Greco’s religious paintings, getting mileage more from chiaroscuro than chromatism. But here, the colors seem to vibrate off the walls: buttery violets, vivid ultramarines, meaty crimsons, and even fields of pure cadmium reds and yellows. Looking at Triptych (1967) the thought crossed my mind that this could be a sinister, alternate-universe doppelganger David Hockney.

“I wanted to paint the scream more than the horror,” Bacon told art critic David Sylvester.[1] For Bacon, the body is less interesting than the forces that move through it. “The violence of a hiccup, of a need to vomit, but also an involuntary smile.”[2] The figure is a means to that end. Just as the Impressionists dismantled vision, Bacon dismantles the psyche. Particularly in the case of his portraits, with their fractal-butcher faces, the paintings reach into the skull and reroute the wires, scrambling the face-perception code. It’s only through this rewiring that we are permitted to see the underlying forces. Bacon’s paintings are like the atom smashing machines that allow us to peer into the subatomic structure of reality, the elemental particles that generate mass. Moving among them, I felt as if I were traversing powerful gravitational fields emanating from between the thin layers of paint.

Every work here is framed and behind glass, which was Bacon’s preference. In another interview he told David Sylvester that the glass places a distance between the onlooker and the painting. “I like, as it were, the removal of the object as far as possible.”[3] Looking at these paintings through glass, while wearing my facemask (and occasionally stopping to wipe condensation from my glasses), I felt an absurd identification with that removal. Like the mask, the glass offers safety that extends both directions: Without it, these paintings would suck the air out of the room; they would implode by their own force of gravity.

One of the heaviest paintings here is placed at the beginning. In Self-Portrait (1971) we see the likeness of the painter emerging from shadow. His face appears twisted, bruised, and out of joint. The small painting exerts a dark power, as if the skin of oil paint conceals a gravitational singularity. The glass captures the painting in a kind of airless vacuum, arresting the face at the moment of its implosion. Through the glass, we are permitted a glimpse into a soul’s dark event horizon. In Triptych (1970), two men seated on aerial trapeze contraptions form an anti-gravity machine that renders weightless two figures wrestling in a blue ring.

The exhibition’s center of gravity comes in the second gallery, which is dominated by two large triptychs. In Memory of George Dyer (1971) encircles the artist’s partner’s final moments, refracted through a central panel that turns on imagery from T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land”. It hangs across from the more metaphysical Triptych August 1972, in which three portraits of Dyer, body drifting out of shape, are framed by a darkened doorway that seems to reach out and envelope his disintegrating form. The space between these triptychs might be encapsulated in a quote from George Bataille appearing in the exhibition catalog:

“In the violence of the overcoming, in the disorder of my laughter and my sobbing, in the excess of raptures that shatter me, I seize on the similarity between a horror and a voluptuousness that goes beyond me, between an ultimate pain and an unbearable joy!”[4]

The third gallery held, for me, the most surprises. I simply loved two Sand Dune paintings (1981 and 1983), which show clouds of biomorphic sand moving through a turnstile or escaping a box. Even by Francis Bacon standards, they’re bizarre. Bacon didn’t paint many landscapes during his career, and when he did, he couldn’t seem to resist the urge to turn the landscape into a body. As with the body, his interest is in showing forces rather than depicting a likeness. In clouds of sand or running water splashing into a sink (1982’s Water from a Running Tap, once again conjuring visions of a nefarious David Hockney doppelganger), human forces erupt through and threaten to obliterate the form. It’s here, in his non-figurative works that we see for the first time large swaths of exposed canvas and aerosol paints.

“At the end of the day, it’s all we want. Voluptuousness,” Francis Bacon told BBC host Melvyn Bragg in a 1985 documentary that screens on loop at the end of the exhibition. Sitting in a London cafe, Bragg responds: “I actually think you want to live in a state of voluptuousness.” The camera pans out as Bacon’s face lights up. “Yes, a state of voluptuousness. Whatever it is. Everything else is a falling away.” In the final rooms, things indeed fall away. The paint of the bodies are more thinly applied, even graphic, and they float in fields of pure color or exposed canvas. By the time we reach Study for a Bull, in which nearly everything has fallen away, all that is left is pure voluptuousness; an “ultimate pain and an unbearable joy.”

–Steve Kemple

[1] David Sylvester. The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon, London: Thames & Hudson, 1987. pg 43.

[2] Gilles Deleuze, trans. Daniel W. Smith. The Logic of Sensation. Minneapolis: University of Minnestoa Press. pg. xxix

[3] “Because I use no varnishes or anything of that kind, and because of the very flat way I paint, the glass helps to unify the picture. I also like the distance between what has been done and the onlooker that the glass creates; I like, as it were, the removal of the object as far as possible.” (David Sylvester. The Brutality of Fact: Interviews with Francis Bacon. pg. 86)

[4] Georges Bataille. The Tears of Eros (1961) quoted by Bernard Blistène in the Preface to Francis Bacon: Books and Painting. London: Thames & Hudson, 2019. p13.