“In the middle of the night, peering intensely at some small thing, I do become lost, consumed by the intensity of this condensed universe” – Christian Schmit (from Artist Statement for Lost in the Making)

There is something foreboding about diving solo into a nocturnal inner world, especially of the diminutive sort. From The Adventures of Alice Through the Looking Glass and Gulliver’s Travels, we know that rules can change in the realm of the small. Standard logic may not follow, the terrain is not necessarily benign, and the road out is not assured. It is this world that Christian Schmit invites us to explore in “Lost In The Making”.

At first glance, the sculptures in ”Lost In The Making”, emanate the toy-like charm and delight of the miniature. The wonder of things small can be as powerful as the wonder of the gigantic. It conjures the question, “how on Earth is that done?” and draws one in close in order to examine. Schmit is armed with a jeweler’s eye for detail, and his craft, some “serious labor”, as I overheard one viewer express, is impeccable, in a jaw-dropping kind of way. Because Schmit’s materials are simple and mostly monochrome – unpainted brown paper and cardboard – his elegant, highly observant constructions are met with very few chromatic distractions, saved for a rare moment of emphasis.

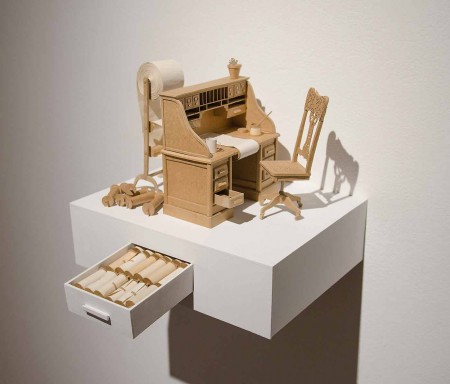

Schmit’s sculpture opens one’s imagination to the tactile as well as the microcosmic, for we touch paper every day. In a world where so little is done by hand anymore, the visceral awareness of the capacity of a human hand here is acute. I took a long time to make it past the very first work in the show, Scroll Desk, due to marveling at the “routed” face panel of a drawer in the desk. In that open drawer was a miniscule open “matchbox”, and in that matchbox, the tiniest white shell I have ever seen.

The exhibition consists of nineteen wall-mounted plinths that appear as stages for the scenes of a drama. As one steps from plinth to plinth, the initial playfulness moves into darker territory of the creative realm: delusion, isolation, and self-doubt. Viewer becomes voyeur, witness to and investigator of the circumstances of an artist’s private, solitary cosmos. In the scale of this world, ordinary objects take on great gravity. Chairs, from the easy to the ornate carved desk variety, to stools and folding metal, recur in many of the works, and seem to be stand-ins for the protagonist of this drama. Drawers containing “facts”, explanations, and prototypes protrude from plant pots and furniture, and are also inset, some open, some closed, like secrets, in many of the plinths. In Confabulation, a library filled with books, a phonograph, a floor lamp, and a film projector contains an easy chair occupied by the breastplate from a suit of armor. The term “confabulation” refers to the distortion or fabrication of memories about oneself or the world; connected to the breastplate it points us in the direction of Don Quixote. This reference lends our protagonist the character of a kindly and earnest but delusional dreamer. A drawer below, emerging from the plinth, offers a “Book of Facts” as counterpoint to the fictions inherent in the music, stories, and films.

Coffee cups, ladders, books, paper stacks and scrolls, little spheres of shredded paper, lamps, and projectors are repeated throughout the sculptural vignettes. In The Four Necessities, a display of significant objects give further insight into the story: a film projector and screen, a flatfile filled with pink erasers, a coffee-making contraption, and an open suitcase with escape ladder descending into the void. In the plinth, an open drawer with diagrams and writing explaining the purpose of different projection lenses provides a glimpse of sentiment: ”Lens Key: Their meanings, for what it’s worth: A. For compounding problems. B. For forgetting painful things. C. For merely tolerating you.”

If creature comforts and mundane objects of home populate Schmit’s constructed world, so too do the struggles, self-doubts, disappointments and fragile hopes that inhabit conventional reality. In Perception Complex, an imposing chair and podium tower over a low chair and desk. In the chasm between, hanging knives threaten to impale papers produced at the bottom station. In this case, Schmit’s protagonist appears to be both judge and judged, exchanging places by using trap doors and ladders. In Total Perspective Vortex, the contrast between a large, powerful telescope and its object of focus, a small picture of the universe, and a deep stack of the same image ready to be similarly examined, suggests an inescapable feedback loop. Climbing and descending ladders serve as an important possibility for action in several pieces. The ladders provide a means of withdrawal, escape, or return, as in the aforementioned Necessities and Perception pieces. In A Is For Adjunct, they futilely reach toward the external world. With its ladders leading nowhere, here Schmit renders a chronic hurdle for those seeking full-time employment in academia.

The Paper Mountain depicts a dream of escape that offers solitude with a vast, open perspective. In his tiny world, the protagonist has built a tiny house on high scaffolding, perched on yet another scaffold. It is not so far from where the story begins, inside a shell inside a box inside a desk. In The Poetics of Space, poet and philosopher Gaston Bachelard reminds us of the significance of the shell, which he also considers a home. He says, “The creature that hides and withdraws into its shell is preparing a way out. This is true of the entire scale of metaphors, from the resurrection of a man in his grave, to the sudden outburst of one who has been long silent. If we remain at the heart of the image under consideration, we have the impression that, by staying in the motionlessness of its shell, the creature is preparing temporal explosions, not to say whirlwinds, of being.”

Christian Schmit has brought us a skillfully crafted explosion, blasting open his condensed universe to reveal the curious, anxious, mundane, deluded, caffeine-filled truth of his poetry. No doubt he is busy now, working late into the night, preparing for the next. Perhaps not bigger, but greater.

Susan Byrnes is a Cincinnati-based visual artist whose work encompasses traditional and contemporary forms and practices, including sculpture, multimedia installation, radio broadcasts, writing, and curatorial projects.