“Whenever you are doing a painting or a series, you have to leave something electric in the picture, something horrifying on a personal level.” casual quote by Rand from the Journal of Delacroix

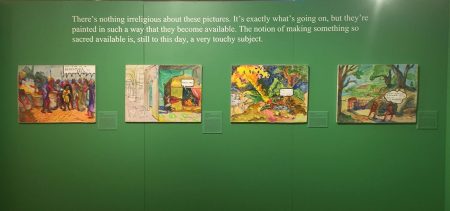

A must-see exhibition held over at the Skirball Museum is Archie Rand’s: “60 Paintings from the Bible”.

Rand, currently a professor at Brooklyn College and a Gugenheim fellow, is known for his signature comic book style and this series is the earliest and largest in his oeuvre.

The paintings are uniformly sized, unframed 16″x20″ acrylics executed in bright, harlequin colors that flow through the gallery like a colorful mural. The exhibition is presented in the order in which the stories appear in the Bible beginning with the expulsion of Adam and Eve to the feats of Samson and episodes of King David and Solomon.

While 20th century Jewish artists (Jack Levine, Raphael and Moses Soyer among others) were breaking through as contemporary American painters with their own trajectory as social realists, other Jewish artists engaged in the trend of hand drawn story-telling. The comic books and pulp fiction publications that came out of this era of graphic novellas appealed to an echelon of readership that relished raw, thrilling drama and violent imagery. Rand cites several Jewish American giants whose contributions galvanized this readership: Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, two Jews from Cleveland, Ohio who created the character of Superman and notables Art Spiegelman and Will Eisner (“Contract with God” 1978). Rand posits that Eisner developed a way of drawing that took advantage of decades earlier film noir visuals, with emotional faces, violent story lines and extreme action shots. “He was a ferocious enemy of anti-semitism whose love and identification of Jewishness carried weight in the imagery and his story line.”

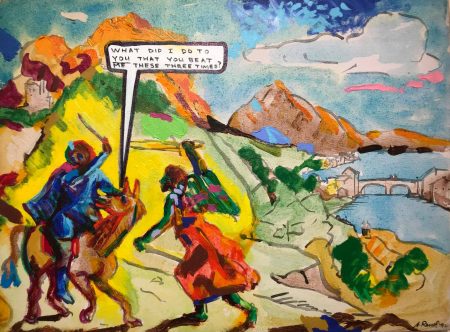

The key alignments of Rand’s work with this brief description of the graphic novel are ‘lifelike pictorials’ that evoke’ vivid imagery’ in the imagination and common vulgarity of language.

A significant component is the nature and use of language in Rand’s paintings.

Like the graphic novellas, Rand’s characters, both human and the deity, speak in floating rectangular speech bubbles. No “thee’s and thou’s” here as Rand uses an unsanitized Hebrew translation, such as would be exclaimed in exasperation on a corner in Brooklyn, that is much more abrupt and direct than the English translations. For example: In one painting, a mission-shy Jeremiah, having been told by the Almighty that he is to go forth with an unwelcome message as God’s servant, weakly questions God’s anointment to be carried out in a hostile foreign terrain. The blast of God’s speech bubble comes out of the sun: “Don’t tell me you are a child. You are going to go where I tell you and do whatever I say!”.

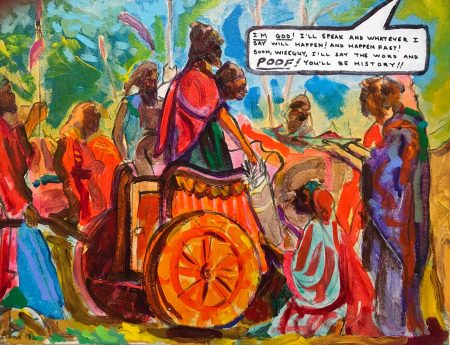

Another example is the rebuke of Ezekiel before the erring prince. God’s thunderous instructions are blasted from the heavens as if He were head of the Mafia:

“I’m God and whatever I speak will happen and happen fast!!”

The Almighty’s patience is worn thin and vexed by his faithless and spineless creatures. In several instances, the copy is lettered for emphasis with headline caps, punctuated with multiple exclamation points and phrasing serially underlined for emphasis in the common black marker.

Rand’s work also speaks to the pathos and humanity as Rand experienced in the Biblical depictions of Rembrandt. In the painting of Abraham preparing to sacrifice his only son Isaac, Abraham determines not to shrink from God’s command despite his paternal love for the boy. Abraham’s expression is extremely stressful, his eyebrows are high upon his forehead as he considers what he is about to do. Upon hearing God’s welcome reprieve, Abraham’s speech bubble is lettered and punctuated in all caps: “I’M HERE!!” as in “FIND ME BEFORE I DO THIS THING!!”, not as the mild English translation implies: “I am here, you have found your humble servant.”

Color is another tool Rand ruthlessly employs like a stun gun, jolting his viewers’ sensitivities. Rand superimposes a contemporary color theory upon classically influenced images. Rand appropriates many of the Biblical etchings of Matthaus Merian, a seventeenth century Swiss-born engraver as prototypes for his compositions.

Several of the paintings portray two segments of the same story in one image, employing bold vibrant strokes in the foreground episode and cooler pastel tones in the spatial recesses of the second episode.

Rand’s rancorous color palette and stylistically brisk brushwork endorse the Jewish traits of ‘garishness’ and ‘vulgarity’ throughout the series. Rand does not shy away from stereotypes and detractors of Jewishness when he directly addresses traits like “vulgarity”, “garishness” in his discussions. His unfiltered, unmodeled colors reflect the sometime vulgarity of authentic Jewishness, a figurative artistic Jewish slap in the face. Rand cites his influences on the vibrant use of color and unadulterated brush strokes as derived from German expressionists Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and August Macke, a leading member of the German Expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter.

“Passover” is lifted entirely from a Merian composition. The Jewish communal roundtable is set before a single window in a jarring red and magenta room. The omission of the left sidewall relieves the composition with an opening onto the cool blue distance on the left side. Rand delineates the entire specifications of the Passover feast with a thin sharpie in the floating rectangular speech bubble.

Archie Rand’s comic book paintings serve up Biblical stories adding fresh perspectives to narratives that have shaped Western Civilization. Tales of morality and humanity unfold as the characters are confronted by the imperatives of God Himself or left to deal with their moral quandaries on their own. Rand makes these classics available by removing aesthetic concerns and addressing language on the level of the common man’s shocking and profane vernacular. Rand’s reformatting of the imagery in colorful comic book visuals, replete with speech bubbles and direct dialogs, makes the humanized experiences more available without being castigated with Jewish censorship.

Rand presents his work proudly as a contribution to the inventive culture of the Diaspora.

The Skirball Museum is open with reservations Tuesdays and Thursdays 11-4pm

Exhibition extended to the end of January 2021

–Marlene Steele