Over-the-Rhine has been home to Art Beyond Boundaries gallery for a decade. Curator Jymi Bolden hosts up to seven shows a year, and proudly claims the 2016 “Photospeak” as his sixtieth exhibit. The gallery features the work of artists with disabilities who live in and around Cincinnati, some of whom are long-time professionals and others promising newcomers. Their entries in the latest show address relationships between vision and language, exploring how documentary, narrative, and experimental genres serve as invitations to dialogue. The results are lyrical and vibrant, moody and sometimes devastating.

The show’s fifty or so pictures create a rhythm that reveals itself gradually, as does the logic of each photograph. Contributors include such accomplished Cincinnati artists as Melvin Grier, Mike Isaacs, Michael Mitchell, Ann Segal, Brad Smith, Bryn Weller, J. Miles Wolf, and Bolden himself. They also include participants from the Osher Lifelong Learning Institution (OLLI), Youth Overcoming Life’s Obstacles (YOLO), and the Center for Independent Living Options summer camp program, as well as interns at Art Beyond Boundaries. The exhibit ranges widely in topic and aesthetic, and as Bolden indicates, every slice deserves consideration. The aim here, however, is to specify a few of the themes and variations that distinguish the exhibition. As the photographs engage their Cincinnati context, they depict bodies in motion and bodies as composing spaces—bodies emerging from an array of textures and shadows while startling contrasts play out between monochrome and color, both across images and within single photos. Whether invoking motion or high-definition tableaux, they revel in ambiguity, yet that fluctuation generates moments of lucid political consciousness.

As “Photospeak” focuses on the process of articulation more than the already said, political and formal claims surge and morph rather than staying still. The photos of J. Miles Wolf, for example, are all motion and energy, as mass transit and flowing crowds give way to blasts of clear-cut neon. In “The Race,” marathon runners mostly blend with the blurred background, though a few bodies spill forward from the picture plane, attaining hyperreal exactness. On the gallery’s opposite wall hangs Ainsley Kellar’s “I Barely Knew Her…But I Miss Her,” its focal character escaping down a half-lit alleyway, fixing our attention while fleeing our gaze. Just as her momentum reverses that of “The Race,” the photo contrasts the color of Wolf’s pieces with a black-and-white palette that accentuates, or perhaps even creates, the alley’s damp shimmer.

Like many of the show’s offerings, Kellar’s pictures examine relations between people and their environments. “Man and Metal Moving through an Existential Life” depicts a traveler negotiating a latticework of steel and glass, an airport-like interior that insinuates his insignificance. Complementing the techno-sublime, an accompanying photo spotlights a lone figure in a cocktail dress, waiting on the dock of a bay as thunderheads approach. Larry Pytlinski of OLLI shows similar concern with the poetics of space, whether photographing a Cuban officer dancing down a dusty street, or a cigar-smoking woman wearing flowers that blend with her red stucco backdrop. Varying the motif, Melissa Hunter accentuates reflective surfaces, studying how storefront glass mirrors people’s inhabitance of the city. While many of the images suggest harmony between embodiment and the built world, Diamond Johnson emphasizes dissonance as her subject (the already mentioned Melissa Hunter) strikes a stylish pose against security bars and grating. The material context shapes our perception of the photos’ characters just as those characters influence our responses to setting. The results are rarely stable or predictable.

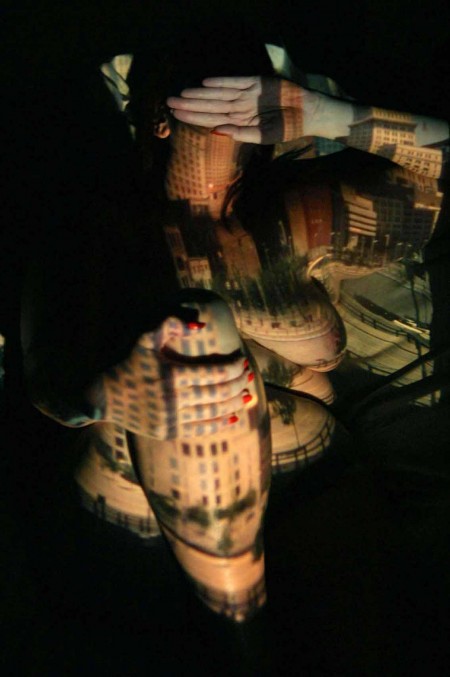

The more nuanced statements of embodied place come from Bolden, whose subjects do not merely interact with their surroundings, but rather find those surroundings projected onto their flesh. In “Anamorphosis #500,” a nude figure attempts to cover herself yet remains partially exposed as images of the city ripple across her shin, neck, forearm, and the hand that shields her face. Limbs protrude from darkness while other parts withdraw; the urban ecology discloses itself in bleary fragments. Other Bolden photographs include bodies that are impossibly elongated, splashed with the patterns of their environment, signaling not reserve but sensual abandon. In a show that asks how photos speak, his images express themselves by degrees, inviting the viewer-listener to invent as much as receive. The dialogic character of “Anamorphosis #500” resonates throughout the exhibit, but finds its closest corollary in Brynn Weller’s “Cinque Terre Graffiti.” At the core of the image exists a figure spray-painted on a wall in Italy, partly hiding her face from onlookers. Names, dates, and declarations of love adorn her body like a veil. Whether she wears the textual overlay comfortably or shrinks from its imposition remains unknown.

Such moments of uncertainty fill the gallery. In the work of Michael Mitchell, a Union soldier holds a flaming US flag while others stand in solemn ceremony. We cannot know whether he is pulling the flag from the pyre or burning it. The fiery object gives the scene its only color; the rest recedes in shades of black and silver. In Thomas Condo’s Rome trilogy, a homeless person stands out against a dark background, her head fully wrapped against the sun. Yet the facelessness also evokes a certain mystery and even hints at pain. Suzanne Fleming-Smith catches heavy clouds reflected in a lily pond just as light breaks through; or look again, and the sky closes off the last rays. A few feet away, another photo features a man bending forward, placing his head against the curve of a cane. As Melvin Grier’s title denotes, here we encounter a “Man Praying.” It cannot be said whether the act indicates devotion, contrition, desperation, or something else altogether. The photos do not speak discourses of resolution but of inquiry.

But however wide-ranging the exhibit’s questions, they often return to the idea of endurance. The stamina of the marathon runner, the graceful aging of Cuban citizens along with their environs, the memory of departure, the solace of spirituality—all these things connote staying power. Fleming-Smith’s “Still Standing” synthesizes the concerns of many pieces with a scene where the poignant and the comic intermingle. It centers on a vast interior, like the wing of an exposition center, empty of people but filled with refuse and signs of decay. In the foreground, a chair perches on legs that look ready to collapse. Bright piles of debris stretch rearward from the object, at once contrasting its tenacity and signaling the inevitability of decline. The chair embodies what Jane Bennett calls “vibrant materiality,” an agency that intersects with that of persons but cannot be equated with it.[1] Such vibrancy inheres in the transitional character of objects, their distinctive processes of becoming and transformation. In that light, the chair is only the most prominent instance of a condition that extends throughout the pictured space, subsumes the photograph itself, and transgresses the frame.

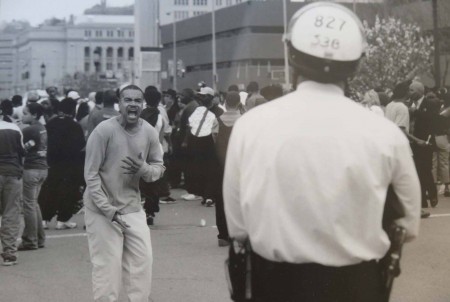

As the object radiates persistence, it draws out political threads that run through the exhibit. Whether in Pytlinski’s and Jane Hopson’s depictions of Cuban nationalism, or Mitchell’s and Jimmy Heath’s attention to US racial strain, the pictures mix formal elegance with civic mindfulness. Heath’s “2001 Uprising” I and II punctuate the theme by evoking a troubled history of race relations in Cincinnati, documenting protests against the violent and sometimes deadly policing of the city’s African American population. While the first image contrasts officers in riot gear with a citizen raising a portrait of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Malcolm X, the second laments failed communication between activists and law enforcement. “Uprising II” includes an officer’s back in the foreground while demonstrators make dramatic, pleading gestures in the distance. Although the policeman faces the protesters, he turns his back to us, creating a sense of intransigence or indifference. Anguished faces in the crowd intensify the impression. The standoff produces powerful signals of frustration, of public alienation from unresponsive authority figures. Given that the show coincides with the trial of Ray Tensing, the white University of Cincinnati patrolman who killed African American Samuel Dubose during a traffic stop, Heath’s photo sounds a cautionary note not only about unchecked violence against citizens, but subsequent refusal to engage the community in dialogue. At such moments, the show reaches beyond the question of how photos speak to what kinds of speech they promote.

As the photographs call for tough conversations, they cloud the distinction between form and content, making their pleas through framing and composition as much as subject matter. They create meaning both from bodies in space and from those bodies’ positioning relative to each other. That meaning ranges between sensuality and fear, amity and antagonism. At times those bodies find themselves overwhelmed by the landscape or built environment; at others, they draw affirmation from it. Sometimes people are nearly indistinguishable from the background, while other times crisp forms push forward from fogs of color. Epistemologies and political insights rarely inhabit figure or ground alone but derive from relationships between the two. Those relationships convey some of the distinctive perspectives among people with disabilities, young people, and Cincinnati photographers both seasoned and new, all of whom advance the gallery’s mission of testing artistic and social boundaries. Whether the images depict Cincinnati in explicit fashion or display the gifts of its inhabitants, they reflect the cultural mosaic that gives the city its vigor and soul. They also reflect the vast prospects of a gallery on the cusp of its second decade, its next sixty shows.

The “PhotoSpeak” exhibition ran though November 11, 2016. Art Beyond Boundaries is located at 1410 Main Street, Cincinnati, OH, 45202.

–Christopher Carter is an associate professor and Composition Director in the English Department at the University of Cincinnati. He is the author of Rhetoric and Resistance in the Corporate Academy (Hampton Press, 2008) and Rhetorical Exposures: Confrontation and Contradiction in US Social Documentary Photography (University of Alabama Press, 2015).

[1] Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke UP, 2010.