When I was 25, I had the good fortune to experience “The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890-1985,” one of the most ground-breaking painting exhibitions (accompanied by a mind-blowing catalogue) ever assembled, at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where “Another World: The Transcendental Painting Group: 1938-1945” is currently on view. These exhibitions are related, since four of the eleven artists featured in the second LACMA show, curated by independent curator Michael Duncan, were included in the first show some thirty-six years ago.

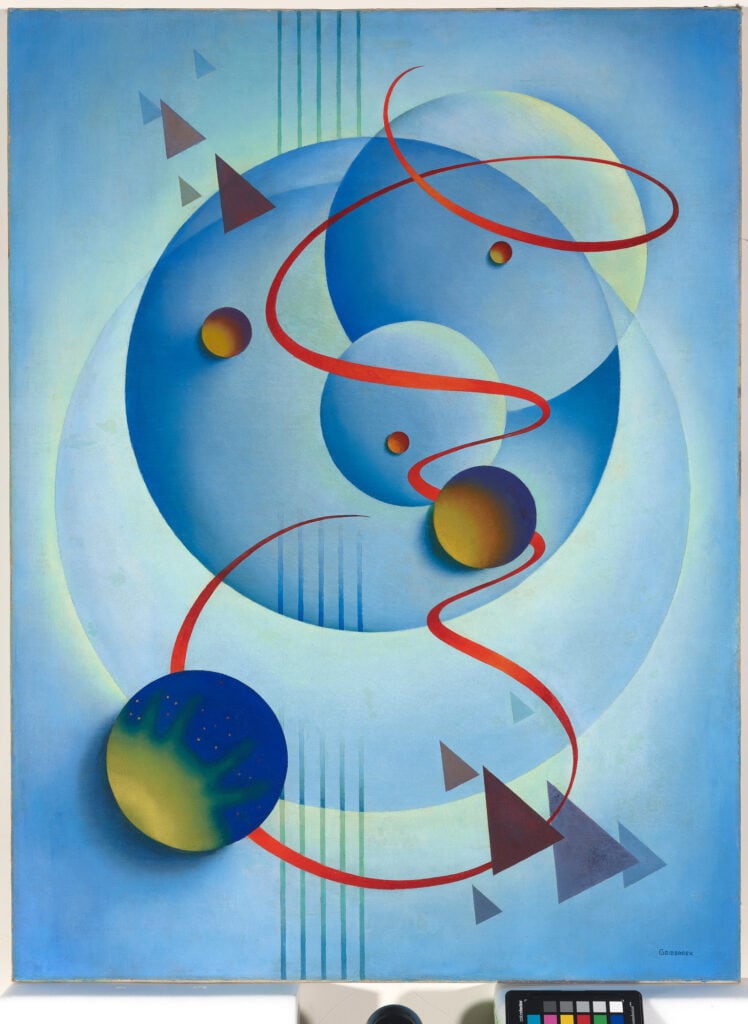

While working on my essay for Stewart Goldman’s Art Academy of Cincinnati catalogue, I kept thinking about the Transcendental Painting Group (TPG), but I had yet to visit this exhibition. Goldman’s approach is “transcendental,” since his paintings tend to explore what lies behind each scene: under bark, behind walls, or in people’s thoughts. Similarly, TPG’s 1938 manifesto championed paintings that go “beyond the appearance of the physical world to new concepts of space, color, light, and design, to imaginative realms that are idealistic and spiritual.” Although TPG paintings are largely geometric, tranquil, and far tidier than Goldman’s remarkably energetic style, they share his paintings’ capacity to rapidly shift perspectives like a bumblebee in flight and to transport audiences to realms beyond immediate perception. Consider how the twisting ribbon-like form in Robert Gribbroek’s painting Composition #57/Pattern 29 (1938) loops our eyes down and around and up and around again, causing our perspective to shift mid-sight.

Invited by Josef Albers in 1937 to join the American Abstract Artists, the Santa-Fe-based Raymond Jonson opted instead to galvanize a local cadre of “transcendental” painters. Despite his skill at depicting western scenes, Johnson thought art ought to convey “the wonders of a richer and deeper land –the world of peace– love and human relations projected through pure form.” TPG members credited their largely abstract imagery to Helena Blavatsky’s Theosophical ideas, Wassily Kandinsky’s book Concerning the Spiritual in Art (1910), and perhaps most importantly to recent scientific discoveries, yet they rejected any connection to Ralph Waldo Emerson’s 19th century “transcendental” philosophy, which they found overly pantheistic.

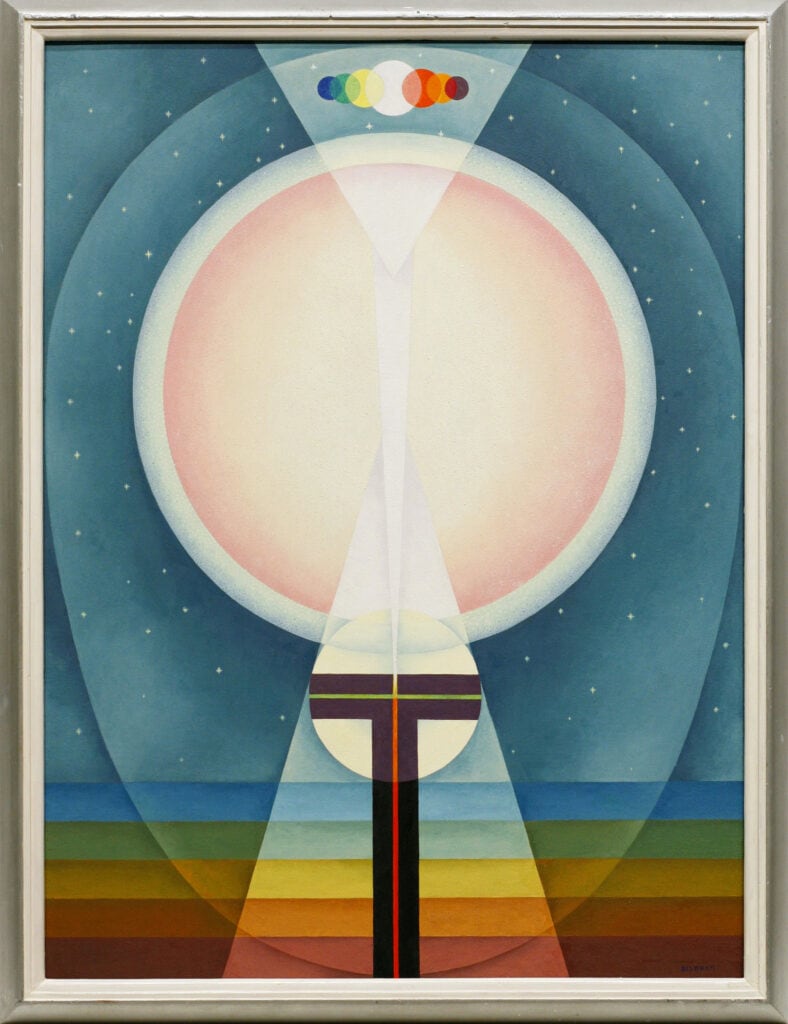

Emerson prevailed upon painters to “give us only the spirit and the splendor;” since what the artist “sees through his eyes is seen in that spectacle; and he will come to value the expression of nature and not nature itself, and so exalt in his copy the features that please him.” Had he written “the divine” instead of “nature,” their views might have cohered. Even so, Emerson’s interest in Eastern religions, western esotericism, and occultism is said to have paved the way for Blavatsky’s views, which Annie Besant developed further after her death. Exemplary of Theosophical mysticism, Emil Bisttram’s Oversoul (1941) captures Theosophy’s notion of “evolution in two directions,” such that the physical ascends to the spiritual world and the divine descends to the material world. The “T” itself is likely a reference to “transcendental,” “Theosophy,” or “Taos” (where he had been living since 1931). The circle refers to the cosmos; and the varying colors potentially reflect Besant’s designating particular meanings to colors as she articulated in her essay “Meaning of the Colours,” published in Thought-Forms (1941).

Apropos Bessant’s color charts, TPG-member Florence Miller Pierce deployed blue to convey religiosity and white to express incandescence or enlightenment, since life itself is envisioned as the very “beneficence of light.”

In addition to paintings by Bisttram and Miller Pierce, “Another World” features her husband Horace Pierce’s posthumous video (conceived in 1938, yet edited in 2020 by Gina Lamb and depicted in the installation shot above), Agnes Pelton’s 1936-1939 sketchbook plus 61 paintings and 24 drawings by 6 TPG members and their associate Dale Rudhyar, the composer/painter who first proposed the term “transcendental.” Rudhyar’s unpublished manuscript The Transcendental Movement in Painting (1938) particularizes TPA as distinctly American.

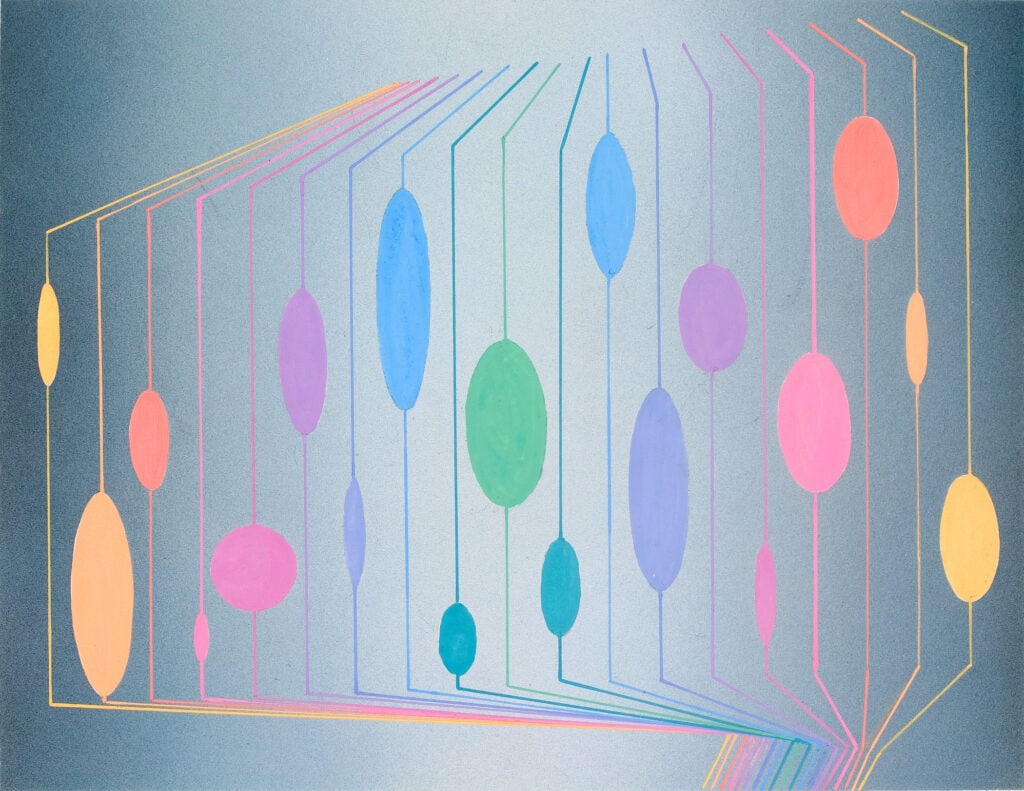

Despite its modest membership, these artists contributed mightily to American culture: Bisttram opened art schools in Taos, Phoenix, and Los Angeles, Lawren Harris and Jonson taught at Arsuna School of Fine Arts in Santa Fe, and Jonson also taught for 20 years at the University of New Mexico; William Lumpkins opened architecture firms in Santa Fe and La Jolla; and Gribbroek worked in Hollywood on and off. TPA members hopped between the various avant-garde communities inhabiting Taos, Santa Fe, New York City, and Los Angeles. In light of its hard-edge, layered, translucent shapes, Jonson’s Oil No. 9 suggests an intense light shaft illuminating a flickering flame that capably splits visible light into multiple blue and green panes.

By contrast, Horace Pierce’s interest in film inspired drawings such as Symphony #2, whose colorful ellipses in varying heights dynamically capture its sense of musicality.

Following Stuart Walker’s death in 1940, TPA’s joint efforts started to dwindle, yet most managed to have solo exhibitions during and after WWII. In 1941, Lumpkins and Gribbroek departed for war-related positions, while Ed Garman was drafted into the Navy in 1942 and Pierce was drafted in 1944. They didn’t exhibit again as a group, however, until 1982.

A household name in his native Canada, Harris lived only briefly in New Mexico, before moving to Vancouver, his move to Santa Fe cut short by the war. Harris was apparently the most “versed in Theosophical thought,” yet his paintings feel strangely freer, and far less meticulous.

Despite their numerous exhibitions and retrospectives over eight decades, only Pelton has managed to achieve name recognition in the U.S.. Traveling to five museums, “Another World” aims not only to reappraise the significance of “spiritual” artworks, which curator Michael Duncan claims the nihilist contemporary artworld fails to take seriously, but to raise the visibility of TPA’s contribution to American abstract painting, though not all TPA paintings are abstract. Pelton’s early pastel drawings inspired by visits to New Mexico in 1918 and 1919, as well as the black and white birds in her painting Winter (1933) are distinctly figurative, as are several Gribbroek paintings, such as Untitled (Poppy) (1938) and Beyond Civilization to Texas (1950).