Thanks to the generosity of the Primas Family Collection, visitors to the Cincinnati Art Museum’s exhibit, Charles White: A Little Higher, can experience powerful artworks created by one of the most influential African American artists of the twentieth century. Over a forty year career, the Chicago-born artist and educator, master draftsman, printmaker and painter interpreted the Black experience.

White had a life-long commitment to social justice and equality. The forty-six works in this exhibit are artistically powerful figure studies that beautifully capture faces and human figures. There are evocative works that celebrate Black experiences. White stated, “I like to think that my work has a universality to it. I deal with love, hope, courage, freedom, and dignity—the full gamut of the human experience.”

But White’s artworks are also emotionally powerful. The prints, charcoal drawings and paintings are testaments to his crusade to illuminate shameful events in American history and the cruelties of racism and oppression. Be prepared for raw emotions in portraits and narrative works: for anguish and defeat, for anger and longing in men, women and children caught in dehumanizing situations.

The exhibit is on view in three galleries on the first floor. You’ll want to start in Gallery 125 near the café where you’ll find a timeline of White’s life in the center of the room. Photos illustrate key events in his life. White’s dedication to social justice might have begun early with family stories. He was the grandson of a slave who was impregnated by her master eleven times. When he was in high school, two art academies rescinded scholarships once they found out Charles White was Black. Despite that he went on to study at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, work for the Works Progress Administration, serve in WWII and teach at universities and exhibit at galleries across the country.

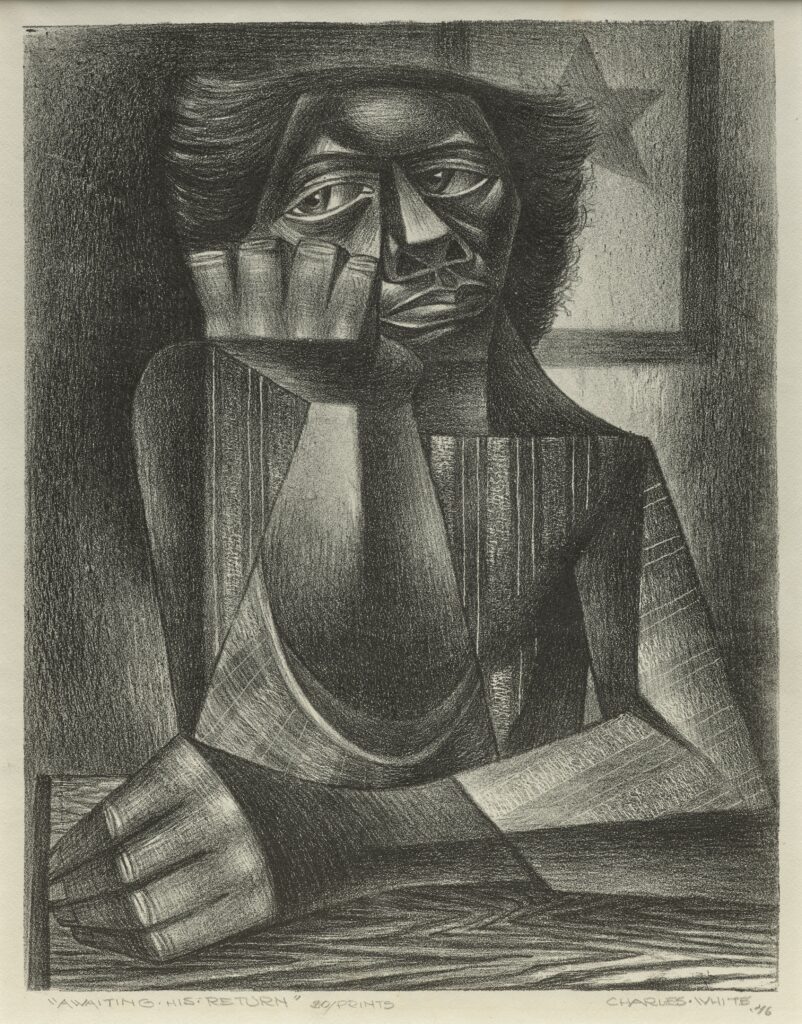

On the back wall of the timeline, to the left, is one of White’s early prints. It honors the Black mothers whose family members served in the military. We don’t know the color of the star on the flag in the background. If it was blue, their son, husband or brother was alive. If it was gold, their loved one had died in service to his country. The angular lines and deep tones, the work-worn hands, all communicate grief to me. Next to the label is a poem by Ryan Nichole Leary, local artist and educator. It’s part of the Community Voices project, which features written responses to White’s key works in the exhibit. Take the time to read them for a fuller experience of the artworks.

To the left of the timeline is a commanding four foot tall linocut of the Biblical prophet, Micah. We look up at this monumental figure pulsing with energy flowing from robes full of jagged lines and swirling dark hair and beard surrounding a chiseled face. Moving purposefully forward and looking far ahead with hands clenched, Micah gazes into the distance or perhaps the future. White was a friend of many civil rights leaders, including Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., many of whom drew inspiration from Micah’s spiritual convictions in their campaigns for social justice, equity and universal enfranchisement.

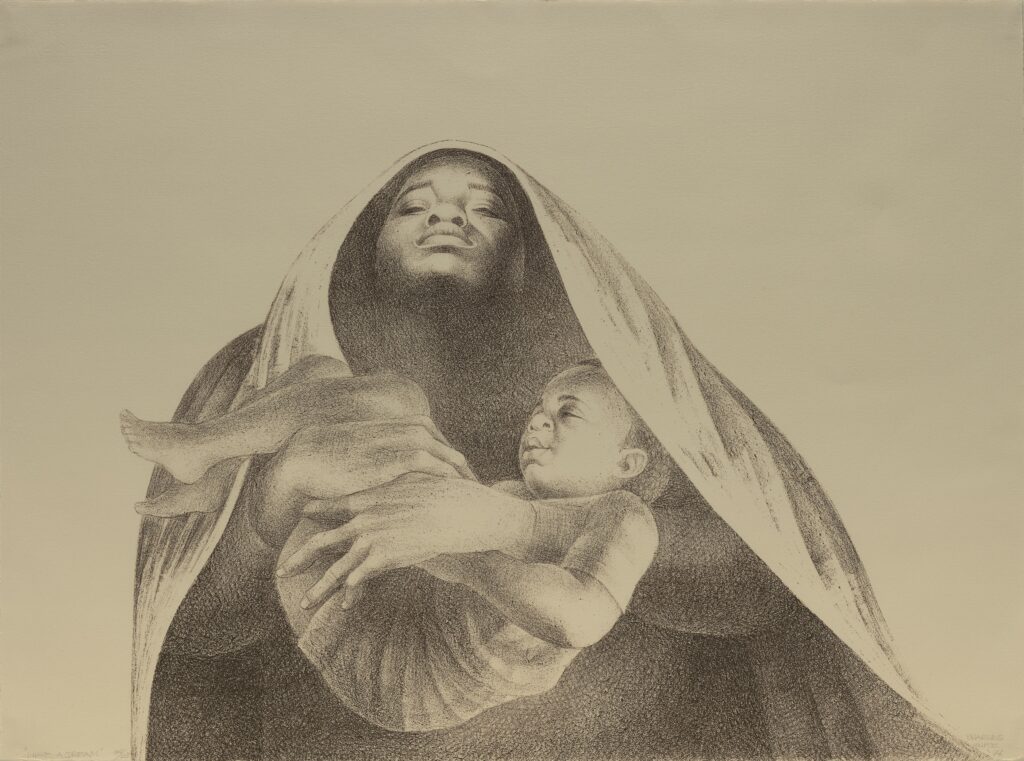

Roughly chronologically, move from Gallery 125’s works from the 1930s-1960s to Gallery 124, representing the 1960s-1970s. Walk to the right where a large lithograph, I Have a Dream, will catch your attention. A mother cradles her child, both enveloped in a protective cape. Her face is upturned, her eyes closed, her expression enigmatic. What is she thinking? Is she weary, hopeful, contemplating the past, praying for a better future? White celebrates the strength and power of Black women, three years after Martin Luther King, Jr.’s plea for equity, dignity and respect for all.

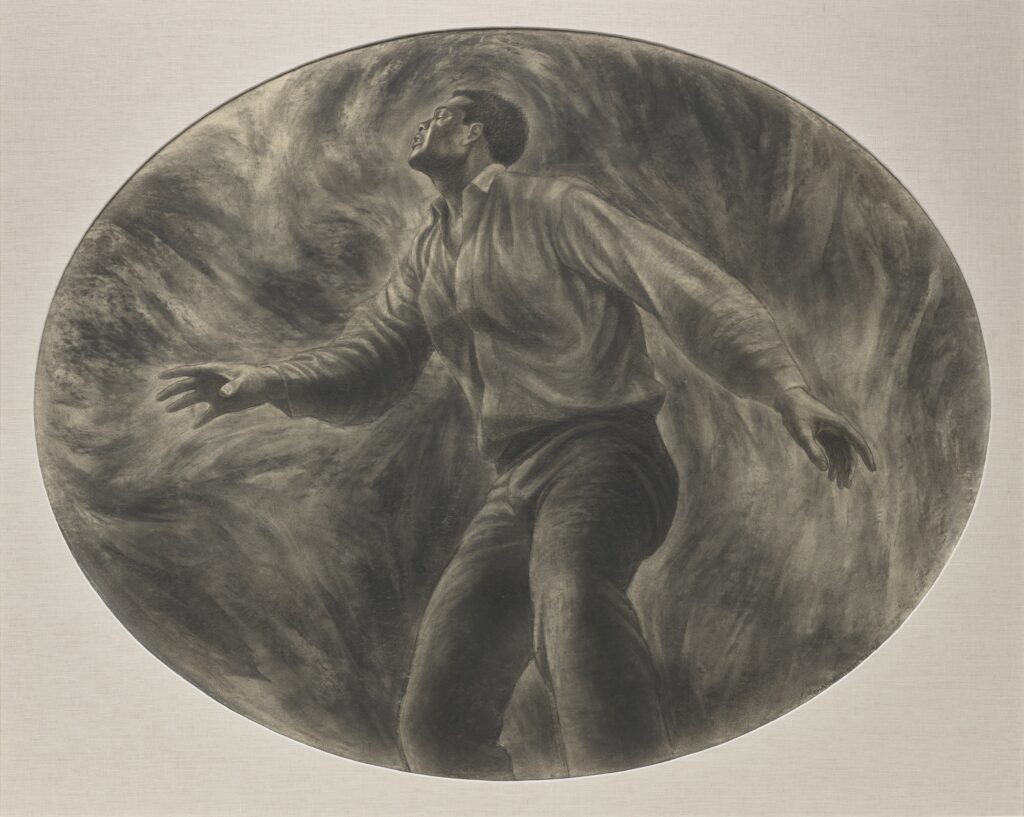

The inner wall of Gallery 124 is dominated by J’Accuse #6 (I accuse). Through a masterful use of tints and shades of black charcoal, White creates a dynamic figure. Is the man dancing or struggling, moving forward or running away, in a haze of fog or fire? You interpret it. Through the image and title, White connected systemic racism in the United States to a notorious example of government corruption and antisemitism in France. See the label copy next to the artwork for details. The artist pointed a finger at perpetrators of hate and injustice. This was the time of the Civil Rights movement, the Freedom Riders and Birmingham church bombings.

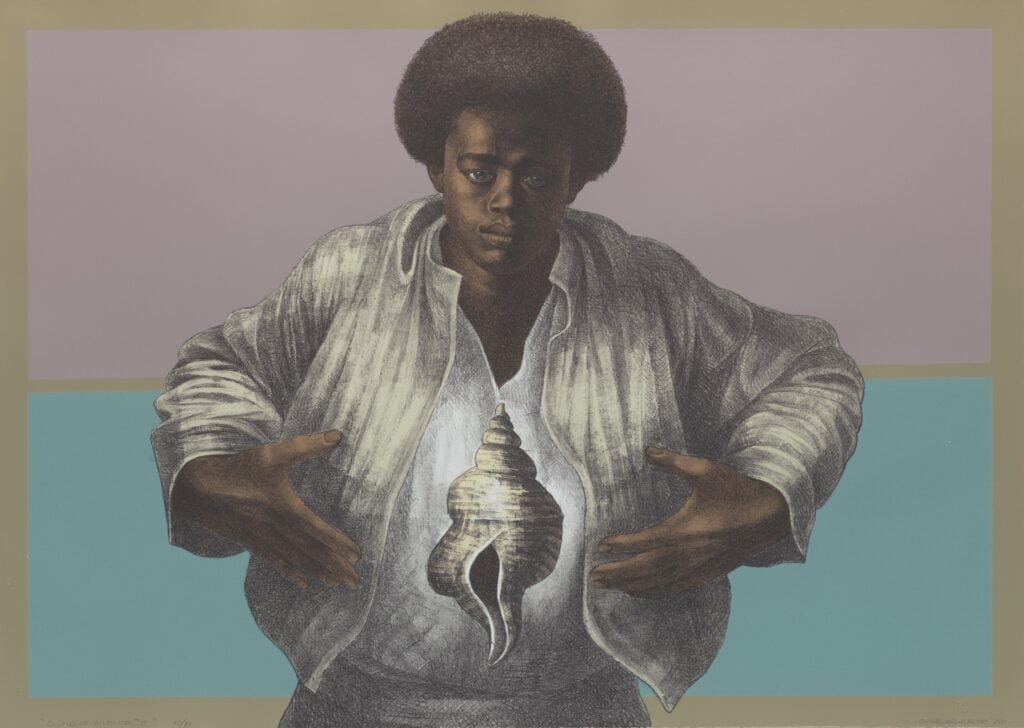

In the later years of his career, White added color to many of his images. Sound of Silence II might have a number of interpretations. Who is the handsome young man gazing steadily at us? Why has he pulled back his jacket to reveal a luminous white spiral shell that seems to float towards us? Does this refer to Simon and Garfunkel’s song? Don’t let the silence swallow an important message? Or does it echo African nkisi nkondo figures which centered power and energy in the abdomen? Will this young man make a difference in the world? What is your interpretation?

Continue your tour in Gallery 123, where a group of twelve oil-wash illustrations is on public display for the first time. The Johnson Publishing Company commissioned White to create the artworks for the landmark book The Shaping of Black America (1975) written by the noted author and Ebony magazine editor, Lerone Bennett, Jr. The wall panel describes the project as “a summary of White’s commitment to communicating with the public about the legacies of racism and oppression, the nobility and aspirations of ordinary people, the heroes who fought for freedom and equality and the accomplishments of Black Americans.”

The illustrations appeared in the book as chapter introductions, starting with The First Generation (The Arrival) depicting the sale of the first slaves in 1619. Here a stoic shackled woman, as in all the illustrations, is carefully rendered as a living, breathing person, in sepia tones against a background meant to appear as folded worn parchment. Other chapter headings (given here in parentheses) feature well-known figures such as Harriet Tubman (The World of the Slave) and Frederick Douglass (System). Others might not be as well known, such as Rev. Richard Allen and Captain Paul Cuffe (The Black Founding Fathers). Other figures are representative, such as The Black Worker and the collage of African and Indigenous peoples (Black and Red).

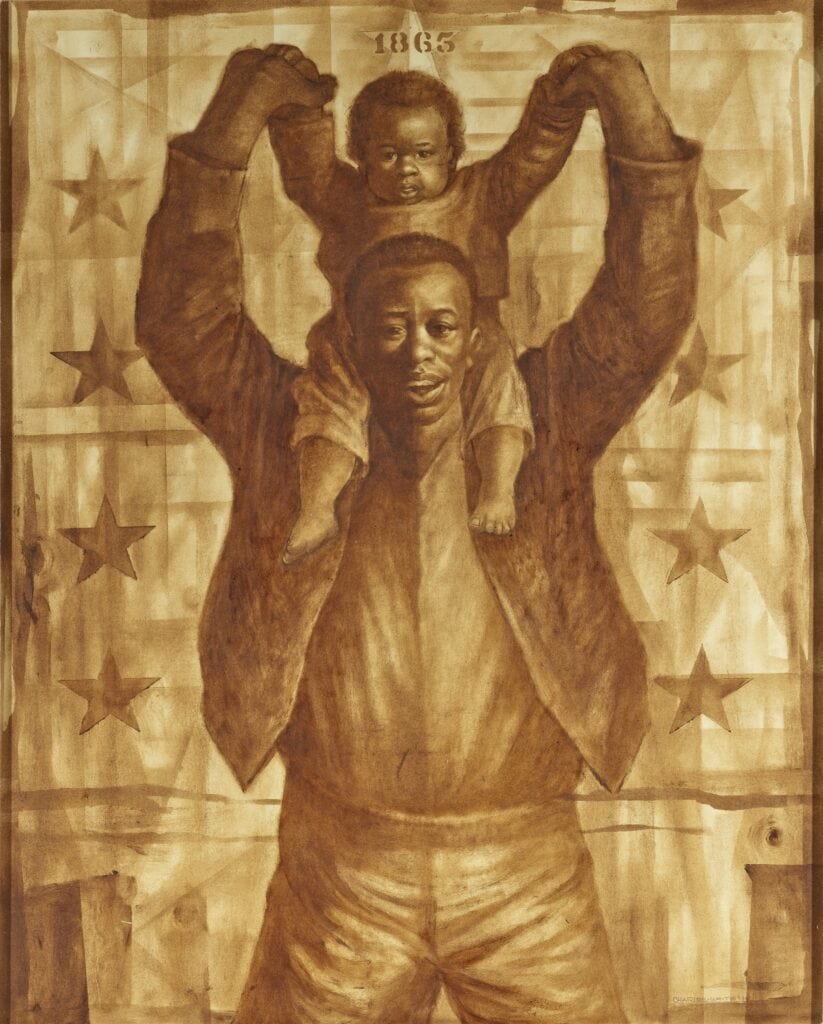

Your tour ends with the expressive Jubilee. A joyous father hoists a toddler on his shoulders against a background of stars. The date 1865 appears above two figures. That was the year that General Order No. 3 liberated the enslaved people of Texas, the last holdout in the South. The father appears to be walking towards us, toward freedom, toward a better future. This impressive image is a fitting tribute to the artist Ebony magazine named “The Portrayer of Black Dignity.”

This is just a sampling of the thoughtful, illuminating and powerful artworks on display in Charles White: A Little Higher. They will challenge and perhaps inspire you, as will the poems, raps and spoken word pieces in Community Voices that accompany seven of the artworks.