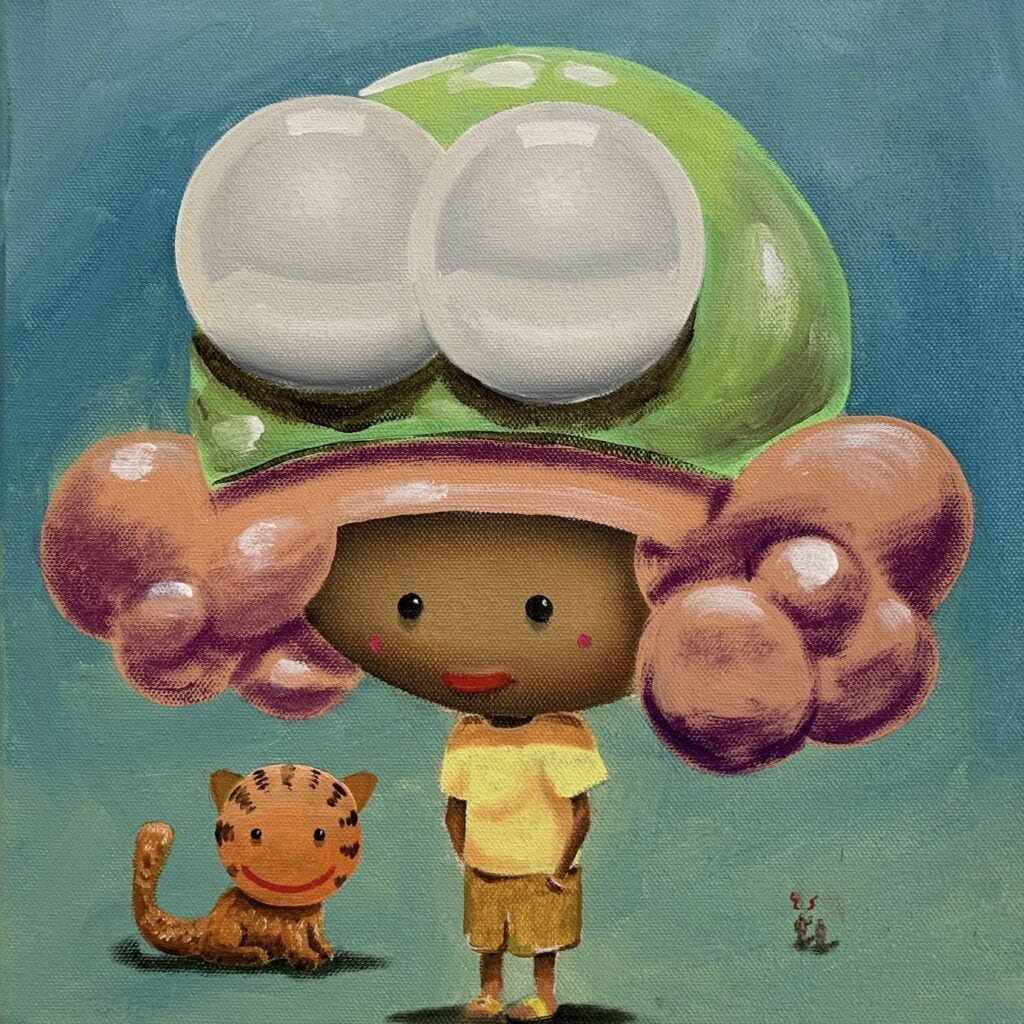

David Kaye is a veteran artist—not in the sense that he is an artist who has been toiling with the canvas for many decades but insofar as he is an artist who began making work while touring as a member of the United Kingdom military. His work, albeit painted with a post-Pop Art, Yoshitomo Nara-esque air, is directly tethered to these experiences and far more critical in spirit than most all his contemporaries who paint with such bearings. Kaye casts a diametric opposition between subject and style, which I find most curious about his work: on an initial glance, these are inviting and whimsical paintings, rife with portraits of young, doe-eyed saplings seated before smooth, even-toned palettes. But there are cracks that seep through such conviviality, revealing themselves only upon more examined viewing. These fissures indicate the harrowing themes Kaye is truly concerned with, his use of wide-eyed, unsuspecting and unmalicious children in the place of soldiers rife with political commentary. But rather than unspool his critique head-on, Kaye achieves this through subtle, hidden fixtures in his work.

In one painting, for instance, we see what appears to be a tan-skinned young girl squatting on the ground. A charcoal-black cape, tied in the bow of an ascot, drapes over her cardinal-red shorts; her bright, navy-blue shirt reveals a small, bubbling stomach and folded fingers, knuckles tensed. Concessions of the uncanny thus already creep in and as we gaze further up, we see that her crimson lips, painted as a short horizontal stripe, are arced into the shape of a frown. Her eyes are carbon-dotted and blank, her face crowned by a military helmet fitted with goggles from which tufts of curly hazel-chestnut hair protrudes. The painting is fitted with two small details that one might readily glaze over: by her lower-right knee is a perched bird sporting an orange pumpkin-like head. The bird’s lips are painted with the same cherry-red cartoonish stripe and dotted-black eyes as the girl but offers a beaming smile. This is a counter to her scowl, the bird indicating the possibility of flight and escape. Further down, towards the lower-left of the canvas, are three figures—minute and easy to miss. These appear to be plastic toys, the middle one being a jet-black toy soldier with its arm raised in a salute; to its right is a beryl-green toy dinosaur and to its left another, identical toy soldier smaller in size. These index the projected ideation of the military ethos which myriad children grow up with in the form of toys, cinema, and literature.

To better understand Kaye’s intentions and the form of his overall critique, we ought to also consider his biography. Kaye was a solider who, during a tour in Afghanistan with the British Army, turned to art as a form of escape. Although details around his time with the military are scarce, he often indicates that his painting practice has facilitated a means of making sense of his experience as a soldier. He even terms it “therapeutic.” The history of art is, indeed, rife with soldiers making work during their conscriptions so as to better understand their positionality. There is, in fact, an entire genre of art called “trench art”, an evocative albeit somewhat misleading term that describes a wide variety of media (including painted bullet shells and sketches etched into military notebooks/journals, helmets, shrapnel, and planes). Soldiers have often decorated their militaria with prismatic figures, often times steeping them in narratives that mirror their own. The production of such narrative objects is, seemingly, a widespread human response to the conditions of warfare, one that we see shared by soldiers, prisoners of war, and civilians—especially during the First World War (1914-18) and the succeeding inter-war period (1919-39). The various symbolic dimensions include souvenirs and mementoes, objectifications of loss, and war trophies, all of which materialize the relationships between objects, their maker, the warring nations, the living, and the dead. Although Kaye does not paint upon militaria, his thematic concerns undoubtedly invite considering him as part of this storied tradition.

On first glance, Kaye’s paintings appear altogether cheery and cartoon-like. This is a testament to how they instrumentalize his mode of critique. It is only when we examine the tucked figures of symbology closely that we begin to unveil Kaye’s figuring as two opposed poles: one being the narrative of a young soldier who is told to be fighting for their country’s national security whilst guarding the meek; the other being the experience of the enlisted—a brute, alienating, autonomizing reality of violence that dovetails with the State Department’s financial interests. This is, of course, why so many veterans and organizations like “About Face” speak critically of the military and its surreptitious devices.

Kaye’s work has a number of stylistic compatriots. For instance, Javier Calleja’s loose-eyed figures of bulbous children may come to mind. But Kaye’s paintings unravel critique unique to his blue, wary soul. Calleja’s use of children may figure the uncanny, but the uncanny for Calleja serves as an end in itself. In Kaye’s case, children donning pilot helmets, index the age when many are conscripted or choose to join the military in hopes of attending university or achieving financial independence. This is particularly common in the United States amongst lower and lower-middle class families who cannot afford to pay their children’s college tuition.

Kaye paints with a kind of cartoonish mastery—one cultivated from years of ardent comic readership, his style being that of Tintin-meets-Pop Art. The cartoonish face of his child soldiers is racking, but such racking is the business of the assiduous artist. That Kaye achieves his critique with an inviting style, accessible to all, is a testament to his dexterity. Kaye is an emerging artist who has nevertheless already exhibited widely, with his work quickly garnering attention from international galleries and collectors, alike. His most recent solo exhibitions include Nych gallery in Chicago and Gallery ovo in Taipei. I am curious to see how Kaye furthers his mode of critique in his forthcoming work.