Although most attribute the word “ecology” to 19th century German naturalist Ernst Haeckel, Lucy Lippard attributes the term to Ellen Swallow Richards, who coined the word from oikos (pronounced “ekos”), the Greek word for home. “Ecology” turns out to be the “study of home.” Given the tendency for plants and animals to migrate, whether forcibly (carried by the wind) or voluntarily (seasonal habits), “home” is a rather fraught concept. Human beings, no different than Red Maples, Bald Cypresses, Monarch butterflies, elk, wildebeest, flamingos, or zebras, are constantly on the move, enabling old habits to inhabit new habitats.

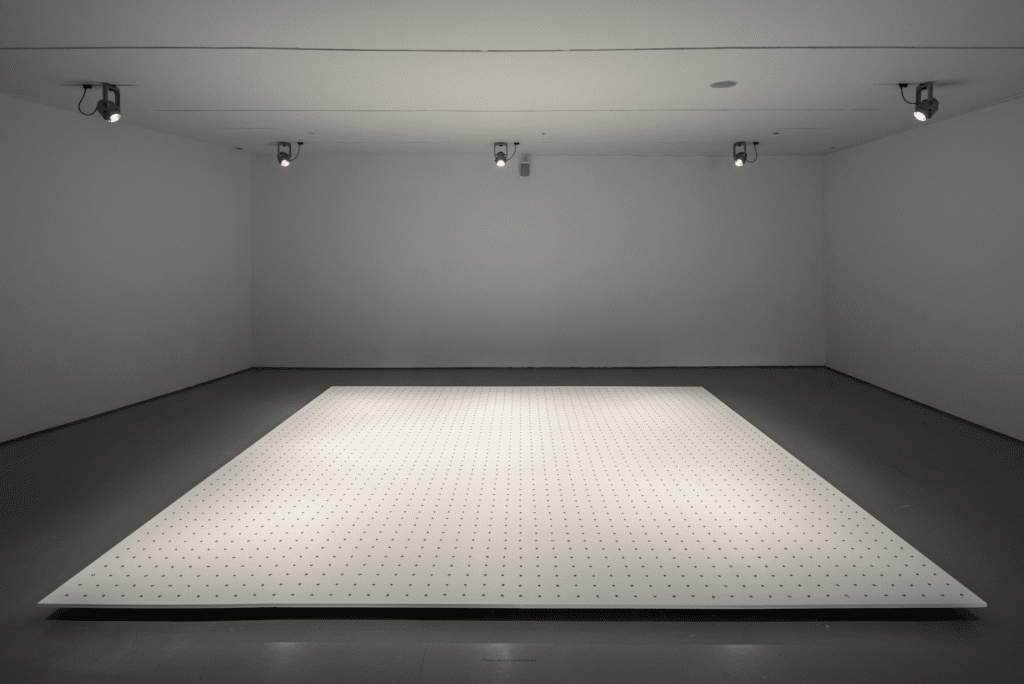

By focusing on artworks by artists whose ancestors’ lives were forcibly uprooted as a result of colonialism and slavery, “Ecologies of Elsewhere” draws attention to the way memories tied to botanical migration inevitably shape culture. Just as colonizers transported technologies, traditions, and species to/from distant lands, slaves exported technologies, traditions, and species wherever they landed. During Sammy Baloji’s three-channel video Pungulume (2016) (presented here as a single channel in the black box), Sanga chief Mpala describes how colonizers redrew cultural boundaries and then set up extraction industries to mine copper, further dismembering his ancestral homeland. Kapwani Kiwanga’s Semence (2020) displays 16,000 tiny ceramic rice grains atop a massive white platform. Piled in groups of seven and situated 10cm apart, much like a newly planted rice paddy, the seeds are enveloped by a recording of someone reciting a poem translated into isiXhosa. Semence thus credits “rice-coast” slaves with having exported two technologies; Oryza glabberima, which West Africans domesticated around 3000 BC, as well as the specialized knowledge of how to cultivate this red rice.

Courtesy of the Kapwani Kiwanga and Goodman Gallery

Photo: Wes Battoclette, 2023. Image courtesy of the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH.

The video Foodtopia: Después de todo territorio (2021) by Las Nietas de Nonó, two Puerto Rican sisters living in Barrio San Antón east of San Juan, follows the sisters as they search their industrial neighborhood for plantains, crabs, coconuts, edible herbs, and other wild fruits during the COVID-19 lockdown. In preparing and cooking their foraged bounty over fire, they revitalize ancestral techniques. By contrast, the photographic installation In Transit (2018/2023) by Hawaiian native Emily Hanako Momohara, whose grandparents immigrated from Japan to Hawaii to work in agriculture, memorializes yesteryear’s prized pineapple. Following the islands’ post-war transformation from sugarcane to pineapple plantations, Hawaii produced some 75% of the world’s pineapples at its peak, yet tourism has since displaced agriculture. Food is hardly the only thing that boosts human wellbeing. Other artists explore plants’ healing properties. In capturing ancestral spiritual practices surrounding cotton, Lisandro Suriel’s astonishing photographs that border on fashion photography reinvigorate African magic as a source of control and fear. This exhibition’s only living sculpture, Rashid Johnson’s Untitled Stranger (2017), is a black steel ziggurat-like plant stand housing palm trees and other tropical plants alongside books of interest and discrete objects containing black soap and shea butter, materials revered by some Africans and their descendants for their healing properties. The antibacterial soap, whose customary color is derived from plant ashes such as burnt cocoa pod or roasted plantain skins, contains shea butter, an edible fat extracted from the nut of the African shea tree, and/or palm kernel oil, though not lye (NaOH).

With Zheng Bo’s video Pteridophilia (2016), we witness frolicking boys engaged in an interspecies mélange à trois with Taiwanese ferns, described as an “under-appreciated” species. The fern’s lowly status likely stems from its ubiquity, since Taiwan, known as the Kingdom of Ferns, boasts 650 fern species, representing 34 of 39 fern families. Elsewhere, he exhibits one of his Manuals for Survival (2016), for which he hand-copied Taiwan’s Wild Edible Plants (1945). Created to avert starvation during an enemy occupation, its original creator identified 103 forageable plants. Surprisingly, each plant’s Latin name pops up amidst Chinese characters. Longing for rootedness and belonging, other artists capture their former homelands’ exquisite beauty. Abel Rodríguez, an elder from the Nonuya ethnic group that live near the Cahuinarí River (a river in the Amazon River Basin), has been drawing his ancestral homeland from memory ever since he went into exile in the 1990s. Displaced by FARC (Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia) and extraction industries, his drawings preserve his vast knowledge of the Nonuya region’s flora and fauna, about which his uncle, a sabedor (man of knowledge) taught both Rodríguez and ethnobotanists whom he guided through the jungle.

Photo: Wes Battoclette, 2023. Image courtesy of the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH.

Similarly, Lorena Molino installed dozens of images and videos publicizing her native El Salvador’s diverse ecosystems mixed with references to that nation’s textile industry.

Photo: Wes Battoclette, 2023. Image courtesy of the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH.

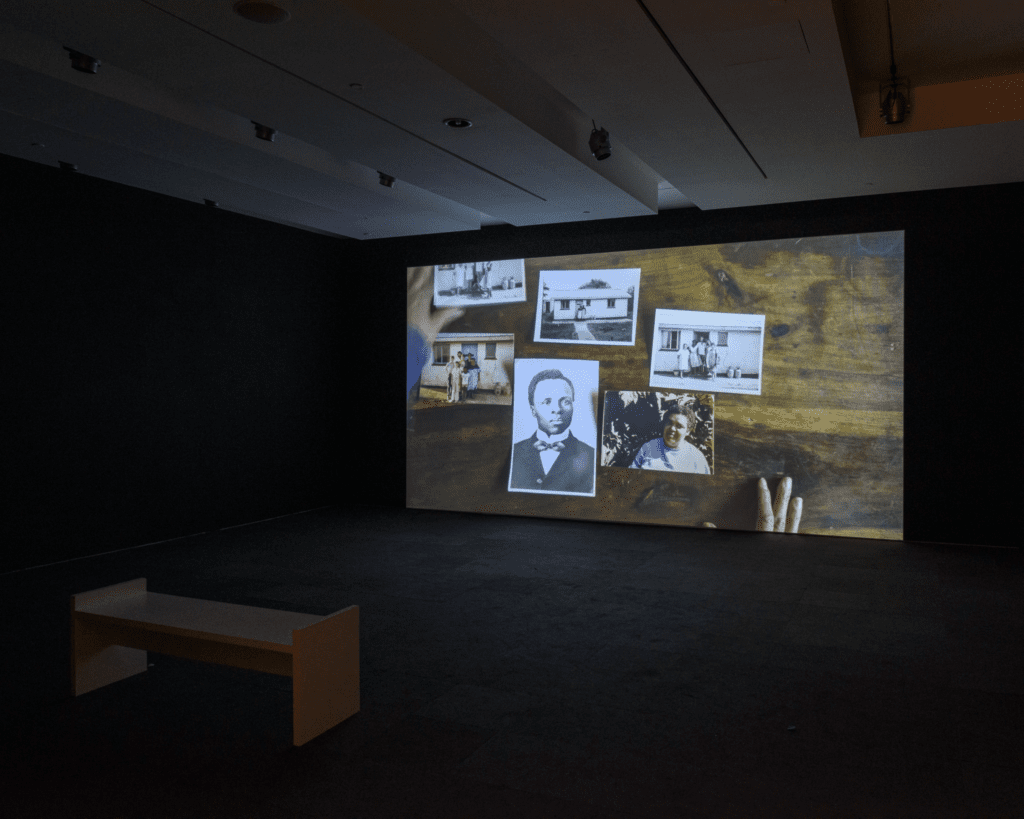

Ilze Wolff’s video Summer Flowers (2021) pays tribute to South African activist gardener/author Bessie Head (1937-1986), whose first novel When Rain Clouds Gather (1968) connected colonial interference, politics, and gardening practices and afforded her the opportunity to purchase a garden-home while exiled in Botswana.

Courtesy of Wolff Architects, with permission from the Bessie Head Heritage Trust and the Khama III Memorial Museum, Serowe

Photo: Wes Battoclette, 2023. Image courtesy of the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH.

Firelei Báez’s Everything I Know About Love I invented (Titus’ atlas of Hamilton County) (2023) found inspiration in liner notes accompanying Detroit electronic duo Drexciya’s 1997 album The Quest that identified Drexciya as the name of an underwater nation housing the unborn children of pregnant African slaves thrown overboard at sea. Underlying this large-scale portable mural’s vibrant waves is a portion of the 1860 Underground Railroad map. Once used to usher slaves to freedom, this map centers on Farmers’ College in nearby College Hill.

Less obviously tied to botanical migrations are paintings by Torkwase Dyson and Michaela Yearwood-Dan and Rachel Youn’s installation of kinetic sculptures spinning artificial plant parts, simulating a dance party. Since plants really do dance in the dark (Frankfurt’s 431art has recorded plants blasting ultrasound squeals in the 20khz-100khz range), it might have been more interesting (and mind-blowing) to experience an actual party of dancing plants as art.

No doubt, people will enjoy the opportunity to socialize seated in MADEYOULOOK’s garden, adjacent the 6th Street entrance.

“Ecologies of Elsewhere” is on view at the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati through August 6, 2023.