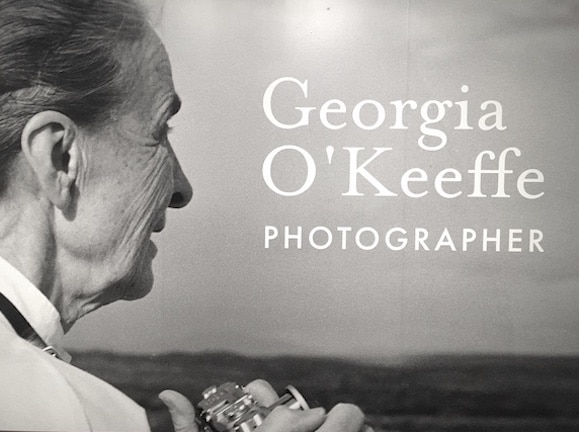

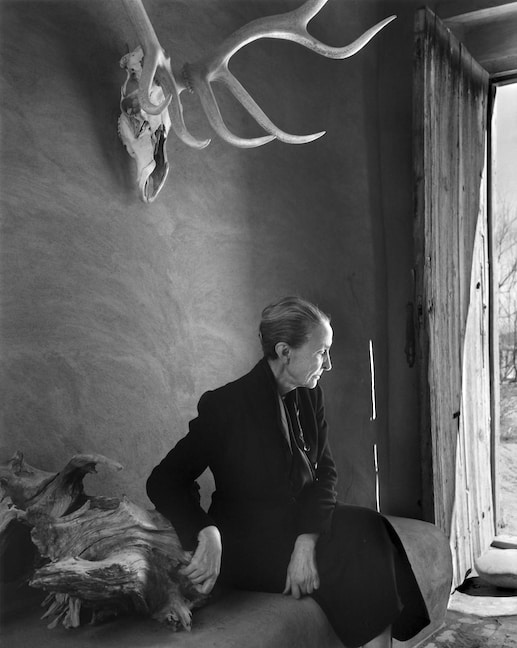

(Todd Webb, Georgia O’Keeffe with Camera, 1959, printed later, inkjet print,

Todd Webb Archive. © Todd Webb Archive, Portland, Maine, USA)

The first major exhibition of 2023 to open at the Cincinnati Art Museum presents a comprehensive selection of nearly 100 photographs made by the celebrated painter and feminist icon, Georgia O’Keeffe. Its title, Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer, is also the title of a substantial, $80 book published by the Museum of Fine Arts Houston and Yale University Press. The exhibition itself is a collaboration between the MFAH and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, NM, having opened in Houston in 2021 and since traveling to the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts, and the Denver Art Museum and Cincinnati. (Interestingly, at the Addison, it opened alongside “two other presentations meant to contextualize O’Keeffe’s photographs: ‘Arthur Wesley Dow: Nearest to the Divine,’ which brings together the work of O’Keeffe’s initial and influential art mentor in New York; and ‘What Next?: Camera Work and 291 Magazine,’ a collection of images from two seminal photography journals, compiled to offer a snapshot of the artistic scene surrounding her and Stieglitz.”). This visit to Cincinnati marks the end of its tour.

At the CAM, the exhibition has nearly 100 photographs (although several fewer than in Houston), plus an additional photograph from the CAM collection: the 1956 portrait of O’Keeffe by Yousuf Karsh. There are also 11 original paintings and six drawings by O’Keeffe peppering the exhibition.

Perhaps provoked by its title, the exhibition has been described (repeated in Cincinnati Magazine) as “the first major investigation into [O’Keeffe’s] 30-year photography career.” Let’s stop right there. There was no “photography career.” Georgia O’Keeffe wasn’t a photographer. She did, however, take photographs, a fact which is not without interest.

The exhibition and book posit that O’Keeffe “embraced photography as a unique artistic practice and took ownership of her relationship with the medium.” It’s an idea that excites many photographers and others, aware of O’Keeffe’s long association with the older Alfred Stieglitz, the most important figure in the early history of modernist photography and a key figure in America’s introduction to modern art overall. This seemed a chance to see what she could do photographically once out from under the shadow of the Great Man. Perhaps in the 21st century, thanks to better scholarship, people hoped to see her eclipse him in his own medium, ala Freida Kahlo or Lee Miller. Perhaps, as with Charles Sheeler, her photographs would prove even more interesting than the paintings on which many are based.

No such luck for those wishing such things. O’Keeffe the painter is in no danger of being eclipsed by O’Keeffe the photographer. She actually had little interest in the medium and even worked to disassociate herself from photography, despite her years of working with Stieglitz, retouching his prints and installing many of the exhibitions presented at two of his venues, The Intimate Gallery and An American Place. “Stieglitz used to say I knew less about photography than anybody he ever knew,” she told a journalist in 1962. “Yet, he’d trust my judgment of a print.”

As she wrote to a friend and colleague about Stieglitz: “It often sounds as if I was born and taught to walk by him — and never thought of painting till he worked on me.” She resisted acknowledging any impact on her painting from photography (though she did once admit to an interviewer “I must have been influenced by photography. I saw so much of it… I can’t think specifically how. Perhaps the clarity of the print influenced me.”)

Photography, she wrote in 1922, some eight years into her relationship with Stieglitz, did not suffer the same burden of tradition as painting. She saw it (inaccurately) as unencumbered by the history and expectations of genre and style. Usually she referred to the photographs she took as “snaps” not photographs. For the most part, O’Keeffe tucked those snaps into letters to friends.

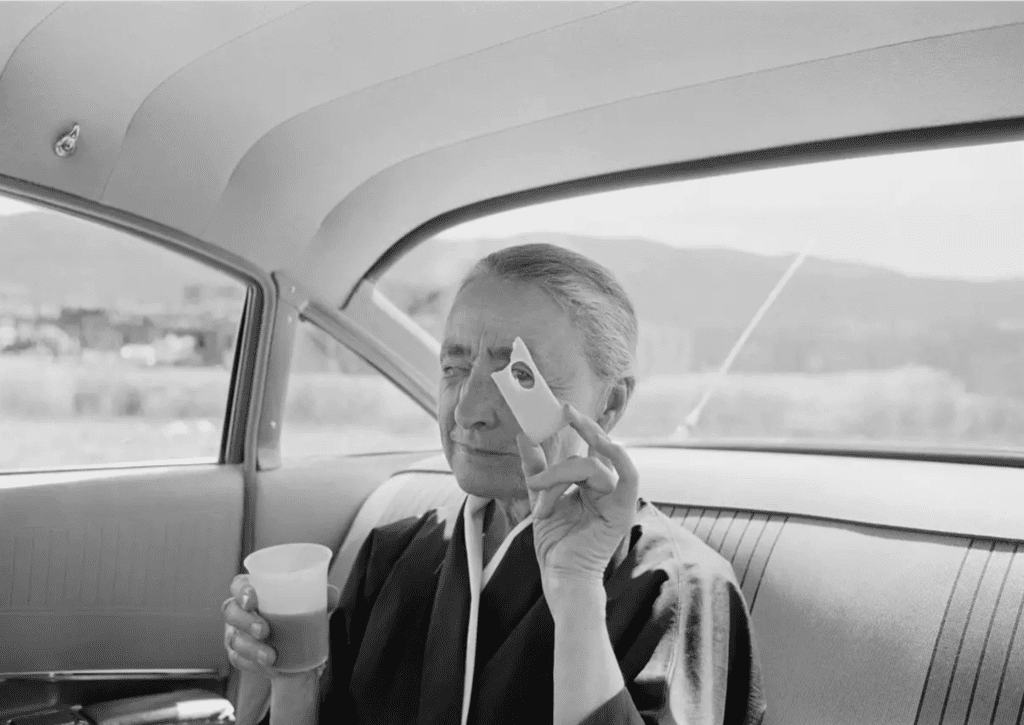

As Ann Daly writes in My Georgia O’Keeffe, she saw the camera as emphasizing the act of seeing rather than the production of an object. At best, I think it can be said that she employed the camera to extend her vision as a painter and provide her with fresh insights. The camera viewfinder and the subsequent photographs were instructive for her, and they can be for the audience of this exhibition and readers of the book. The eye has it. There is a playful photograph Tony Vaccaro took in the back seat of a car, in which O’Keeffe returns the gaze of the photographer by holding a piece of Swiss cheese to her eye, as though looking through a camera viewfinder.

collection Georgia O’Keeffe Museum (not included in CAM exhibition)

She often employed her photographs as notes, or less often “sketches”, to be brought back to her studio, studied and learned from. (A number of the prints were found to have tape residue on their reverse, proposing the images being displayed so as to be encountered regularly.) She wrote to a friend, the journalist Edith Evans Asbury, that she intended them as records.

However, as Daly writes, she had no illusions about the veracity of photography: “Many people think photography is realistic. I think it lies. I am often astonished to see something after I have seen a photograph of it. Often it isn’t accurate. It can be quite a bit different from the real thing.” As the subject of hundreds of photographs by Stieglitz, this would have been manifestly apparent to her.

The CAM exhibition is the result of a five year long labor of love by MFAH’s Associate Curator of photography Lisa Volpe, begun even before her tenure at the museum.

Despite the O’Keeffe’s remarks to interviewers that she’d taken only “about 20” snaps, or even just what you could count “on one hand,” Volpe identified among O’Keeffe’s own possessions more than four hundred photographs taken by the artist, as well as seven that found their way into the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art anonymously. Volpe divides the nearly 100 photographs in the exhibition into four sections: “History, Reframing, Light, and Seasons,” largely encountered in that order.

Just before the “History” section is an area with seats and a large continuing projection of an excerpt from Henwar Rodakiewicz’s 1948 documentary film Land of Enchantment: Southwest, USA made for the United States Information Agency which shows O’Keeffe both on the land and in her studio. From here on, the photographic images on exhibition are still.

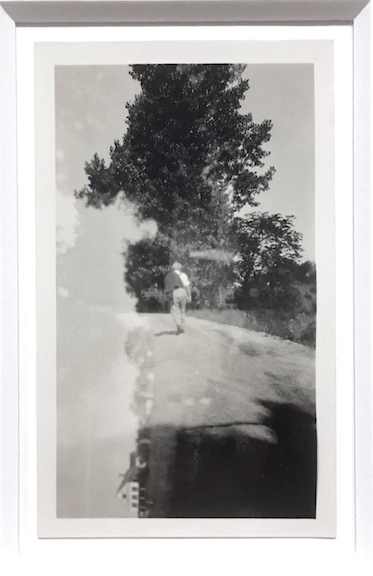

The earliest photographs in the exhibition are family pictures from childhood, likely made with the then revolutionary and democratizing Kodak box camera (the photographs were developed and printed by the manufacturer then returned to the owner with a newly reloaded camera). One fascinating photo in this History section is an accidental double exposure, made when O’Keeffe was 36 on an unknown camera, superimposing a photo of a man walking in sunlight (actually Stieglitz, at Lake George) with a turned on its side vertically, more distant rural landscape. The resulting image has both abstract and surrealistic attributes and is instructive in that O’Keeffe kept it (a screw-up most photographers then likely would have tossed, since both individual photographs were ruined).

(installation photograph by author)

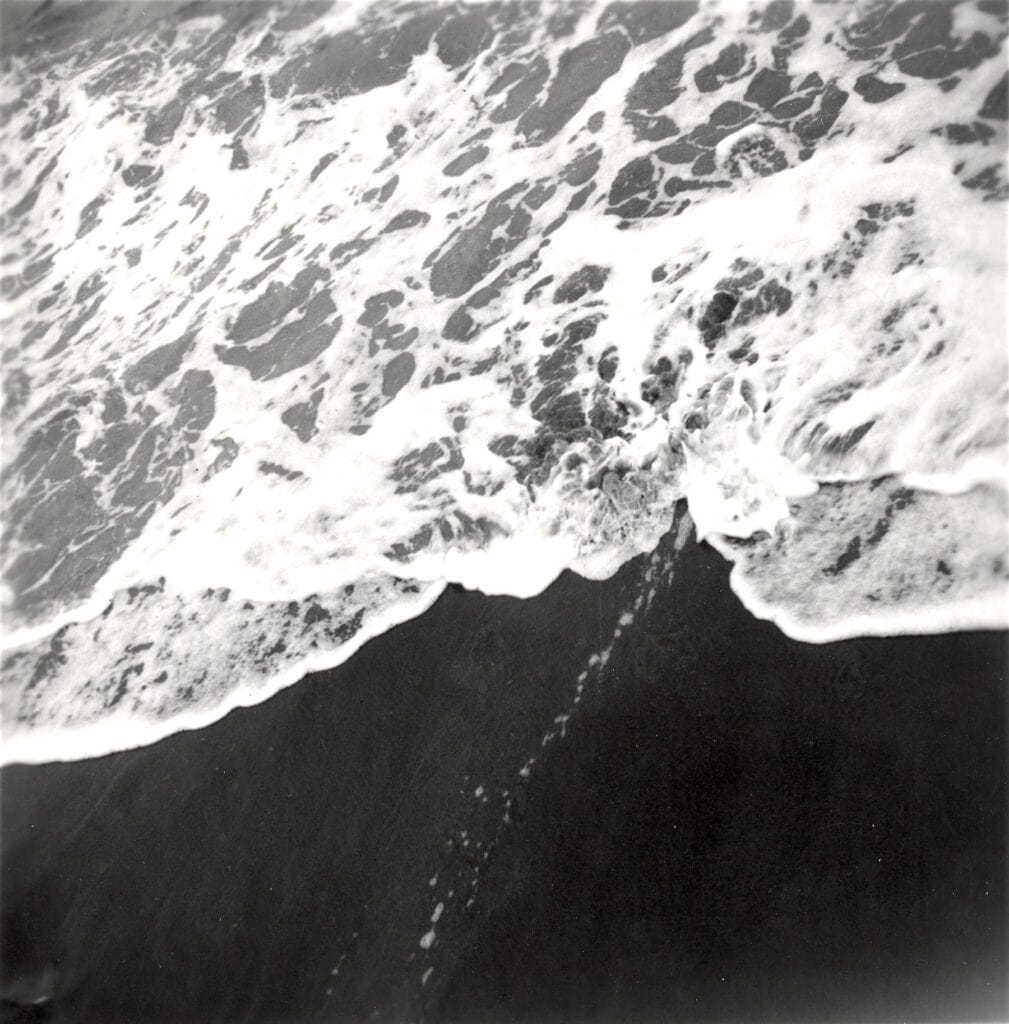

The first “body” of photos are a handful O’Keeffe made during a 1939 Dole-sponsored junket to Hawaii. I am not certain what camera she used, as the pictures are small and square, a format which feels somewhat constraining for her. A painting of the same period, Black Lava Bridge, displayed among them, is more comfortably expansive as a horizontal. Of particular interest is a beach scene taken from above with the suspended-in-time surf looking delicate white lace-like against the dark volcanic sand. In one of her letters home from Maui, she writes “The black sands of Hawaii have something of a photograph about them.” This seems mostly due to the observed reality itself being nearly black and white, and, in the one I cite, the single distant plane of focus virtually translating itself into a two dimensional picture.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Another interesting early-ish photograph (c. 1943-46) is a snap of an antelope looking back at the camera (“My back yard pet” she called it). There are light colored somethings (flowers?) behind the antelope which, due to the flattened perspective, seem to surround its head in a fairy-like aura. How the background moved forward in the photographic picture plane already interested O’Keeffe.

The three subsequent sections of the exhibition – Reframing, Light and Seasons – refer to the photographs themselves and how Volpe categorizes the way she sees O’Keeffe photographically, which relate to O’Keeffe’s painting as well and somewhat echo the trio of compositional concerns that she learned early on from her most important artistic mentor, painter and Columbia University art professor Arthur Dow: line, notan (light/dark), and color, which O’Keeffe distilled into the simple concept of “Fill space in a beautiful way.” More on this in a bit.

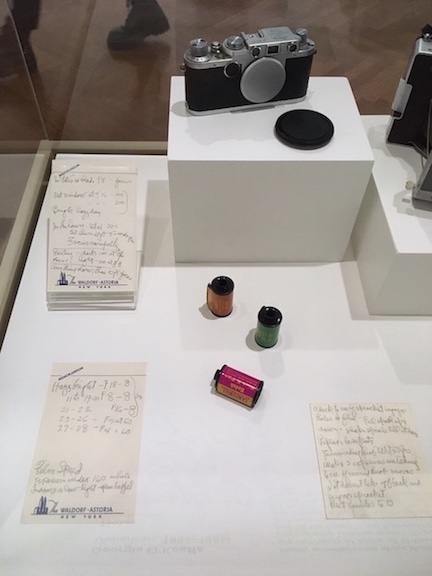

It wasn’t until the mid-’50s O’Keeffe began to photograph with greater intention (due to the tutelage of, and camera provided by, frequently visiting photographer Todd Webb, who’d even set the shutter speeds and aperture for her); and it wasn’t until the late 1950s that O’Keeffe owned her own camera (a Leica which Webb acquired at her request). Webb also developed O’Keeffe’s films and printed her photographs for her. O’Keeffe never did commit the camera’s technical requirements to memory. She relied on Webb and made herself a set of crib notes (on Waldorf-Astoria memo paper, on display in the exhibition; one begins: “Check to see if sprocket engages holes in film — pull spool up & down — shake spools till it does” while others tell her various settings to use and repeatedly remind her to “focus”).

(installation photo by author)

It may disappoint some photographers who come to the exhibition to learn that O’Keeffe had no interest whatsoever in the technical aspects of the medium or even the quality of the print. For her it was just about seeing. She wasn’t even impressed by the veracity of the medium. “Many people think photography is realistic. I think it lies,” she wrote. “I am often astonished to see something after I have seen a photograph of it. Often it isn’t accurate. It can be quite a bit different from the real thing.” This is something she doubtlessly discerned as well from the 330+ photographs Stieglitz made of her.

Despite several enlarged, wall-sized photographs in the exhibition of O’Keeffe using a Leica 35 mm camera (and the promotional image for the exhibition and book cover) it was a likely a third camera which she most enjoyed: an early Polaroid Land camera which O’Keeffe first encountered when longtime friend Frances O’Brien came to visit. O’Brien later recalled that O’Keeffe was fascinated with the instant camera, used it eagerly, and remarked she would get one. When Webb brought one to O’Keeffe in July 1964, he wrote in his journal that she was “like a kid with a fine new toy.”

As Volpe interprets the photographs O’Keeffe produced, they firstly are about reframing a subject (something quite familiar to photographers as inherent to photographic creativity), selecting where to put the edges of the picture, and how much of the subject matter to include in the framing. Volpe includes examples of numerous “reframings” as O’Keeffe searches for the strongest image. Volpe posits that no other photographer engaged in this practice of shifting a viewpoint and frame placement to find the strongest relationship of forms within the frame (a claim that’s difficult to believe), and that it is evidenced in her paintings uniquely as well – perhaps suggesting that it was photographing that taught her this “reframing” in her painting.

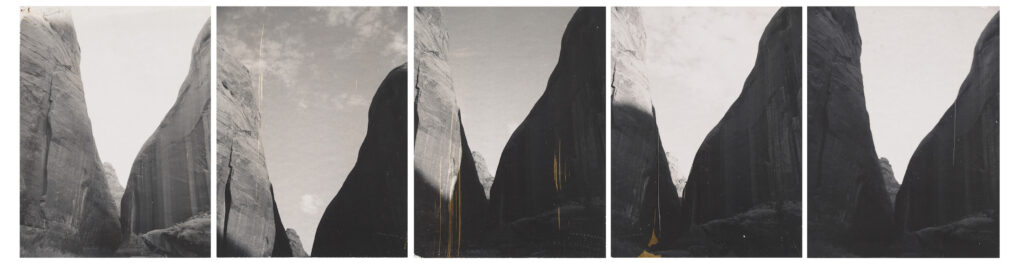

The section about “Light” is not so dissimilar from the former section, except for the presence of shadows, hence creating distinctions between where light lands on surfaces and the graphic quality of the shadows where it is blocked. The starkness with which this occurs in the New Mexican landscape is particularly emphasized in black and white photography but also often evident in O’Keeffe’s paintings. There is plenty of potential overlap between these two categories, light and shadow emphasizing the formal relationships within the frame. An example is the series of photographs O’Keeffe took in Glenn Canyon in September 1964 with the new Polaroid. After an initial “reframing” she returned to her initial framing of the scene, letting the growing shadows reshape the pictures.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

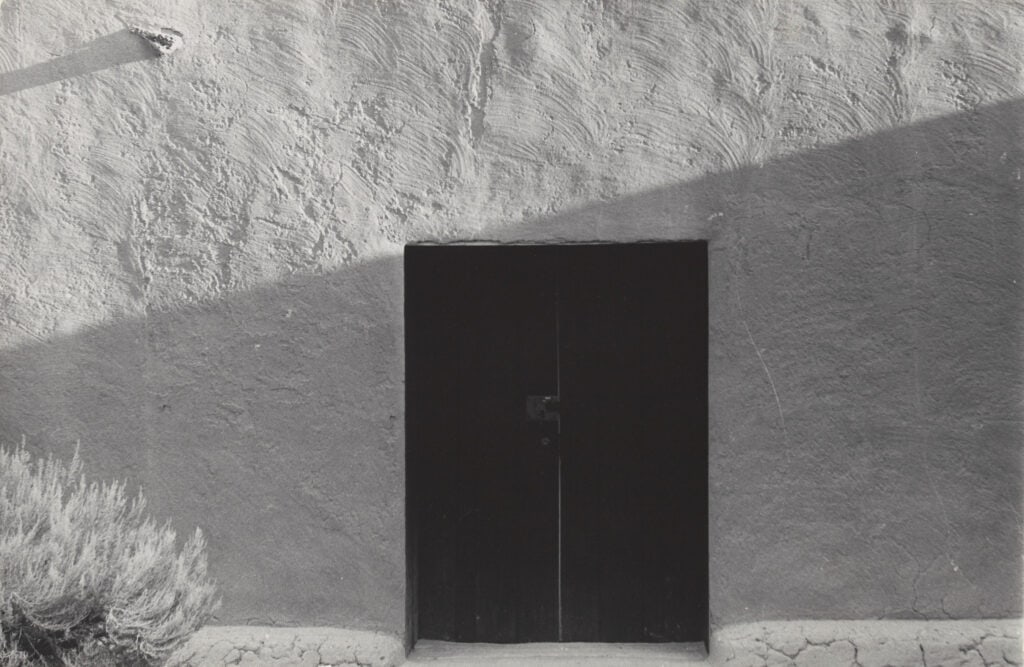

One subject which particularly attracted O’Keeffe was the inner courtyard (salita) of her home in Abiquiú, New Mexico, and its recessed, double door. It was the door – a stark, dark rectangle in the lighter adobe wall – which most affected her on the the run down house. “That door is what made me buy this house,” O’Keeffe wrote when she sent a photo of the door to the art critic Henry McBride. “I used to climb over the wall, just to look at that door. I’m always trying to paint that door — I never quite get it… It’s a curse — the way I feel I must continually go on with that door.”

O’Keeffe made at least 20 paintings and drawings of the salita door, starting in 1946, before she’d even fully moved to New Mexico. Photographing it, beginning in 1956, may have been an attempt to discover an other approach to painting it.

Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

In a nod to the Salita doorway, the CAM exhibition is designed so as to lead us to the sections through similarly simple, rectilinear openings in temporary walls, the first and last of these opening a view of a wall-sized image of O’Keeffe in the landscape, with her Leica.

(photograph by author)

There is an intriguing passage in O’Keeffe’s 1976 autobiography about looking out her bedroom window at a road which winds up toward a bluff, deciding to take a few photographs. “The road fascinates me with its ups and downs and finally its wide sweep as it speeds toward the wall of my hilltop to go past me. I had made two or three snaps of it with a camera. For one of them I turned the camera at a sharp angle to get all the road. It was accidental that I made the road seem to stand up in the air, but it amused me and I began drawing and painting it as a new shape.”

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Anonymous Gift, 1977.

© 2022 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

There are five photographs of that view in the CAM exhibition, surrounding a lone painting. From the shadows and growth of the shrubbery in four of the photographs, it is apparent that they were made together at the same time, despite differing dates accompanying each (1957 to 1959; it was explained to me that different loaning institutions independently determine their own dating for the objects in their collections). The fifth is the same scene snow-covered. Of the four, just one is a vertical and tilted. That’s the key photograph for me and quite likely the one O’Keeffe describes in her autobiography – and the road does appear to stand up on its own as the background supports it in the flattened photographic perspective (a perspective reminiscent of vertical Japanese scroll landscapes rather than the Western pictorial perspective of the Renaissance). This must have been an “aha” moment for O’Keeffe.

The painting selected to exhibit among the five photographs – Road Past the View, 1963 – contains the identical bluff in the photographs, but the road has transformed into a blue river snaking its way up a featureless white hill form. Look left, to the end of the line of photographs on this wall, at the photograph of the window scene in snow, to see from where the inspiration for the painting may have originated.

(installation photograph by author)

The snow covered scene photographed is intentionally not placed directly next to the painted landscape so as not to reinforce any expectation that O’Keeffe was simply transcribing photographs into paint (as the art critic Clement Greenberg suggested in his scathing review of her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, dismissing “the greatest part of her work” as “little more than tinted photography.” Whew!). But O’Keeffe did acknowledge the debt this particular painting owes to these photographs.

The “Seasons” section is a bit harder to define. Here is where these five photographs from O’Keeffe’s window are accompanied by the same view snow-covered (and the whiteness of the accompanying painting). Volpe attempts to make the case that, as with light and shadow, since “O’Keeffe photographed her environment in all seasons, [this] allow[ed] the change in nature to act as an inherent formal characteristic in her art work.” I think I’d have been more comfortable generally had Volpe chosen to organize/analyze the photographs employing Dove’s troika of line, notan (light/dark), and color (which could be about tone in monochromatic photographs).

Largely intentionally ignored though he may be in this exhibition, there is no way to exorcise the presence of Alfred Stieglitz entirely from an exhibition such as this. Most photographers are aware of the extraordinary extended photographic “portrait” Stieglitz made of O’Keeffe over years (including many highly intimate nudes – one local photographer who came to the exhibition its opening morning jokingly wondered where were the naked selfies). We might not even be seeing an exhibition like this were it not for Stieglitz, who encouraged and promoted O’Keeffe’s work from 1916 into the ‘40s, seeking to establish her as “the mother of American Modernism.” As James Voorhies, a painting curator at the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote in 2004, Stieglitz’s “relentless promotion of American art created new appreciation and new markets for this work, where none had previously existed. The current popularity of such artists as O’Keeffe… is in large measure due to Alfred Stieglitz.”

Yet when O’Keeffe wrote about photography’s impact on her and off-handedly remarked “Perhaps the clarity of the [photographic] print influenced me,” she likely was talking more about Paul Strand than Stieglitz, who was somewhat late in emerging from the fuzzy realm of Pictorialism into the sharp focus of Modernism in photography. It was Strand who showed her a photograph he’d made which rejected the illusion of realistic perspective. “I have always thought,” she wrote, “that Strand was the first to consciously use in photography the abstract idea that came to us through cubism.” This despite the claim that it was Stieglitz’s 1907 proto-documentary, proto-cubist photograph The Steerage which was supposedly hailed by Picasso as “doing in photography what I am trying to do in painting.” (Picasso also made photographs, and was particularly fond of photographing his own paintings to examine, in neutral grey tones, their inherent formal and compositional relationships.) 1907 was also when Picasso painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (which he titled Le Bordel d’Avignon), his nascent Cubist work.

Strand’s work seems to have affected O’Keeffe in a more familiar way too, as she writes to him soon after meeting him in New York in 1917, from the train back to Texas, “I believe I’ve even been looking at things and seeing them as I thought you might photograph them — Isn’t that funny — making Strand photographs for myself in my head.” Her own photographs (and paintings) bear little aesthetic relationship to Stieglitz’s photographs.

Stieglitz didn’t publish The Steerage until 1911, the same year he exhibited Picasso’s work at 291 and in Camerawork, and the same year he travelled to Paris and had those conversations with Picasso. Picasso didn’t exhibit Les Demoiselles until 1916, the year a 52 year-old Stieglitz met a 28 year-old school teacher from Texas named Georgia O’Keeffe and included her artwork in an exhibition at 291 (mounting a solo exhibition for her in 1917, the gallery’s final year). World War I was just ending and the Spanish Flu pandemic was just a year away, which O’Keeffe would contract in Texas, causing her to move to New York permanently, so that Stieglitz could care for her in recovery. That year she became his lover, photographic subject and muse (and eventually wife), a passion that fueled the creativity of both. In 1927, O’Keeffe went to New Mexico and fell in love again, this time with a place, which became the focus of her art from then on. Steiglitz continued to aggressively promote her work. Stieglitz died in 1946 and three years later O’Keeffe moved to New Mexico permanently.

I mention all this to remind what an extraordinary period was occurring in art, photography, and society at the time of O’Keeffe’s artistic emergence. Art and photography were deeply linked both causatively and antagonistically (as art broke its last bonds to representation, while also enabling photography’s Modernist exploration of itself).

O’Keeffe indeed came to be recognized as “the Mother of American Modernism” and much more. In 2014 the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum auctioned off her painting Jimson Weed for US$44.4 million, the highest-priced artwork by a female artist in history to that time. In another record, when it opened in 1997 the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum was the first art museum in the US dedicated to a female artist.

A museum curator can’t focus solely on their personal predilections in creating content for their institution; they must focus also on the needs of the institution and the tastes of community. The mystique of the O’Keeffe name will doubtless generate considerable interest and attendance. CAM Photography Curator Nathaniel Stein confessed “probably 90% of the people who’ll see this exhibition come to see those 11 paintings.” Such is the allure of Georgia O’Keeffe the painter, the artist, the woman. Almost immediately TV ads were promoting the exhibition.

It’s fair to say, I think, that, of the remaining 10%, those hoping to see a block-buster photography exhibition will be disappointed. The photographs generally are quite small and rather homey (a favorite photographic subject is her black chow Bo-Bo), a far cry from what tends to be expected of contemporary photography exhibitions (an exception being the large Karsh portrait of O’Keeffe). While O’Keeffe admired Strand’s photographs and was trusted to install and perhaps even select Stieglitz’s and others’ photographs for exhibition, she herself cared little about the medium, and certainly would not have considered herself a photographer. The 400+ O’Keeffe photographs Volpe identified in her years of searching represent an average of fewer than seven photographs taken a year – what many people now take with their phones in under a minute.

I also find myself thinking O’Keeffe would have been appalled to learn her “snaps” sent to friends and recorded notations made for herself, including streakily fixed Polaroids, would someday be matted, framed and exhibited as a museum exhibition and travel the country, representing her as a photographer, knowing how incredibly particular, protective and controlling she was about her actual art (she had no problem destroying paintings she deemed unworthy and let major sales fall through if she was unable to control the work’s display and care.)

But, hey, it’s Georgia O’Keeffe. If you install it, they will come. And I have to give kudos to the Cincinnati Art Museum’s photography curator Dr. Nathaniel Stein and the exhibition designers Emily Hartig and Lauren Walker for their effective presentation of the exhibition. My only quibble is adding the museum’s Karsh print, as it rather outperforms the other work in physical size and print tonalities (to be fair, Karsh photographs usually outperform most photographic work they are placed near); it might have been better nearby, referencing the exhibition.

(Collection of Cincinnati Art Museum)

Having said all this, for those willing to engage the exhibition within its own parameters and invest an exploratory interest, it can be quite rewarding, particularly for O’Keeffe’s devotees. As Stein says rather modestly “This is a chance to re-meet someone you think you already know and learn something new about her.” It’s actually more than that: it’s an opportunity to think about the medium of photography at a significant time in its development and its formative roles in O’Keeffe’s formidable artistic development… which is quite enough.

1959, printed later, inkjet print, Todd Webb

Archive. © Todd Webb Archive, Portland, Maine, USA

(installation photo by author)

Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer is installed in the Thomas R. Schiff Gallery (Gallery 234) on the second floor of the Cincinnati Art Museum through May 7, 2023. It is free to CAM members; for all others there is a $12 charge ($8 for students, seniors and children). On the ground floor, near the main lobby, in the Craig & Anne Maier New Acquisitions Gallery, Stein has installed an additional mini exhibition of recent additions to the photography collection by Dawoud Bey, Larry Fink, Henry Horenstein, Christine Osinski and three Kamoinge Workshop photographers, including Adger Cowans, Louis Draper and Ming Smith, the lone woman member of the Kamoinge group.