As it turns out, Chicago-native Joan Mitchell’s home and garden in Vétheuil, FR was just a 9-mile hike from Claude Monet’s Giverny paradise, where he painted nearly 250 water lily paintings during his last three decades.

Huile sur toile, 200 × 180 cm

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

At first blush, their proximity could be said to justify this juxtaposition of pioneers from such divergent movements as Impressionism and Abstract Expressionism. What captured my imagination, however, was the fact that both were garden afficionados who painted landscapes made from their own hands, rather than places created by others. Of course, painters have rarely painted scenes as is, but few landscape painters have been so engaged in the origination of their subjects, as this exhibition suggests Monet (1840-1926) and Mitchell (1925-1992) were (with or without a lot of help from additional gardeners, etc.).

Proof of this novel pairing is the fact that “Claude Monet- Joan Mitchell, Dialogue” is the first exhibition to demonstrate a connection, though museums have long recognized Monet’s influence on postwar American painting. Fondation Louis Vuitton Artistic Director Suzanne Pagé has situated 40 of his late paintings (1914-1926) in dialogue with her 25 paintings and ten pastels. Scores more are exhibited in the foundation’s lower galleries in the concurrent “Joan Mitchell, Retrospective,” co-curated by Sarah Roberts and Katy Siegel for SFMoMA and the Baltimore Museum of Art. Unless you’ve visited Musée Marmottan Monet, which lent 25 of the 40 Monets, it’s unlikely that you’ve experienced so many Monets at once, as are available here.

What makes this pairing authentic, rather than merely speculative, is that Pagé curated Joan Mitchell’s first exhibition in a French museum in 1982. She vividly recalls Mitchell’s defiance regarding Monet’s influence on her practice, yet she also remembers standing with Mitchell on her terrace overlooking Monet’s former home (prior to Giverny). Franco-American composer Betsy Jolas actually found La Tour on Rue Claude Monet in Vétheuil. Little did they know back then that Monet actually lived across the street between 1878 and 1881. Although Mitchell admitted her admiration for Monet’s late paintings, she felt a far greater affinity for Van Gogh’s paintings, whose brighter palette resonates with her use of intense colors. Perhaps she found Monet’s pastel palette too delicate (coded “feminine”). A researcher at heart, Monet primarily painted sunlight’s temporality. How sunlight enhances water’s reflective properties, engenders bouncing shadows, and transcends depth are natural properties necessitating whitened hues.

Already 42-years old by the time Mitchell moved from Paris to Vétheuil, she was a mature artist whose fascination with nature scenes preceded her arrival. One year earlier, she painted My Landscape I and II (both 1967), paintings drawn from memories she claimed to carry around with her. In her 1982 exhibition catalogue, she asserted, “In all my paintings there are trees, water, grasses, flowers, sunflowers etc. …but not directly.” No doubt, living at La Tour stoked her passion for gardening, plant life, and the vast Normandy countryside, which, along with her love of music and poetry inspired her brushstrokes to spread across the canvas. Although this exhibition teases out many more ties to Monet than Mitchell herself admitted, such associations strengthen our understanding of Monet, rather than diminish her greatness as an artist. Presented here “de-framed,” Monet’s large-scale immersive paintings of flowers, ponds, and trees have never felt more contemporary. While Monet aimed to capture nature’s “sensations,” Mitchell focused on “feelings” by creating paintings that provoke feelings associated with nature. Each fall, she painted a linden tree, while Monet repeatedly painted a weeping willow.

On several occasions, Mitchell created “garden pictures” as tributes to loved ones, such as her sister Sally (1982), friend Audrey Hess (1975), curator Thomas Hess (1979), psychoanalyst Edrita Fried (1981), and even her dog. As such, these “garden pictures” double as bereavement strategies, enabling her to cope with her own feelings of grief and loss. It’s no wonder Mitchell believed, “Painting is the opposite of death. It permits one to survive; it also permits one to live.”

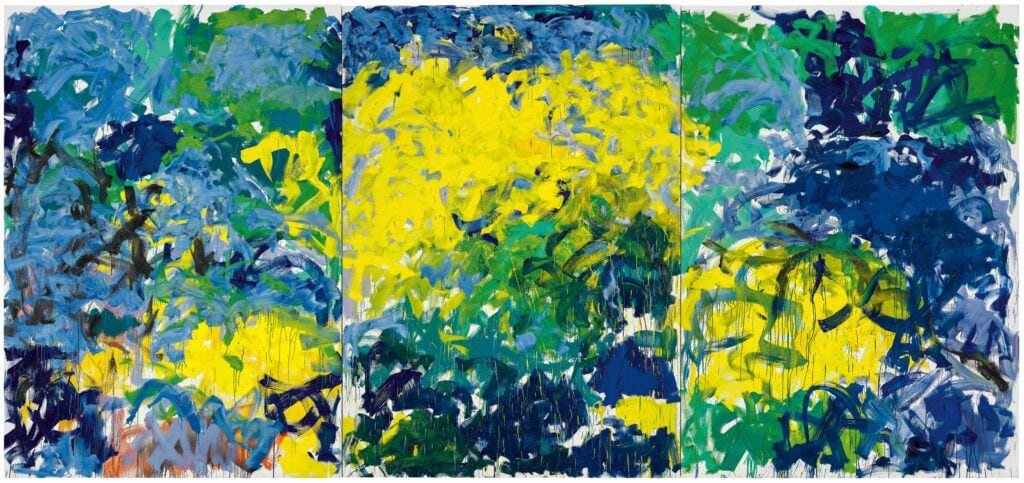

By contrast, the astonishingly monumental four-paneled Quatuor II for Betsy Jolas (1976)

Oil on canvas, 279,4 × 680,7 cm

Paris, Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, en dépôt au musée de Peinture et de Sculpture, Grenoble

Courtesy of Joan Mitchell Foundation © The Estate of Joan Mitchell

celebrates the still-alive Franco-American composer, while the diptych Two Pianos (1980)

Oil on canvas, 279,4 × 360,7 cm

Private collection

© The Estate of Joan Mitchell

Photo : © Patrice Schmidt

captures pianists duetting the score of the same name by still-alive French composer Gisèle Barreau. Although I’ve never actually heard this piece, I can imagine its powerful resonance in my mind’s ear, thanks to Mitchell’s broad orange brushstrokes vibrating against French blue and lilac brushstrokes. Her opting to immortalize female composers counts as a feminist strategy.

La Grande Vallée, Mitchell’s cycle of 21 paintings, which includes five diptychs and a triptych, is

Oil on canvas, 280 × 600 cm

Musée national d’art moderne, Centre Pompidou, Paris

shown here for the first time since 1984. What’s amazing about this series is both their total flatness, and her almost ribbon-like brushstrokes that offer a counterpoint to pointillism. In fact, they don’t resonate as landscapes unless one consciously attempts to experience them as landscapes. Despite Frank Stella’s 1966 mantra “what you see is what you see,” Mitchell realized all along that no artwork is devoid of content, however abstract or minimal its appearance.

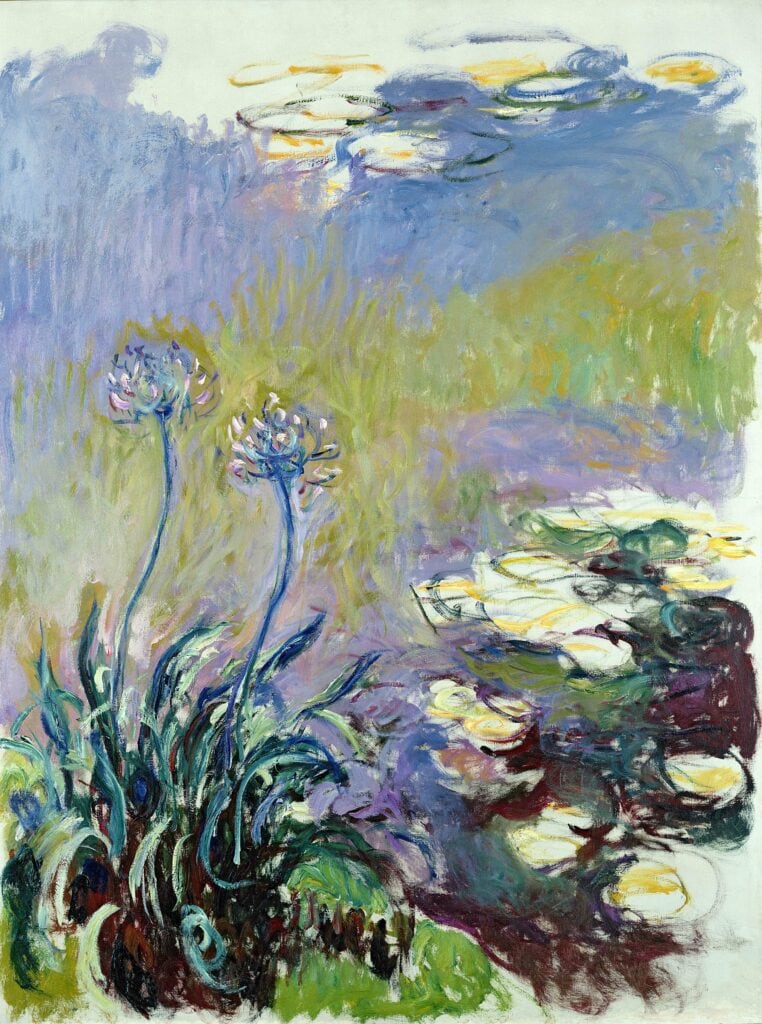

Oil on canvas 200 x 150 cm

Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

Without a doubt, one of this exhibition’s highlights is the reunion of three panels of Monet’s triptych Water Lilies (Agapanthus)(1915-1926), each purchased by a different US museum and not seen together since 1956. Even if Mitchell’s terrace granted her access to the very vistas that once captivated Monet, what they truly shared was not proximity, but the audacity to celebrate subjects in which they had a hand, whether trees, flowers, friendships, or sounds.

“Claude Monet- Joan Mitchell, Dialogue” is on view October 5, 2022- February 27, 2023 at the Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris, FR.