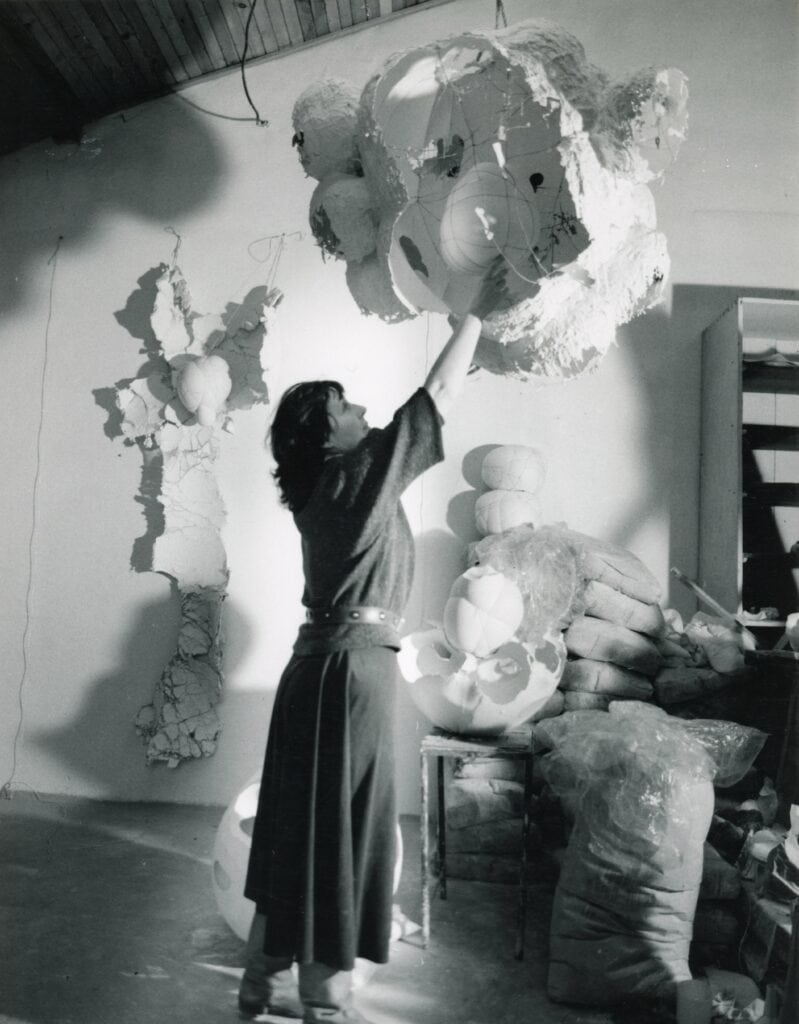

Living in Košice (eastern Slovakia), Maria Bartuszová (1936-1996) was effectively cut-off from the western artworld. Even so, she was both incredibly experimental and prolific, producing over 500 sculptures during her short life. As the above image indicates, Bartuszová‘s oeuvre, inspired by water droplets, melting snow, grain seeds, germinating planta, and cell division, is diverse in scope. What makes her oeuvre particularly interesting is her wide-ranging art-making process. Tate Modern’s exhibition included public art maquettes, kindergarten park prototypes, photographs, participatory art, and site-relational installations; all exemplary of process art, whereby raw materials that did their thing. Put another way, the how of making gets incorporated into the what that is made, Had she lived in NYC or central Europe, she would have exhibited alongside other post-minimalists. Like most post-minimalists, she briefly flirted with minimalism, or in her case, the tendencies of the local Concretist Club.

Given the high status for artists and the preference for anti-bourgeois gestures during the Communist era, her radical art was in high demand. Her public artworks activated modernist buildings, her fountains charged plazas with refreshing energy and her playground equipment challenged children. As a bystander, standing amidst her various projects at Tate Modern, it looks like a full life, replete with difficult puzzles to solve. She described the process of her malleable plaster objects such as Folded Form (1965) thusly, “Touch, pressure (discharge, oppression, pull, super-pressure, over-pressure), counter-pressure, resistance, tension of form, cracking, repletion, deflation, suppleness, softness, release, hardness….”

Clearly inspired by and impressed with nature, Bartuszová incorporated natural elements into her sculptures and photographed her artworks outdoors, either dangling from a plum tree or resting alongside a river. In light of nature’s tendency to change, she didn’t cover up her objects’ imperfections. She wrote, “I am thinking of all the trees in the world, flying birds, their nests with eggs, abandoned nests. And in that moment, I, too, become a tree, a bird, an egg in a nest, an abandoned nest.” With Melting Snow l (1985), one sees how several branches embedded beneath and floating atop a plaster skin structure creates a terrain across its surface, while accentuating its fragility. She had taken a photo of Auguste Rodin’s 1900 plaster study for Two Eves and Crouching Woman, a larger than life wall work similarly ensconced with a branch. Given his tableau’s verticality, people standing in front of Melting Snow I fill in for Rodin’s figures.

This last sculpture captures how she collaborated with gravity, what she called “gravistimulating shaping,” and hard materials such as wood or rocks to compress the plaster, engendering stackable and interlocking plaster blobs. Sometimes, she wrapped the plaster around a rock or placed heavy rocks or wooden blocks atop, while at other times, she worked under water to conserve round forms, otherwise squared by a table.