Through April 30th, 2023, MOCA presents “Henry Taylor: B Side.” It is the most extensive view of Henry Taylor’s multi-layered oeuvre yet. Taylor, a Los Angeles fixture, navigates blackness and personhood by turning a balanced eye to the relationship between collective and individual existence. His exhibition gathers assemblages of people from his everyday life together with depictions of historical and popular figures like Eldridge Cleaver, the Obamas, Jackie Robinson and Tyler, the Creator. Taylor’s range might be the most impressive element of the exhibition. Upon initial entry, the works are deceiving. I found myself gazing at the brushstrokes and the lines, which he crafts with purposeful imperfection. The work holds an everyday quality that should inspire young artists in their own work. Stylistically the collection ranges from complex, wall-encompassing portraits, to a room wide display of a Black Panther assembly, to the small everyday objects that he painted on in his early career. One of my favorite pieces – a cigarette box with two chicken wings painted on it – is displayed with equal stature to larger, more ambitious pieces. Taylor’s form and content work in tandem. By collecting this range of figures, Taylor collapses the mythical and the everyday into each other. Robinson and Obama are everyday people alongside the friends and family members that his portraits celebrate. His style displays art practices that showcase both years of technical skill and a breadth output that should inspire any aesthetic practitioner.

Acrylic on canvas, 71 ¼ x 83 3/4in. (181 x 212.7 cm).

Cypres Collection, Los Angeles.

Image and work ©Henry Taylor, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Photo by Joshua White.

The Jackie Robinson painting is a deft example of the artist’s experimentalism. This view should be familiar, depicting a famous image of Robinson sliding into home plate. His hat floats off backwards. Taylor imbues the image with the kind of grit that Robinson played with. Some techniques here recall the street culture of Basquiat’s style like the words at the top that read “A Jack Move,” and areas of the canvas that are left void of brown paint. The painting doesn’t have a unified background, as patches are left unpainted and unrefined. Robinson’s face is also left without much detail, perhaps to grant him an everyman aura. Viewers can see themselves in such an important icon of baseball and black history. Taylor uses formal technique to bring the legend of Jackie Robinson down to Earth, reminding us of the humanity of his character that continues to endure and appeal to us today.

Acrylic on canvas, 156 x 74 in. (396.2 x 188 cm)

Collection of Marcia Dunn and Jonathan Sobel.

Image and work ©Henry Taylor, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Photo by Cooper Dodds.

Baseball, of course, is an enduring element of the popular America imaginary, just as the 4th of July is. Taylor’s painting, The 4th, also depicts the American holiday with a deconstructive lens. Notably, if it weren’t for the title, one might not know that the painting captures a 4th of July moment. The painting features a person whipping up a variety of meat dishes on a charcoal grill. The grill, which is filled from rim to rim, looks to be cooking food for a decent sized gathering. The person is solitary though. Their face, like Jackie Robinson’s, is similarly obscure. The moment is meditative. A grill master performs their duty for the neighborhood. The frame is devoid of anything “American” – no flags in sight. This snapshot is stripped of typical nationalist symbolism, suggesting an aesthetic rejection of the state. The focal point of this gathering is not fireworks and flags, but the ever-binding power of food. The canvas, which is one of the largest among the gallery walls, blows up this celebration of food to larger-than-life proportions.

Acrylic on canvas, 62 5/8 x 49 7/8 x 3 1/8 in. (159 x 126.7 x 8 cm).

Image and work ©Henry Taylor, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

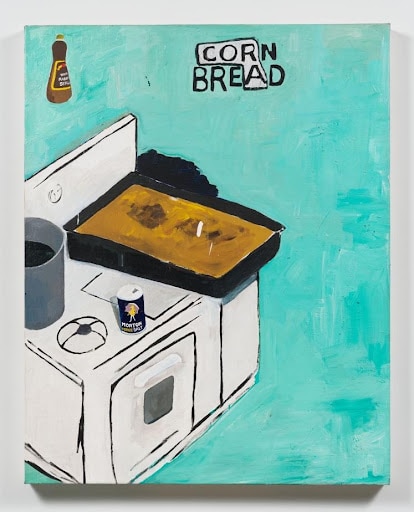

Indeed, food is a consistent theme for Taylor. Recall the chicken wing cigarette box. Another canvas shows a pan filled with corn bread. The words are near the top, while the left of the canvas is occupied by a stove with corn bread on top. It is a curious image. The right half is empty, just filled with a light blue background. The cornbread is the closest thing to a focal point, but it is still decentered. This painting utilizes a different tactic, perhaps the opposite of demystifying Jackie, more like the culinary elevation of The 4th. The cornbread, with a bottle of syrup floating above it, almost appears to be a sort of mythical presence in this kitchen. Despite the decentering, the lack of surroundings allows the focus to lie solely with the edible subjects of the painting, surrounded by this light blue glow. For Taylor, food is a central element of cultural significance. It is a community binding force, and a mysterious, life sustaining form of sustenance. It is also a vessel for critiquing white American nationalism.

At MOCA Grand Avenue.

Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA).

Photo by Jeff McClane

Taylor’s range is crucial to the exhibition. Some paintings highlight everyday food objects while some make direct political statements. One painting hauntingly depicts the visceral shooting of Philando Castile in his own passenger seat. We could characterize it as a protest painting, which is situated in historical context with the next room over – formally a far-cry from his paintings. That room brings us into a time capsule by staging a Black Panther rally. Mannequins are clothed in leather jackets, which sculpts a life-sized imagination of those rallies. They are adorned with buttons and berets. In front sits a podium with a microphone built to project the voice of one of the famed leaders of the party. The mannequins don’t have heads, recalling the facial obscurity of the paintings of Robinson and the grill master, inviting viewers to project themselves into this collective political vision.

The space is on another end of Taylor’s range, which stretches from food to politics to myth. Reading across this range allows us to see Taylor stripping food of mundanity and revealing the political, as well as his reflection on the haunting mundanity of instances like the viscerally racist murder of Castile that continue to unfold across America and beyond. Reading the Castile painting next to the Black Panther room grants deeper historical context for the ongoing challenges of black political struggles. The culmination of the exhibition depicts Taylor’s view of reality. The everyday is intertwined with complex and deep histories. These histories are to be remembered, but the collectives such as family and friends are to be highlighted and celebrated.