Concurrent with the Cincinnati Art Museum’s presentation of “Picasso Landscapes: Out of Bounds” (on view through October 15), the Brooklyn Museum of Art has organized “It’s Pablo-Matic: Picasso According to Hannah Gadsby,” co-curated by Australian comedian Hannah Gadsby whose stand-up special Nanette (2018) disses Picasso’s misogyny. Gadfly Gadsby’s wry commentary (both legible and audible) supplements the BMA exhibition of eight Picasso paintings and numerous etchings juxtaposed with scores of artworks by women artists culled from the BMA’s collection. I mention this controversial exhibition because it forefronts a philosophical dilemma that “Picasso Landscapes” largely escapes. Should what we know about the artist alter our view of their art? Can an indecent person also be a decent artist, or not really? Personally, I don’t entertain such worries, since being a great artist requires great generosity. If the art is generous, so be it.

Describing Picasso’s sway today in the New York Times, biographer Deborah Solomon noted, “The painter’s influence lingers everywhere, from the fractured forms of contemporary portraiture to the digital collages of TikTok.” These days, dozens of young painters, such as Dana Schutz or the French artist Anastasia Bay, are renowned for paintings whose dysmorphic forms evoke Picasso’s inscrutable style. The dynamically-installed “Picasso Landscapes” features 34 rather modest landscape paintings, two small sculptures, a print, and several drawings, though not all are landscapes, which is unfortunate.

I say “unfortunate” because his figurative paintings prompt us to reflect upon Picasso the person in ways that his delightful landscapes do not. Towards this show’s end, one is confronted with five figurative paintings and a print, namely Le Peintre (1934), The Aubade (1965), The Three Bathers (1932), Guitar Player and People in a Landscape (1960), Le peintre et son modèle dans un paysage (1963) and Bachanal with Black Bull (1959). Even if their distorted imagery and perverse content are largely personal confessionals, some offer cathartic experiences, as if the artist has depicted our darkest thoughts. Here, Picasso noticeably depicts painters as voyeuristic scoundrels. Aubade, or “dawn serenade,” features a horny horn player whose audible audaciousness has seduced his listener to sleep. Picasso’s breasty bathers are too cartoonish to offend, while a bacchanal with a bull is just plain silly. Although these outdoor scenes fit this exhibition’s theme, they are veritable mood changers. No doubt, these six artworks demonstrate that Picasso was a “bad boy” artist avant la lettre.

With his landscape paintings, however, we primarily reflect upon Picasso’s relationship to a particular place, his attention to details available each vista, his appreciation for trees, and most importantly, his diversity of experimental painting techniques. This exhibition, which is effectively a travelogue of Picasso’s summer painting excursions, begins with Mountains of Málaga (1896), a photorealist painting of a mountainous desert painted when he was around 15. As if to break the third wall, he left a sliver of its left and top edges unpainted, so you know a painter made it. Given this tiny painting’s uncanny credibility, one soon realizes why he was labeled a genius from the getgo. Interior (1900) features a city view from the vantage of an apartment window, a perspective he returned to in View of Cannes at Dusk (1960). While in Paris, Picasso tried out Impressionist cityscapes à la Camille Pissarro and flattened figures à la Émile Bertrand. Following Paul Cézanne’s posthumous retrospective in 1907, he embarked upon Cubism. In 1909, he spent several months in Horta de Ebro, where a decade earlier he went to recuperate from depression. This time, he dedicated himself to perfecting his newly invented Cubist style by painting voluminous mountains, cities, and trees as assemblies of geometric shapes.

Since landscape paintings tend to be more fantasy than reality, it hardly matters that Picasso’s style post 1900 veers far from verisimilitude. By 1920, paintings painted in Juan-les-Pins appear totally flattened out. Resembling sticky Colorforms, his paintings from this era no longer hint at dimensionality.

Three paintings here from 1932 capture the Normandy town Boisgeloup under torrential rain. Picasso’s heirs still own the 18th century Château de Boisgeloup, where his first wife Olga lived until her death in 1955, and occasionally open it up to the public.

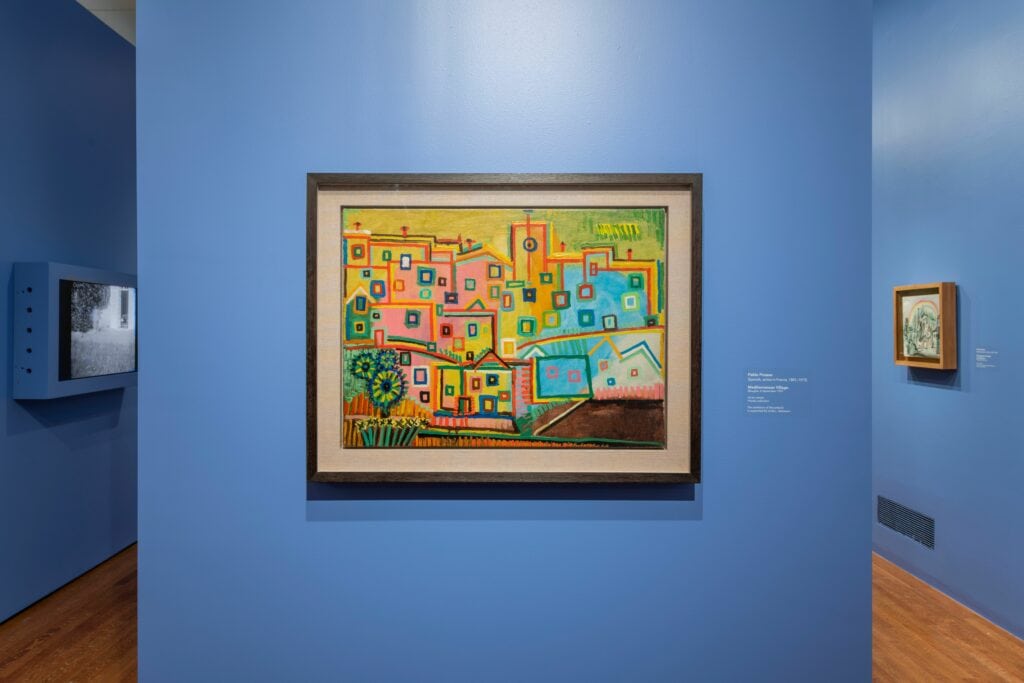

He spent the first year of World War II in Royan, a town known then for its grand café. Bombed during the war, Café à Royan lives on in Picasso’s 1940 painting, as well as dozens of post cards from that era. Even Picasso’s studio in Royan was leveled, but luckily his paintings were stored in a bank vault during the war. By far, this show’s most ‘uncharacteristic Picasso’ is Mediterranean Houses (1937). Extremely flat, it’s comprised primarily of colorful squares and green circles, and it offers either a bird’s-eye city plan or a street-level view of houses with windows. Was Picasso the first to envision circuit boards?

After living for seven years in Vallauris, Picasso moved in 1955 to the Villa La Californie in Cannes. By 1958, Cannes was becoming a construction zone, so he transferred his entire collection to his newly-purchased Château de Vauvenargues, just outside of Aix-en-Provence. Cézanne who once lived in nearby Aix-en-Provence had painted numerous Mont Sainte-Victoire canvases, whereas Picasso focused on the village nestled at its foot instead of the mountain.

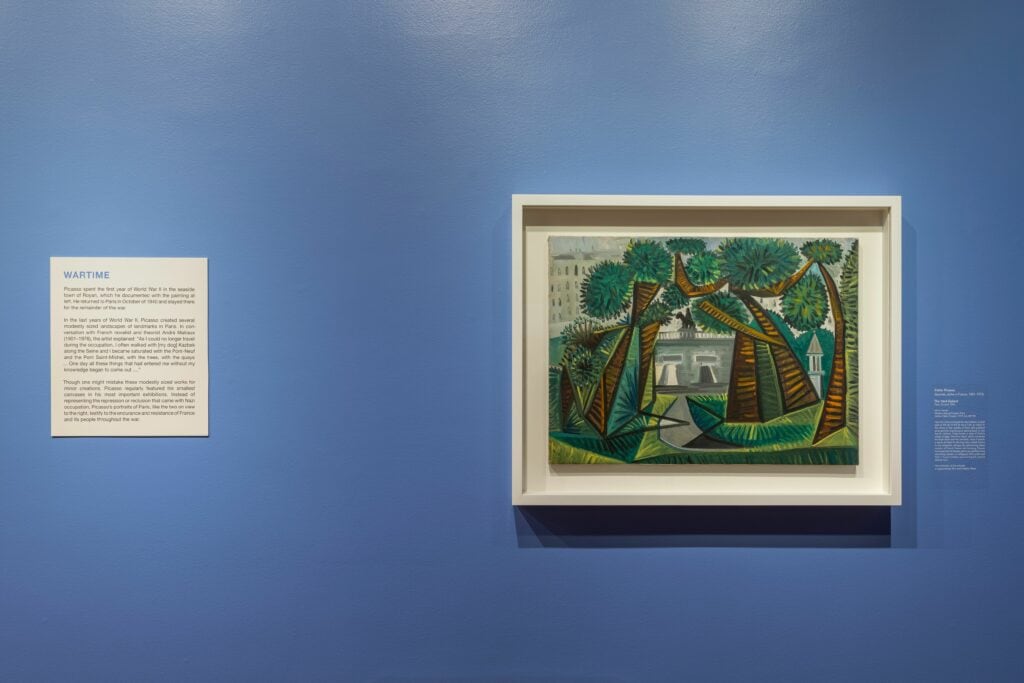

Finally, he settled in Mougins in 1962, where he lived for the last eleven years of his life. There he painted numerous fantasy landscapes, whose style resembles Le Vert Galant (1943), depicted below.

The numerous paintings of trees on view here give one a sense of how varied his style was over the years. Each couldn’t be more different than the other. Still working in a realist style, he painted Grove (1897-1898), a portrait of five tree trunks whose leafy branches are barely visible, which resembles Maurice Denis’ Landscape with Green Trees (1893). Not only does he exclude the trees’ leafy branches, but he left a rather large sliver of an unpainted surface. Surely, both gestures are “anti-photography” jibes, as if to stress the dominance of the artist’s hand over the everyman’s eye.

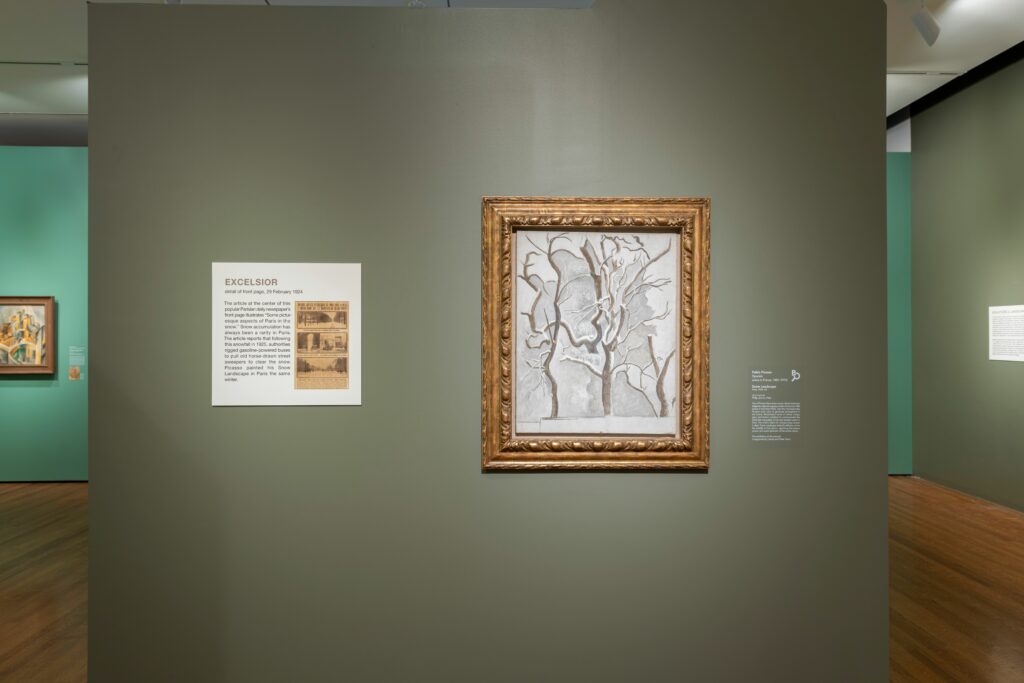

With La Rue-des-Bois (Landscape) (1908), one of his earliest Cubist paintings (depicted above), the tree is no longer legible. One must interpret its shapes, rather than read them. What’s wonderful is that the scale is a total mystery. Is this the forest floor or the canopy? With Snow Landscape (1924-1925), he captured the loneliness of ghostly, leafless trees draped in snow using no more than fat and thin black lines.

Hearkening back to Grove, some fifty years earlier, Le Vert Galant (1943) captures a family of five (or is it six?) leafy trees. If one looks closely, one senses that he crafted these bushy trees from brown trapezoids and green triangles of varying sizes. I say crafted because it looks like a painting of a collage made from bits of corrugated cardboard and colored paper scraps.

Finally, we find palm trees sprouting in a couple of paintings here, the first one appearing in Landscape (1957), painted at Villa Californie in Cannes, one of the first French cities to adopt this non-native species as its own, and the last one graces Landscape (1972), painted in Mougins the year before Picasso passed. Palm trees prove especially appealing since they exude exotica, yet conveying palmtreeness is relatively effortless.