In 1582, poet Moderata Fonte described women’s talents as “hidden gold”—buried deep in the ground, waiting to be unearthed, polished, and celebrated. This metaphor frames the “Strong Women of the Italian Renaissance” exhibit at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA), showcasing that gold through masterful artworks and intricate artifacts. While the “strong women” angle requires a curatorial jackhammer at times, this rich, atmospheric exhibit is certainly worth a visit before it closes on January 7.

The show shines brightest when it coaxes the viewer to a more generous view of women of the renaissance period—or to see them at all, as their work both in the public sphere and in the home often left them anonymous. This exhibit does feature woman artists of the period, but it moreso aims to shift our viewpoint of women’s actions as “strength” that shaped their society and the artistic artifacts that reflect that role.

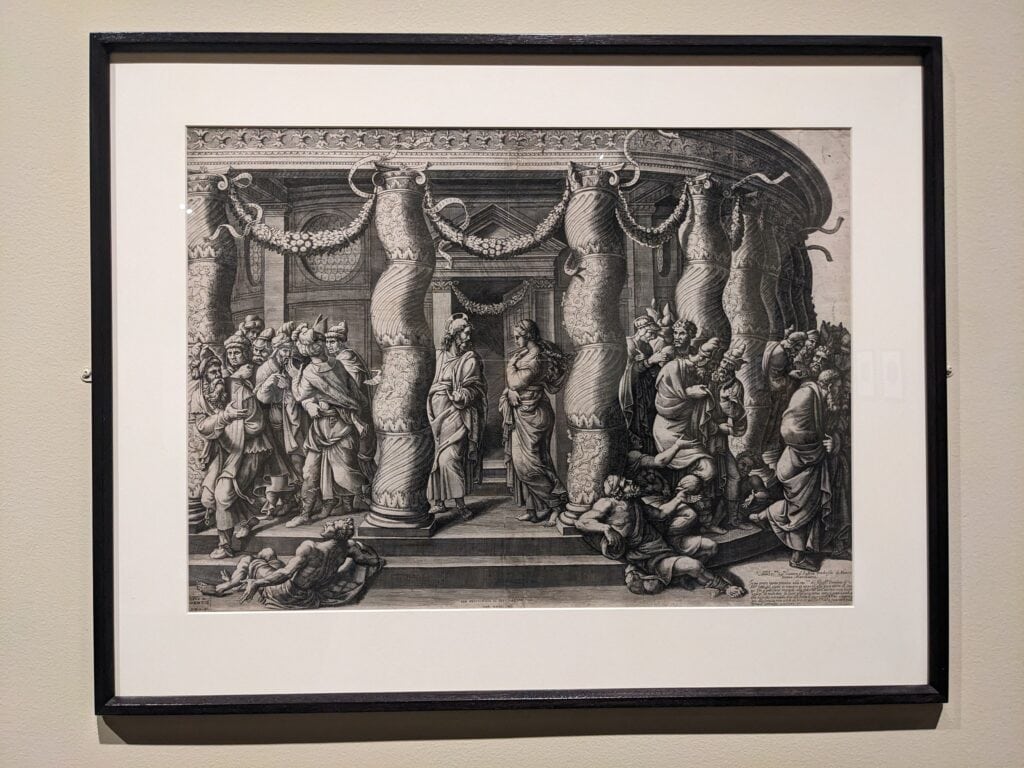

Woman artists of the time typically had access to training through their father’s artistic practice or connections. Diana Mantuata, for example, was a prolific printmaker studying under her father, an engraver and sculptor. She eventually received papal privilege, meaning that only she could market and profit from her work for ten years—extremely rare for a printmaker, and even rarer for a woman artist. She courted patrons by dedicating work to them, and actively positioned herself as a pope-approved, high-achieving artist. Similarly, painter Sofonisba Anguissola created more self-portraits than any other artist of the period and served at the court of King Phillip II of Spain.

Many of the artists included are men, but only pieces that portray womanhood in a powerful, wise, or courageous way. It feels a bit subjective to put these under a “strong women” banner, an excuse to include some of these masterful renaissance works, but I’m not complaining—if nothing else, they add atmosphere and context. For example, Bernardino Luini’s stunning “Salome with the Head of John the Baptist” (1515-25)—a famous subject, but apparently this lovely piece shows her more pensive than most, her turned-away face suggesting a remorse not usually attributed to her cold-blooded actions. A bronze bust of Cleopatra by Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi also falls into this category—it shows, the MFA notes, the Egyptian queen as pensive and noble rather than seductive and dangerous.

I found women’s spirituality amidst patriarchal religious rule to be the most fascinating element of the show. The most striking encapsulation of the intersection of domesticity and spirituality lies in Andrea della Robbia’s terracotta relief of Mary and Jesus with holes for jewelry, so mothers could educate their children about religion and inspire closeness through play. I almost missed this piece, hung high, but it was the linchpin of my appreciation of the exhibit. The tactile nature of this piece, meant to literally be held close and even played with, invites us to consider what art is for, and how it functioned in a time so different from our own.

Art was also a vehicle for women to engage directly with their religion, despite patriarchal boundaries. For example, women were not allowed to touch the Torah, but they could seek special permission to weave its intricate cover. Convent life typically offered women scholarly and artistic opportunities that were enriching for them and lucrative for the convent. Small paintings served as personal devotional objects that women could literally hold close at home.

But hands-on, intimate expressions of spirituality were not the only ways that women expressed their faith. Female saints and Biblical figures were also the heroes depicted in works of art. I was particularly struck by the grandness of Titian’s “Saint Catherine of Alexandria” (about 1567) praying to Jesus on the crucifix. Its setting in a dramatic, open-air temple with a sprawling night landscape just outside of the radius of her adoration shows her devotion as mystical and transporting—not intimate, but vast and powerful.

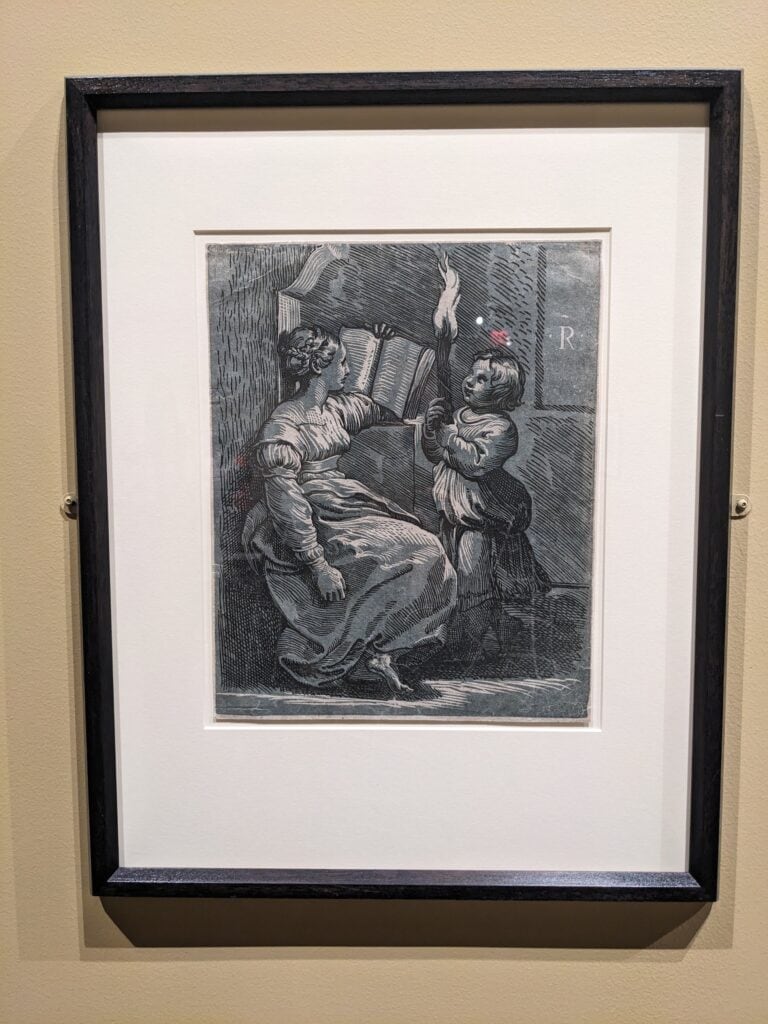

The exhibit does not claim to invoke a universal “woman’s experience” during the the time period, but as I pondered how renaissance women were living their lives, I started to wonder who exactly would be interacting with these pieces of art. I learned about Mary Magdalen as an inspirational figure, but where would a working class woman have regarded her? Only in church? Also, a charming “costume book” provides a wonderful record of different outfits worn by women in all social classes. But even though laborers’ outfits are depicted in the book, I imagine it’s highly unlikely that a laborer ever laid eyes on it. Similarly, those searching for evidence that the renaissance period was transformative for women—which they are prompted to do by its title—will find few pointed examples of that progress. Ugo da Carpi’s chiaroscuro woodcut “Sybil Reading” is perhaps the plainest depiction advocating for female enlightenment, showing a Sibyl, or “seer” representing female wisdom and intellect, reading a book in the light of a young boy’s torch.

My other wish for the exhibition is that the gorgeous music at the headphone stations would have been piped in throughout the galleries. These ethereally buoyant, mostly religious pieces by woman composers of the era would have enhanced the inseparable spirituality of the majority of the artworks on display, while surrounding us in women’s creation even if the painting we happen to be regarding was by a man. Nevertheless, to bask in this tactile history lesson and re-envision women’s lives during this period is an otherworldly privilege.