As someone who studies the various waves of feminism, feminist art, and feminist aesthetics, I was especially startled by Alice Procter’s assessment in Hyperallergic of “Judy Chicago: Herstory” at the New Museum, on view through March 3, 2023. Procter not only dubbed Chicago’s oeuvre “corporate feminism,” but she found it all surface, lacking “the depth, guts, the ambition, and potency of The Dinner Party.” Not surprisingly, her “dig” made me want to explore this survey even more. Either I had missed something substantial about Chicago’s oeuvre or Procter’s rebuff rather exemplifies a generational shift.

As it turns out, Procter, known for her “Uncomfortable Art Tours,” is on a mission to “decolonize” the artworld, a project that entails revealing the alarming backstories of portrait sitters and museum treasures, as well as inviting visitors to alert museums to object labels deemed “racist, colonialist/imperialist, classist, homophobic, sexist, trans-erasing, gender essentialist, and totally impenetrable.” While I sympathize with her concerns, I worry that inspiring spectators to “typecast,” rather than rewrite labels, elicits stereotypes. What art history needs most is an expansion of its cannon and a reconceptualization of its narratives, twin ambitions Chicago’s inclusive “Herstory” largely achieves. On this level, “Herstory” is not exclusively Chicago’s story, but “our” story.

Despite the various controversies sparked by Chicago’s radical collaborations such as “Womanhouse” (1972) and The Dinner Party (1974-1979), I have long appreciated her having initiated, publicized, and perpetuated collective artistic practices, even though her contributors have not always felt properly accredited, appreciated, or remunerated. I would argue that contributors’ rightful demands for greater recognition rather reflects the fact that art-making is not (and never has been) a solitary affair, even if art history tends to characterize it thusly. To my lights, the collective nature of artmaking, and especially exhibition making, is one of Feminist Aesthetics’ key insights. That Procter deems Chicago’s output “nothing but surface” suggests that she fails to grasp the significance of “the fine art of doing something together.” Since Procter endorses The Dinner Party, her concern can’t be that Chicago is often singularly credited for artworks handcrafted by others. After all, collective practices are rarely true collaborations.

Even Chicago’s “minimalist” artworks convey collectivity, though with manufacturers, walls, and environments. Not only did she transform car hoods into canvases sporting vivid abstract imagery (1964), but she installed Rainbow Pickett (1965), a wall-supported fence years before Richard Serra’s Prop (1968), and 10 Part Cylinders (1966), an environment of cylinders ranging between five and eight feet tall, more than five decades before 2022, Serra’s singular ten foot tall solid steel cylinder.

© Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

New York. Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Purchase 2007 (The Second Museum of Our Wishes) MOM/2007/149.

Photo: Donald Woodman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Matthews polyurethane paint on stainless steel

118 3/4 x 132 x 118 3/4 in

© Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

New York. Jordan Schnitzer Family Foundation

Four decades before Chinese artist Cai Guo-Qiang (of Beijing Olympics fame) gained fame for staging fireworks as his art, Chicago presented multiple colored-smoke atmospheres (1969-1972) in sites ranging from deserts to museum courtyards. Immolation (1972) features artist Faith Wilding posing as a Buddhist monk protesting the Vietnam War. During lockdown, Chicago reinvestigated this practice by photographing colored smoke trapped in spaces bordered by fences and walkways.

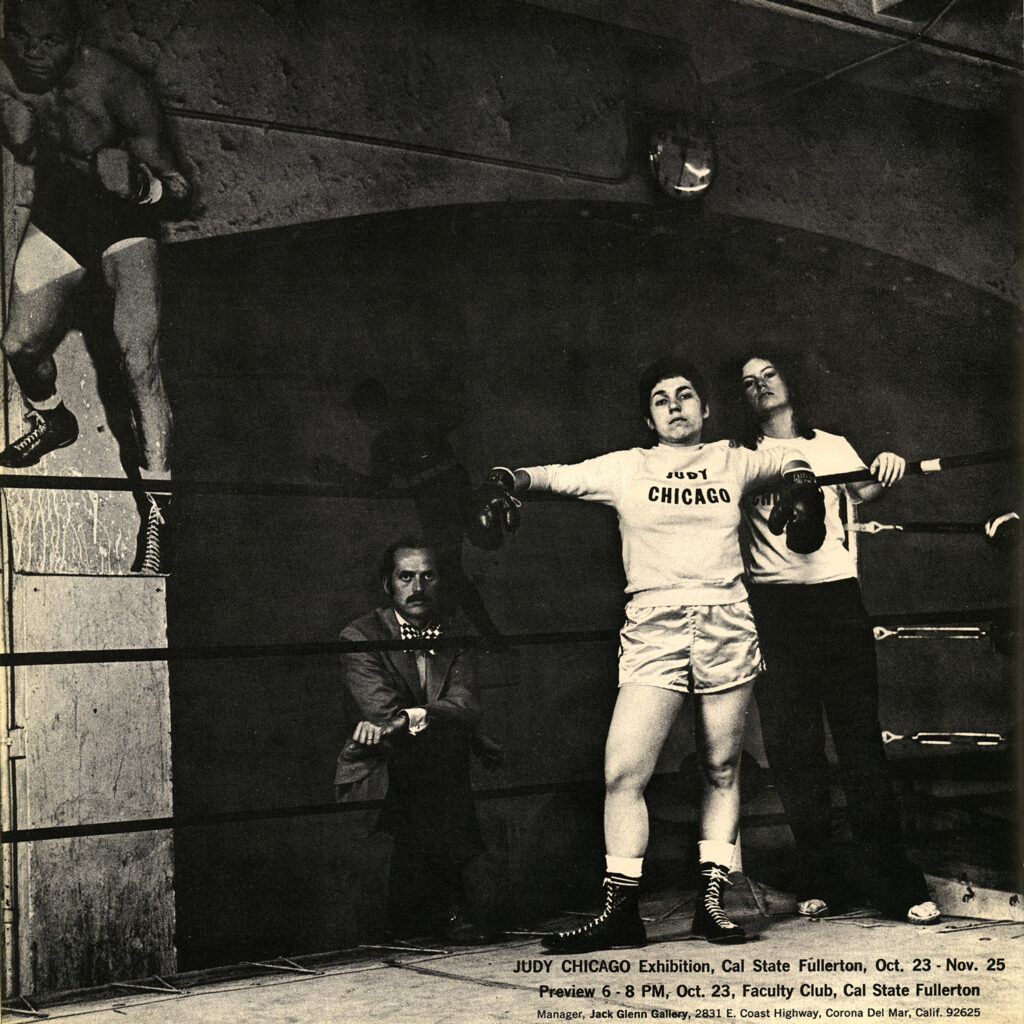

Collectivity is vividly present throughout this exhibition, beginning with photos, ephemera, and videos from the early years of the Feminist Art Program, first at Cal State University-Fresno (1970-1992); then Cal Arts (1971-1976) in Valencia, north of Los Angeles; and finally, the Feminist Studio Workshop (1973-1981), an independent art school that evolved into the Woman’s Building (1975-1991) in downtown LA.

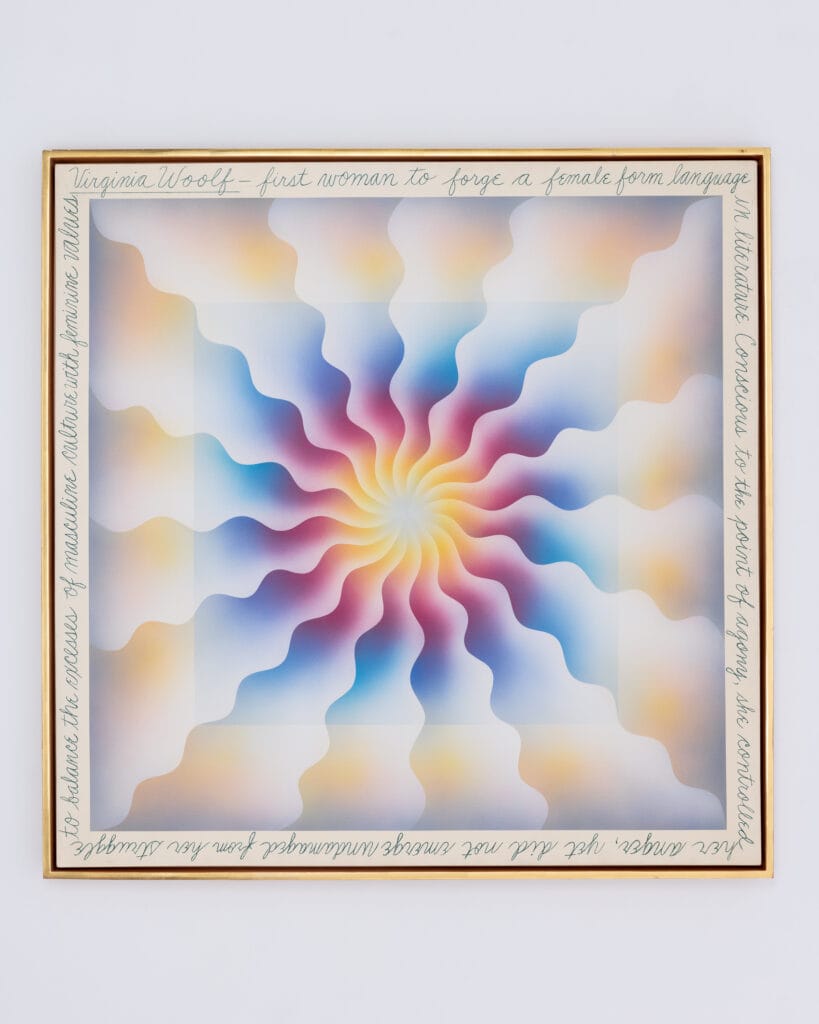

During this period, Chicago merged the beauty of lifeguard buoys with Beech Nut’s colorful Lifesavers to create Pasadena Lifesavers (1969-1970). Within a few years, this imagery evolved into “central core imagery,” pulsing pastel forms evocative of blooming flowers, ecstatic vulvas, bursting stars, germinating seeds, or butterflies in flight. Although Chicago’s painting Virginia Woolf (1973) doesn’t resemble Virginia Woolf’s place setting at The Dinner Party, it offers a powerful example of “central core imagery.” The handwriting surrounding this starburst remarks, “Virginia Woolf- first woman to forge a female form language in literature. Conscious to the point of agony, she controlled her anger, but did not emerge undamaged from her struggle to balance the excesses of masculine culture with feminine values.” No doubt, Chicago too was engaged in forging a female form of imagery in art.

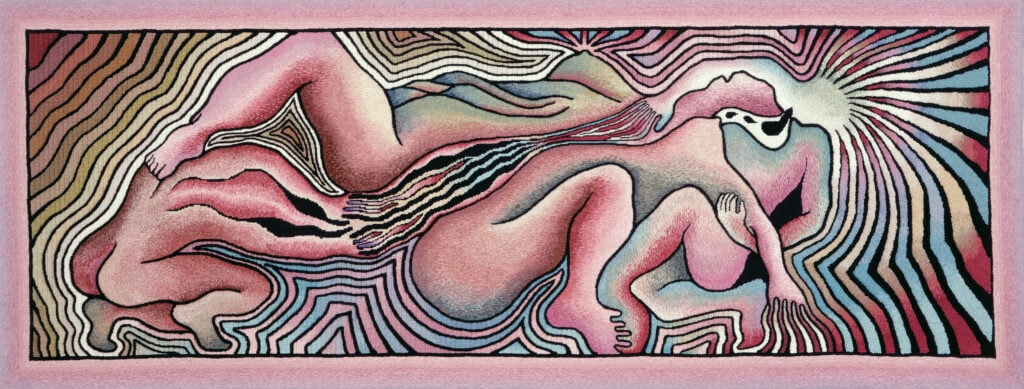

Given people’s tendency to erroneously typecast all of The Dinner Party’s 39 plates as “vulval” imagery, the availability of exhibition copies of drawings of the plate’s varying imageries here offers a corrective. Chicago’s The Birth Project (1980-1985) continued The Dinner Party’s collective approach. This time, however, she worked collectively with dozens of “needlepoint artists,” selected from across the United States, a practice she returned to at the millennium, when she started producing modest needlework paintings that wryly illustrate core values such as “a chicken in every pot” or “welcome with open arms.”

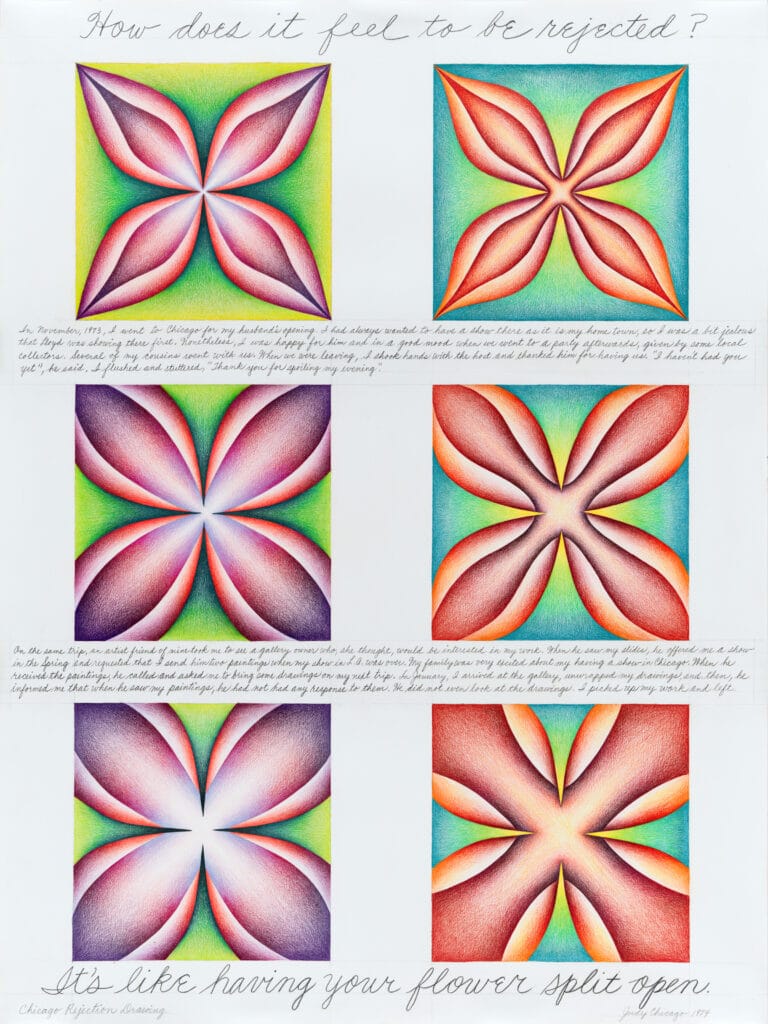

This survey also includes multiple playful participatory games (1965-1967), a surprising Artforum image advertising a solo exhibition, discrete Clitoral Secrets (1975), and several petite porcelain goddesses (1977). By contrast, complex written narratives accompany series’ components inspired by important questions such as How Does it Feel to be Rejected? (1974), Did You Know Your Mother had a Secret Heart? (1976), How Will I Die? (2015), and a 2017 series that seems to ask “How Can We Ensure Greater Species Protection?”

Prismacolor and graphite on paper. 40 x 30 in

© Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS)

New York. SFMOMA. Gift of Tracy O’Kates

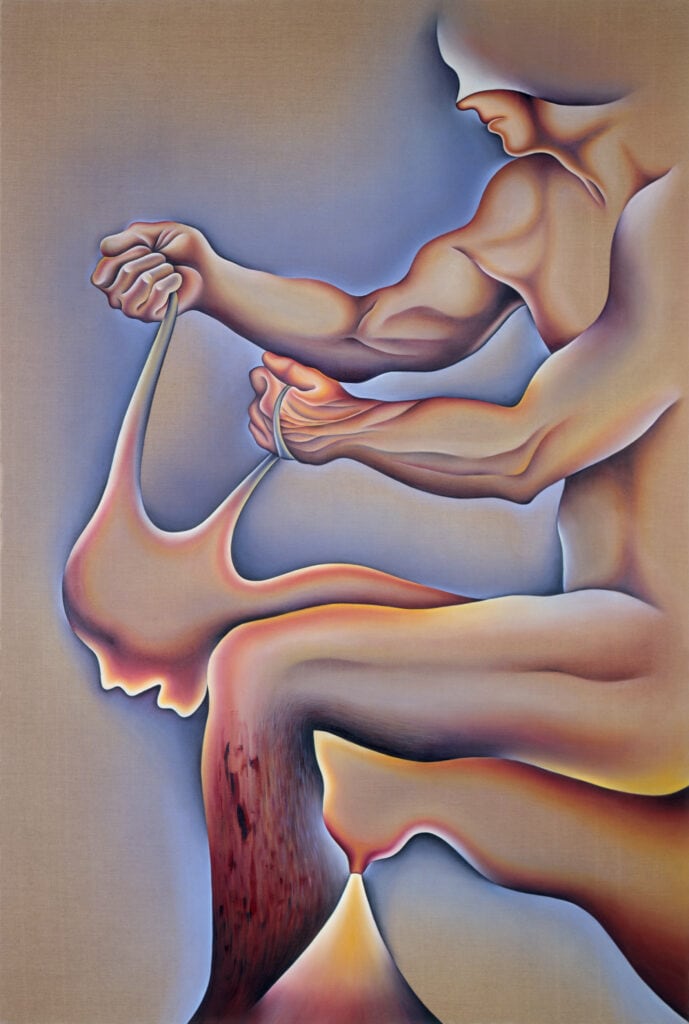

In 1983, Chicago entered a new phase with her “PowerPlay” series. Apparently inspired by obscene acts of violence against women, she turned her attention to visual representations of masculinity, leading her to draw from life models. She even traveled to Italy to study male figures in Renaissance art.

Similar in spirit to her joint-ventures with female students and colleagues, “Judy Chicago: Herstory” includes “The City of Ladies,” a phenomenal collective exhibition situated amidst her survey. Eleven of Chicago’s banners, originally conceived for Dior’s Spring 2020 haute couture catwalk, accentuate “The City of Ladies,” a remarkable assembly of 98 objects by 79 visual artists, filmmaker Maya Deren, poet Emily Dickinson plus authors Annie Besant, Simone de Beauvoir, Margaret Sanger, and Virginia Woolf.

Spanning eight centuries, “The City of Ladies” begins with a posthumously-published Hildegard von Bingen illustrated manuscript (1210), an Artemesia Gentileschi painting (1630), and a Maria Sybilla Merian hand-colored engraving (1705), and ends with 75 20th-century avant-garde collages, paintings, photographs, and sculptures. Of special note is the inclusion of both Maria Longworth Nichols Storer’s Vase (1881) and Mary Louise McLaughlin’s Ali Baba “vase” (1880), both on loan from the Cincinnati Art Museum, which also lent Elizabeth S. Clarke’s Star of Bethlehem (1849) quilt.

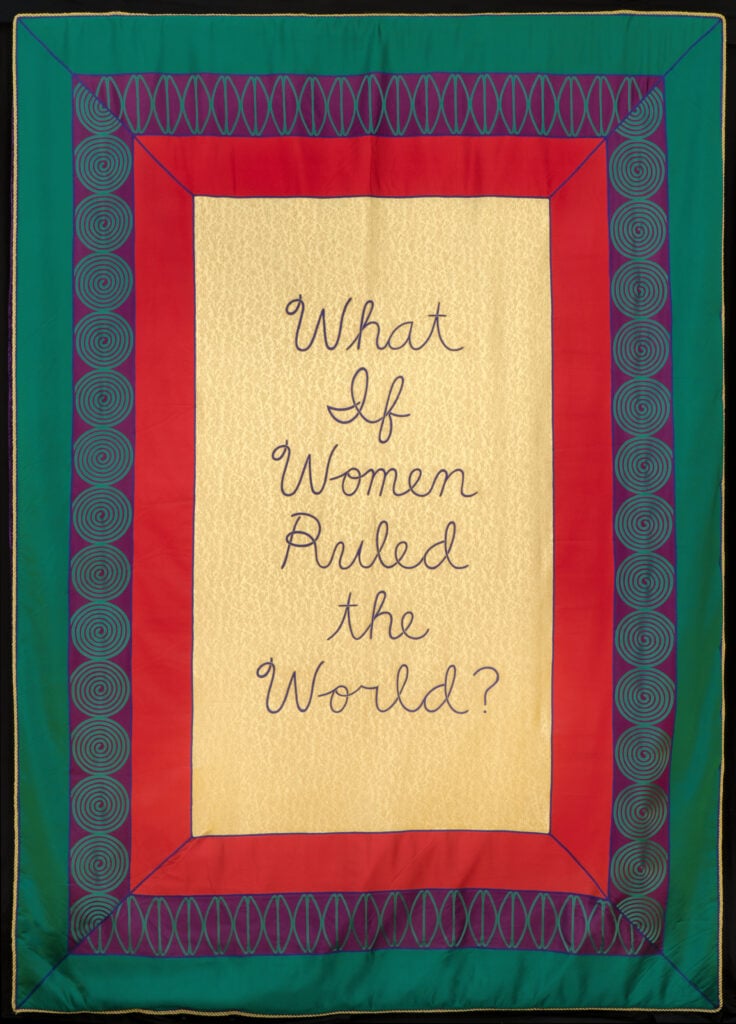

Last but not least, the New Museum’s Sky Room (on the top floor) features The Female Divine (2022-2023), part of an online collaboration with Nadya Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot fame. Visitors from around the world are invited to respond to the eleven questions embroidered on the banners from her 2020 “The Female Divine” series. Museum visitors’ videotaped responses are transcribed and then embroidered over the participant’s image on one of eleven “digital quilts.”

In truth, there is a lot (perhaps too much!) to experience here. “Judy Chicago: Herstory” leaves visitors with a solid understanding of the variability, effervescence, and ingenuity of art made by women over the past century, not to mention Judy Chicago’s expansive vision of art history’s future.