At Indian Hill Gallery,

September 8-October 28, 2023

Indian Hill Gallery’s “Autumn Annual” is a big show, though constrained by the gallery’s square footage to be modest in size. The works are excellently displayed and there is a very fine catalogue. The show has brought together work by two well-known area artists and teachers, Frank Herrmann and Rob Robbins, nominally around the theme of trees, but more substantially linked by the two artists’ thoughtful (and sometimes ravishing) engagement with what makes up an artist’s relationship to nature, and even what makes up our own.

It’s hard to miss the beauty of Robbins’s canvases. His colors are as shimmering as stained glass (in her catalogue essay, Ruth Meyer calls attention to his “experiments with newer synthetic paints that are brighter and more radiant” than previously on the market), and his draftsmanship, whether in paint or with graphite (or an eraser) can be mesmerizing. His work is most challenging in its subject matter, perhaps—and perversely—because it is so ordinary. He paints the crush of vegetative life, an over-abundant world in unremarkable locales. Unlike some American landscape traditions, there is nothing ostentatiously remarkable about his subject matter; Robbins says that he focuses on “small spaces portrayed on a large scale.” The harder we look, the more specificity drops out of his work. They depict the lushness of spring in a palette more typical of fall. In a single work like “Entanglement” (2023), for example, the foreground is constructed out of the cooler color scheme of twilight while the background has the warmth of late morning. The whole effect seems familiar but hard to place. It is designed to be at least a little disorienting, and perhaps even gently hallucinatory. If there is a central focus to “Entanglement,” it is the base of a tree which is being swarmed by an army of leaves climbing inexorably up—though they might also be gushing out of it in a partly green, partly blue cascade.

There is an ongoing drama in Robbins’s work about whether things are moving inwards or moving outwards. In her catalogue essay, Ruth Meyer applies this question to the situation of the viewer who is being drawn in; she quotes Robbins, who suggests that the dense foliage seems to “engulf the viewer, and the viewer must push their way through to the ground before them, and then to the horizon.” Unlike, say, the tradition begun by the Hudson River landscape painters, there are no pathways to suggest where we should go or how we got there or even the reassuring scatter of pine needles and boulders to root us to the same ground as the subject of the painting. There is no horizon line to put us at our ease. It is not clear whether we are being drawn in so as to better orient ourselves or being kept out. If we took that step forward, what would our foot meet?

“Acculturation” (2017-2023) is perhaps the major work in the show; at 11 feet long and 6 feet high and almost incalculably bright, it is certainly the attention-grabber. It fully displays Robbins’s status as a master colorist; it can seem like the work of a Fauvist on acid. The title suggests that in it, we might be prepared to see evidence of one culture being absorbed or modified by another, and he has said of his work that it raises “issues relating to acculturation, social and political conflict and compromise, resource management, suburban sprawl, and the persistence of nature.” Though I’d be perfectly happy to see evidence of those concerns, I must confess that I don’t. The painting seems like a beautiful curtain, designed to keep us at a distance, perhaps from the source of bright light that streams from the background. It is gorgeous but not restful; there is almost something mystical in its view of nature.

There were several masterful drawings by Robbins in the show, which I took to be finished works, not studies for paintings. “Further than Anticipated #2” (2023) is a glance into a forest that is both backlit and front-lit. (I can’t help out much about the title except to note that it gives us the sense of an ordinary walk that has gotten slightly out of control.) We see trunks but neither the bottoms nor the tops of the trees. Things are once again both ordinary and strange. Without wishing to invoke the theme music from X-Files, in some of the works there is a painted slice, a visual break in the continuity of the surface, a sense that we’re not really looking at a representation of a natural scene at all. This seemed partly clarified by the most overt (and wonderful) example, “Further than Anticipated #1” (2023), where what we see is made apparent only under or through a second visual field—we’re seeing tree trunks and the reflection of other tree trunks. If we want to naturalize it, it’s perhaps what one sees looking through a car window, bearing in mind that the car window is also reflecting back a second scene behind us. I prefer to think of it as a reminder that even our first-hand experiences tend to be second-hand ones: it is hard to see nature without seeing it through the filter of the infinite ways humans have looked at nature over the course of time. Millennia of human perceptions have helped shaped what we think of as nature. Our seeing of things also creates those things—which is perhaps one way that the political and eco-conscious level that the artist spoke about comes into play.

Frank Herrmann’s part of the show is a collection of paintings of single, aged trees against various backgrounds accompanied by haikus of his own writing brushed onto the canvas. The trunks, we are told, belong to actual trees he has seen in his travels to Japan, Greece, and Croatia. In truth, though, they really could all be the same tree: it is monumental in size or proportion, gnarled and partly decayed (though importantly still alive), leafless, and mostly with the tops of their central branches trimmed. Sometimes we see the ways the tree is rooted to the ground and sometimes we don’t; sometimes we see the tops of the bare branches and sometimes we don’t. It is frequently sculptural and occasionally loosely figurative. It is painted in great range of styles and techniques, sometimes appearing creepy like an Ivan Albright, sometimes scaly like a Phillip Guston, and sometimes with the joyful, colorful energy of a Charles Burchfield.

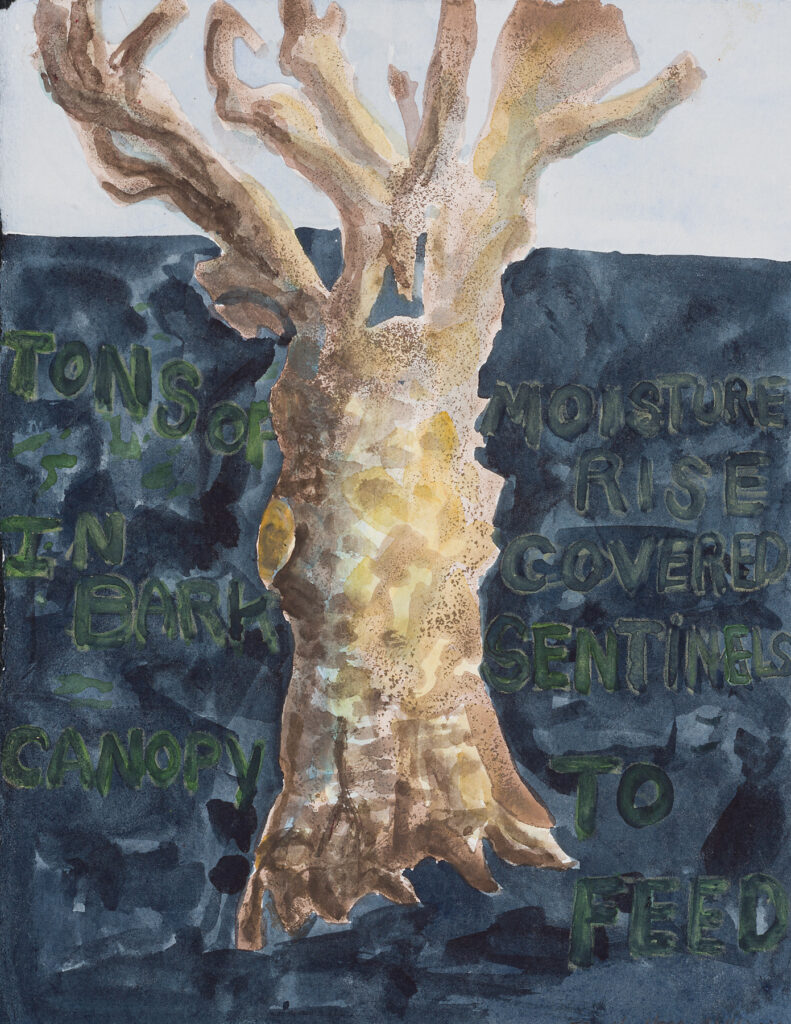

In the earliest work in the series, the haiku is written below the tree, like a caption, but as the series goes on, the text has invaded the canvas and surrounds the trunk of the tree in bold, though not always legible, letters. In “Tree Trunk/Haiku-1” (2018), Herrmann’s haiku sets out an important part of the argument he wants to put forward: “Tons of moisture rise/in bark covered sentinels/canopy to feed.” [I have taken the liberty of printing Herrmann’s poems in small letters—on the paintings, they are in all caps—and punctuated them as if they were each a single sentence.] The painting of the tree depicts its outer life; the poem suggests that there’s an inner life to be considered as well. In appearance, they are sentinels—statuesque, isolated, outsiders—but inside, they are doing mammoth amounts of work, raising all that water to nourish the canopy. It is interesting that none of the trees actually have leafy coverings, but the work of the xylem and the phloem goes on anyway. Herrmann does not propose that he is an arborist—he has no particular interest, for example, in how the soil feeds into the tree or the role of sunlight or rain. What counts is that we distinguish between the inside and the outside, and can come to respect the inside even if we are always, relentlessly, on the outside.

On the one hand, Herrmann wants us to able to see that the trees are sometimes reminiscent of human beings—sometimes dancing, sometimes threatening, sometimes like a hand reaching up out of the earth to feel the air. But on the other hand, he is careful to remind us that the trees we are dealing with are paint. On “Tree Trunk/Hailku-7 (for Jake Berthot)” (2020), he has written “What matrix is this/erecting light scrims in/verdant lushness of paint.” The painting’s shapes create scrims, indeed our whole world may be nothing but scrims—semi-transparent screens through which we make out what is going on beneath them—not out of nature or water or soil, but out of the “verdant lushness of paint.” The fundamental building block of what we see is the beauty of paint, a lushness even greater than the lush representations of sky and soil. It’s also a reminder that all of this wonder of nature is a show of sorts, an exercise in curtains and scrims, and when we’re through examining the shadows of our world through them (perhaps in a Platonic way) we have to come back to appreciating what they are made of.

Herrmann’s paintings are more complex than his watercolors, not just because of their larger size but because of his choices of media. Several have elements of collage added, typically scraps of photographs printed on canvas that have been painted over. They generally use acrylics but also sometimes markers, oils, and charcoal, and the paints are used in a range of ways. In “Tree Trunk/Haiku-2 Olympic Tree” (2020), Herrmann has applied the paint in a variety of ways and for a variety of effects. The top register reads like a conventional landscape, with a lawn in the background and black balls of distant trees. In the foreground, directly beneath the tree and to one side are densely patterned sections like a superior piece of decorative art. Herrmann enjoys bringing both to bear upon each other (as did Matisse).

This painting offers another particularly interesting haiku: “Olympian bark/the singular contestant/scars like earned honors.” I understand the praise for the ragged bark as Herrmann turns our attention to the valiant experiences the tree has endured to get here. The phrase “the singular contestant” is striking and more puzzling. A “singular” contestant may be an unusual one. But it may also be “singular” in that the tree faces its trials alone, competing perhaps by itself and perhaps with itself. It has a history of which we can’t be sure.

The collage elements are mostly part of the background. A young woman has her back turned towards us and somewhere in her distance is a collaged blue car. We can’t make out the figures in the car, though a woman’s hand is holding a pink flower out a rolled-down window (another part of nature’s aboveground world). Collage technique had an important resurgence in Pop Art, where it was used to offer an alternative to the subjectivity of the artist’s brush and mark, but also introduced questions about the clichéd and commercial nature of printed culture. The young woman and the car are among the most cinematic elements in these paintings in a way that might make us distrust what we’re seeing. But I also think the purpose of the collaged elements here are to encourage us to note that we can see no other human faces; the tree and the foreground are only being seen by the artist and by us. These are the only witnesses that matter.

Like The Olympic Tree, “Tree Trunk/Haiku-4 The Dubrovnik Tree” (2020-22) is another specific portrait, though it continues to explore the issues of the series as a whole. The haiku proposes a question: “Disorient space/what shroud obscuring is this/cloaks the massiveness.” What indeed? What cloaks the tree’s massiveness? The answer, in part, is the bark, which is never scalier than in this painting. But the poem also suggests that it is the disorientation of space itself, the distance between the painter and his subject, that helps obscure the tree’s heroic proportions. The artist’s very glance enables the painting to be made but also inevitably distorts it. The obscuring shroud matters more in this painting than in several of the others because Herrmann has gone to such lengths to try to reveal the inner nature of this tree. While not exactly hollow, the tree has a considerable amount of its insides revealed. It’s not clear that this anatomy is reassuring. Inside the shadow within the trunk, there might lurk a crouching figure, and below it, a face. There is massiveness, but also monstrousness.

This tree sits in a sort of architectural space defined by a series of straight lines and angles. It might be in a shrine of some sort, or perhaps in a theater. Once again, there are collaged photographs, and once again, they feature humans whose backs are to the tree. What we see belongs only to us. We are standing at the artist’s elbow, and have the chance to see what the tree is, and what’s inside it, a chance perhaps to see ourselves. It’s our moment.