THE FLOWER PRINTS OF KATSUHIRA TOKUSHI

The Dayton Art Institute

On view through September 18, 2022

Hiroshige. Kuniyoshi. Hokusai. These are a few of the revered masters of Japan’s most celebrated era of woodblock printmaking. Active in the 19th century, these artists’ works –featuring landscape views and the “pleasures of the floating world”–were collected avidly not only in their home country, but abroad. Although attributed to a single hand, their intricate prints were in fact the product of a complex network of artisans and publishers. From the paper makers to the woodblock carvers, these works were a collaborative endeavor.

In singular contrast to this tradition, the prints of Katsuhira Tokushi (1904-71)

were almost entirely the work of one person. [NOTE: In Japan, as in China and Korea, the first name follows the family name (surname).] He was the designer, the woodblock carver, the printer—even at times the papermaker. In this way, Katsuhira comes closer to the traditional Western ideal of the solitary, inspired artist who both conceives and creates his work. Of course, that ideal is a bit of a myth, as there are countless examples (from Raphael to Jeff Koons) of works created by workshops.

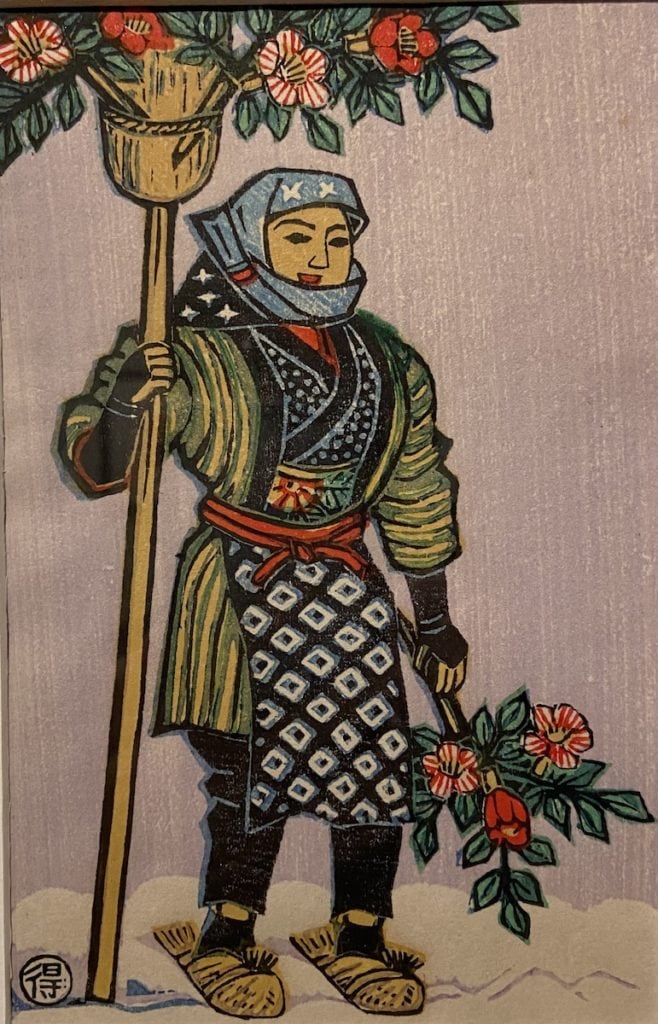

The Flower Prints of Katsuhiro Tokushi provide a classic example of work by this rural 20th century artist. Like Katsuhiro himself, the core prints–Twelve Works on Flower Selling Customs (1959-1961)—are modest in scale and presentation. The works reflect Katsuhiro’s self-taught skills, as well as his commitment to the humble subject matter of Akita City, his homeland in northern Japan. Eventually, many of Katsuhiro’s simple woodblock illustrations of traditional scenes from life in this remote province were used in Akita Almanac, a 1966 publication.

Carr

The exhibition, although marketed as a “Focus Exhibit,” is largely invisible to the average visitor. Buried in the depths of the museum’s Asian galleries, this display is presented with little fanfare—but is still a winning installation. Bracketed by a few larger works featuring floral designs—a gorgeous folding screen and a luxurious brocade kimono—these mid-century prints provide a fresh counterpoint for visitors. The prints are simple and direct, but appealing; each features a single female figure, dressed in native clothing, and representing a different month. Ideally, we see the flowers that might bloom in the corresponding month.

Throughout the spring months, the main figure is accompanied by flowers such as iris, lotus, and chrysanthemum. Despite Akita’s challenging, long winter months, the artist perseveres inventively, sometimes using artificial blossoms for the months representing this bitter season. Ironically, this visitor found the examples from December, January, and February to be the most charming. The drifting snowflakes, the bundled figures, and the lively scenes made the harsh season disarmingly appealing.

Regardless of the month, the prints were unaffected and direct—engaging characteristics for the modern sensibility. They have none of the complexity or artifice of his more famous print predecessors. Likewise, the “origin story” of the artist is unpretentious. The possibly apocryphal tale is that—inspired by wood-block prints in the newspaper—Tokushi cut his first blocks from wood purchased from a clog-maker, and sharpened the metal ribs of an umbrella into a cutting tool. For paper, he used the washi that his father made. Nonetheless, by age 25 the young artist had two prints accepted at a print exhibition in Tokyo and was soon able to devote himself fulltime to printmaking.

While Katsuhira Tokushi might be seen as an outlier, his embrace of all steps of the print process reflects several other trends in Japan in the first half of the 20th century. In fact, there is a name for these types of prints in which the artist has a hand in every stage of printing: sosaku hanga or literally, “creative prints”. Associated with new interest in artistic self-expression, the movement was championed by a subset of mid-century Toyko-based artists. Earlier in the same century, a rising interest in folk art (mingei) traditions echoed Katsuhira’s commitment to simple forms and common subject matter. It is possible that the self-taught artist was initially inspired by the so-called “Farmers’ Art Movement,” promoted by Kanae Yamamoto (1882-1946). A socialist utopian who hoped that everyone might become an artist, Yamamoto at the least introduced the idea of the arts as something that anyone, regardless of training, might try.

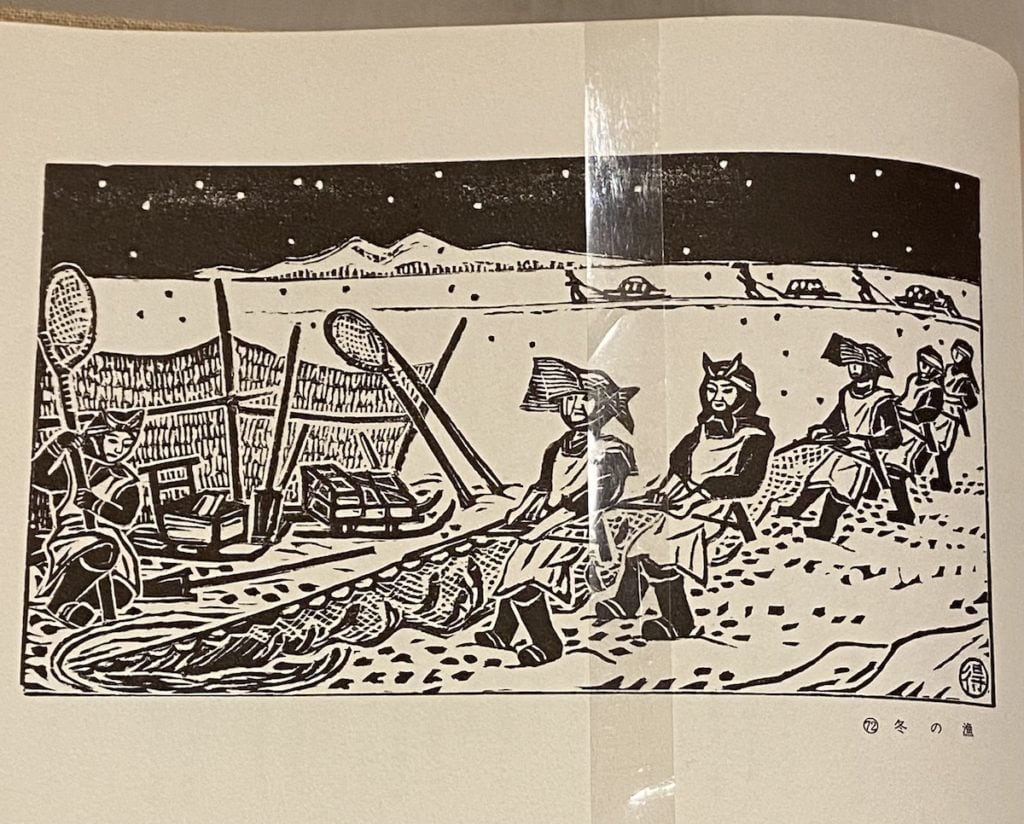

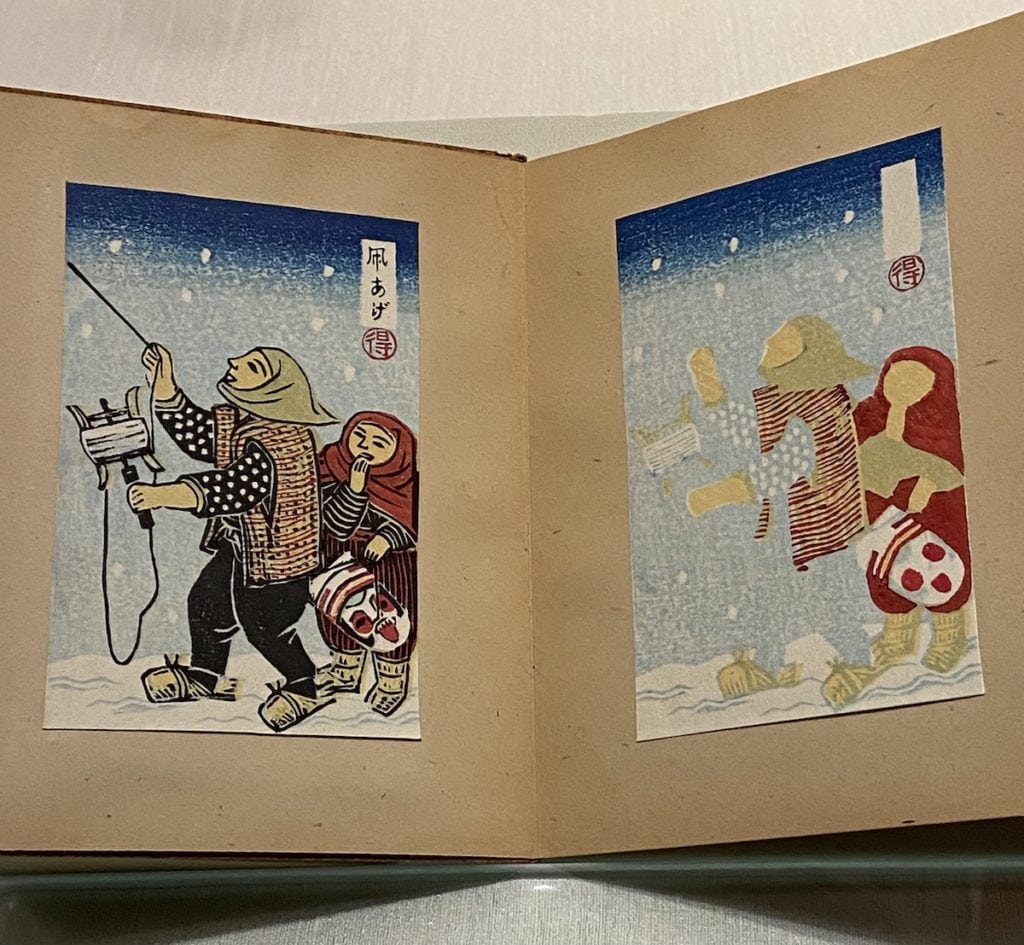

Printing Process. c. 1960. Private Collection. Credit: E. Carr

Katsuhira was a by all accounts a quiet, self-effacing man who called himself an artisan and did not seek honors. He was, however, anxious to spread his knowledge and published a folding book entitled Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Picture Book of Printing Process, a copy of which is included in the exhibition. The booklet is a marvelous didactic piece that illustrates the multi-block print process of laying down separate colors using different blocks. The exhibition helpfully displays the reverse of the book panels with large-scale reproductions, chock-full of graphic text in both Japanese and English.

Unlike the courtesans of many earlier ukiyo-e prints, the women featured in Katsuhiro’s prints seem approachable and authentic. Although clearly made appealing in design, the images provide a window into a humble rural world that was nonetheless beautiful. It’s a vision worth reflecting on—and visiting.

Eileen Carr