Facing and Defacing It:

Matthew Zory is—and almost was—the Assistant Principal Bassist of the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra (he will retire by the end of this summer). He is now fully devoted to photography; he has exhibited widely (at Manifest and the Taft Museum, among other places) and in 2017 published Through the Lens: The Remaking of Cincinnati’s Music Hall. But the works in this current show are the product of, and his responses to, the pandemic. For Zory, the pandemic was the occasion for a deep dive into oneself, a time without our customary distractions of work, play, or other people. If we strip away our jobs and our households, cut out Netflix and Uber Eats, what did we find ourselves left with?

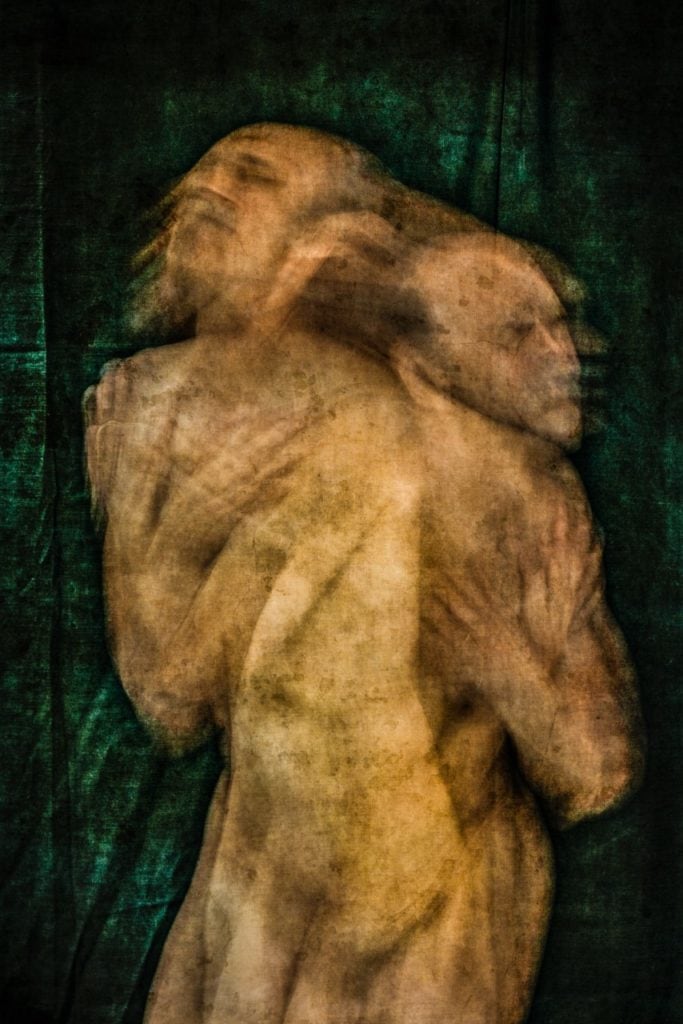

Zory expresses his answers in a series of photographic self-portraits. In all of them, he is nude. He exposes himself in a shallow space with a black or lightly textured dark background; his photographs have some resemblance to Goya’s etchings. What light there is illuminates his face, arms, and torso, to the waist or to the knees. No figure stands firmly on the ground. Somewhere between the taking of the picture and the final print, Zory has added layering that gives the image what he calls a “fresco feel.” Certainly they look sculptural or stone-like. Nonetheless, they are highly expressive. The figure’s arms are stretched upwards in prayer or struggle, or crossed over his chest, perhaps in shame or just as a way of being at home with himself. And though they may be designed to look like stone, the figurative presences are also highly fluid: in virtually every picture, one image of himself segues into another, like double exposures only done in a single take in which he pauses twice to fix two visions of himself. These visions are connected by a blurred arc of his body in motion, moving from one pose to the next.

The majority of Zory’s photographs feature two images of himself that ask to be read in light of each other, though it is not always clear just how. Since in our culture, we are trained to read from left to right (and since the two figures are not free-standing but are linked by the umbilical cord of the blur), it is hard not to read them as sequential, a sort of call-and-response. Other readings, however, certainly allow the two to be read as complementary (or conflicting) simultaneous psychological states, an acknowledgement that we can be more than one thing at the same time. At the core of the show is a desire for the artist to present a range of feelings about himself, particularly under the pressure of our response to a disease that keeps us from our normal lives and our everyday associations with others.

In #2, for example, the figures’ arms are folded over his chest, a central if ambiguous gesture throughout the series. Is it a sort of hug of self-love, or an expression of shame? Is the figure literally staying in touch with himself? Perhaps even more fundamentally, these images suggest a complex interplay between the revealing of the naked self and a desire, however fruitless, to cover that self up. It is even harder to be sure what they suggest as a pair. Do we read the figure on the left as a person lost in prayer, or does the slight hint of a grin suggest almost the opposite, a figure who does not see himself in need of praying? The second figure—as is almost always true, the shorter one, the one further away from us, the one in part obscured by the first—seems more plainly unhappy. Again, it is hard to say whether we should read them as sequential—are they tied together by something like a narrative?—or as coexisting, the artist suggesting that for better or for worse, he is both these things?

Sometimes it seems as if the images are meant to be read as sequential. In #5, for example, one version of the figure sits against a textured background that is highly suggestive of a staircase. The figure on the left is leaning against a wall looking out at us (it will often be very important just who the figure can and cannot face), perhaps at rest or perhaps challenging us. The figure on the right is doubled up, covering his face with his hands. It could be in tears, or it could be out of shame, or it could be a step backward from the figure on the left’s boldness at staring—perhaps even glaring—at the audience. They are connected by whoosh lines, as a drawing in a comic book designed to suggest motion might be. In any case, the one on the right seems like the second thought. Others are more interwoven, like #7. The figure on the left is sorrowful and looking out and up, as if in prayer. The figure on the right seems to have his eyes closed and is turned away and down, as if unworthy of prayer. But though it seems to be about the limitations of a prayerful attitude, the figure on the right has elongated, almost monstrous fingernails, suggesting that it might be the more dangerous of the two, though it’s not easy to tell just who is meant to feel endangered.

In some of the pictures, the source of danger is not just internal and psychological. In #6, for example, the foreground figure has its arms outstretched, possibly in a greeting though the expression on its face seems sour rather than welcoming. The background figure, however, is blurred, beginning to throw up one hand as if startled and trying to protect itself. And with good reason. Superimposed on the photograph above it is a long, angled straight edge, and above that, what looks like pincers of broken glass. In all, it is a little like a guillotine blade descending which one figure has seen or sensed, and the other seems utterly unaware of. In Zory’s world, sometimes there are real things worth our terror. The figure who doesn’t recognize the danger keeps his identity, while the one who sees it has shaken off his identity into a mere blur.

The capacity to maintain an identity in the midst of pandemic is an important issue in this exhibit. What does it even mean to do self-portraits during a time when so many of the external supports to our identity are taken away? In #3, we see two figures apparently in a line behind a third. There is a suggestion of a wall behind them from which they may be emerging. Perhaps they are part of an endless procession of selves. Self-replication is a frequent trope in gothic terror—think of Dr. Who’s daleks or the sorcerer’s apprentice and his infinite, identical broomsticks. The figures in this one face us but are expressionless, though the middle figure has perhaps locked eyes with us. It seems both accusatory and mysterious. There is almost nothing we can know about them, which is a source of uneasiness in itself.

My favorite photographs at Zory’s show are a grouping of three related images (#4, #12, and #13) in which the second figure is hardly visible and the primary figure seems to be struggling to emerge from a transparent envelope, a tent of some sort which sometimes looks an article of clothing and sometimes look like the sorts of plastic bags we are constantly being warned against allowing children to play with. In #4, for example, he is struggling hard to escape from something that seems so inconsequential. These three are the only ones where the figure has its mouth open, as if calling to us, but the face has been reduced to its openings, which turns out to be ghastly; we see dark pits for the eyes, the nostrils, the mouth crying out. The artist’s moustache is gone, as are the definitions of his musculature and the nuanced expressions on his face. It turns out that terror is far less detailed and individualized. Accompanied by his fears, he faces us directly. Is the figure the victim of what frightens him or is he trying to frighten us? Is the terror something we ought to be feeling too, or are we watching someone who is caught up by his own mind-forged manacles, as Blake once put it?

In #13, the figure, now presented in a greenish monotone, is once again struggling with the transparent envelope. But this time, the figure is losing. There is nothing left of his face or its expressiveness. In wild motion, the transparent cape catches the light. This creates thin bright streaks that seem like lines drawn across the head and body, opportune and thought-provoking scribbles. The face is gone entirely, the arms are gone, even the signs of his masculinity are gone—indeed, alone of all the others, there is something feminine about this figure. Though the figure has been literally defaced—defacing, as we know, the self-portraying artist—he has left in its place the artist’s marks, the lines that we recognize as expression and even intention. The self is a creature that is deliberately made and can be deliberately unmade.

Matthew Zory exercises throughout this show a tough sort of self-regard. He suggests that he is looking at himself so intensely that the self might just disappear. The pandemic has led us all into long conversations with, and about, ourselves. Those conversations partly reveal and even make ourselves. But there was never any guarantee that the conversations would be pleasant or gratifying.

Wash Park Art Gallery, April 8-July 16, 2022

“Matthew Zory’s photography at Wash Park Art was some of the best I have seen for some time. It was not at all what I had expected from him and I was fascinated and amazed. It is photography I will remember…. Your review was most welcome. I found it meaningful and an excellent read.”

Mary Heider