Looking back historically, one sees that Post World War II critics and curators endorsing the trends of expressive experimentation emanating from New York as the mechanism of modernism in the visual arts, eschewed figurative and narrative representations and the artists who employed these elements as outdated and behind the times. Regardless of the critics’ blessing, many American artists continued to search for personal and national identity through landscape and social strata access. A definable movement that links self identity with a sense of place emerged. This exhibit presents a meaty smorgasbord of Ohio’s regional artists of the same post war era who not only continued to reflect this state’s diverse blend of urban life, agriculture and industrial cultures, but did so within the expression of their own unique stylistic language. Several works also assail social conditions of the common man, both the simple pleasures and the circumstances of poverty and exclusion.

The landmarks recorded in this exhibition of Ohio regionalists range from inner city parks and main street store fronts to fringe neighborhoods, neglected fields and backyard rabbit hutches.

Several small works exhibited in block formation deal with outlying rural tenancy and farm landscape. Emerson Burkhart stands toe to toe in this set with George Bellows, deliberately arranged to contrast their treatments of a similar theme. Burkhart’s “Back Street Parade” depicts the early evening activity unfolding on the dusty road of an African- American neighborhood. The informal car parade having passed well into the distance, the local family is heading in for the evening, their two story residence flanking the right side of the composition. Most striking was the artist’s painted gray clouded sky with yellow and orange tinted white paint thickly squeezing out between the brush rendered clouds.

In Bellow’s image entitled “Street Scene with African American Mother and Children”, dated 1956, the female dominated family walks in the bright midday sunlight along the dirt alley. The blind side of a two story slat-sided house partitioned off by crude wooden fencing contrasts with the brilliant sunlight. Yards are littered with dry wood, weeds and a welding tank on wheels.

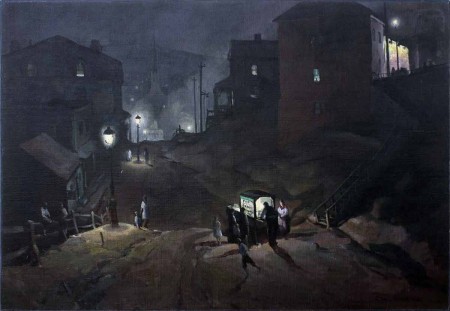

The work of Carl Gaertner is most impressive and featured throughout. The show is dominated by his dramatic “Popcorn Man” from 1930. In the foreground of this night scene, the lone vendor serves his product from his brightly lit cart, his customers animating the deeply rutted dirt road and the darkly silhouetted domiciles of lower class strata. Sparingly lit with tall gas lamps, the road leads from the outskirts into the heart of a small urban setting, where the single spire of a modest church pierces the night sky amid smoldering gases and tiny lights like diamonds on the ground. This painting is flanked by additional works by Gaertner which illustrate his fine big shape compositions. A great contrast on the left is “The Allegheny” where the yellow sky reflects broadly on the mighty iconic river, swirling past industry toward mountainous terrain, bearing steamboats and dinghies alike. Gaertner’s “The Ore Boat” is a thalo blue painting composed from the harbor of a lake port, and is so frosty that you can imagine your frozen breath before you. Both paintings place the viewer in touch with the harbor and river as an inland experience emphasizing the variety of commerce conducted to advantage here.

A striking group of gelatin silver prints capture dramatic moments pouring liquid steel in the Otis Steel Mill of Cleveland, Ohio. Dated 1928, these beautiful compositions by Margaret Bourke-White sear into our collective experience, the colossal vulcan processes wrought by man in the postwar industrial age. They are the only photographs included in the exhibit.

Several pieces expand on the pastimes and quotidian activities of the lower class populating the inner cities. Consider a group of Bellow’s lithograph images embracing inner urban life, teaming with Americans in a variety of modes: relaxing in a park and repairing a bicycle, a crowd swell in the urban underbelly, a sweltering political event complete with politicians and swooning women (“On the Sawdust trail”) and the purported insane kicking up their heels in the “Dance in the Madhouse, 1917”.

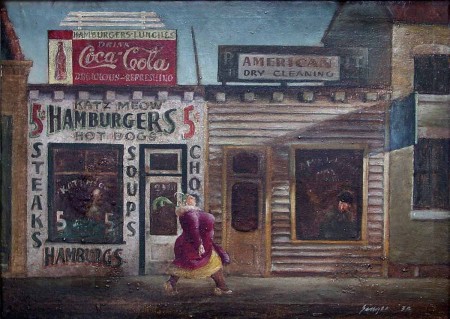

Life in small town Main Street is the subject of Clyde Singer’s smaller paintings with a marked proliferation of handpainted signwork. Midwest enterprises such as Grant’s Economy store serve as the setting of typical sidewalk scenes. Contrast the tongue-in-cheek episode at the Katz Meow Hamburgers storefront with the somber Republican Headquarters painting featuring the Knox/Landon ticket of the day. Singer’s larger oil painting “Wind on the Avenue” depicts a well dressed cast of women and applecheeked children fleetingly assaulted by a brutal wind gust. The location is marked by the brass sign work of a better shopping venue, Lazarus and Co., founded 1851. The capricious gale has blown open the wrap of a maternal Venus who dominates the composition. She holds onto her hat while her long scarf unfurls with a flourish. The artist contrasts her plight with the woman on her left whose sly expression confirms her flirtatious intentions by taking advantage of the situation to raise the hem of her skirt. Her plump upper leg is revealed, gartered mid-thigh with a dark stocking and a brief segment of rosy pink lace thus exposed.

Charles Burchfield, who spent his youth in Salem, Ohio, famously declared his identity as an ‘inlander’ in his journal in 1954, fusing his idea of self with an identity of place. His rural roots and fascination with seasonal weather patterns are revealed in several watercolors selected for this exhibit. “September Wind and Rain” alludes to the power of wind, its breath swaying every tree and weed in its path. The taller trees in the middle ground of this painting are assailed with three bouts of strong gale which not only bends their structure but transforms that section of the tree into sinister bat-like shapes, a graphic mechanism unique to Burchfield, visually depicting a formal change. In a larger watercolor entitled “Old Houses in Winter”, Burchfield’s composition of drab wood slat structures, typical of upper midwest construction are slouched gloomily on an icy street and animated only by a lone cur and a few blackbirds. The stylistically accented fenestration of the larger building, reflecting broken shards of grey sky and unseen structures, is unnoticed by the passerby trekking homeward with her basket of comestibles.

Several imposing portraits cannot be ignored. The expressions and forthright poses of the portrayed as well as the direct paint handling of the artist reveal the straight ahead philosophy of both with jarring authenticity. Clarence Holbrook Carter, born in Portsmouth, Ohio, paints a large portrait of Jesse Stuart. The writer is seated on a simple chair on an open front porch sited in a cornfield setting. He poses with knees wide apart, his large clodhoppers pushing the lower perimeters of the canvas. His gaze is unflinching.

John Hopkins contributed a group of well painted portraits: “Kentucky Mountaineer” is a sunbaked profile with a rifle. “Old Orchard” is an unnamed older man in a shaw sweater, seated frontally in a green orchard. The lush outdoor setting influences the flesh tones defining the facial features in this direct painting exercise. “Wings of Faith” by Yeteve Smith depicts an African American mother or grandmother with two children. The palms of her hands are placed squarely on the pages of the open Bible, on her lap, a confirmation of the power that the spiritual plays in their daily family life.

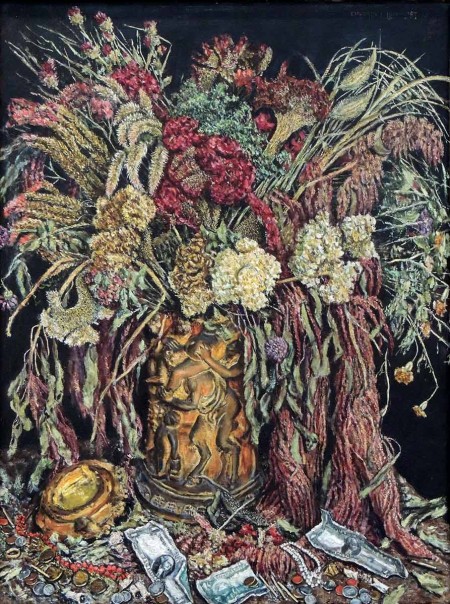

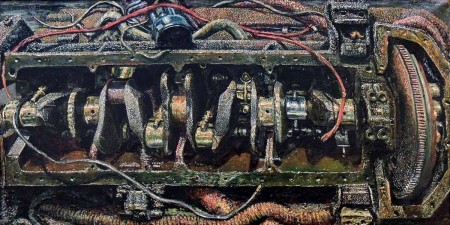

The right end wall is given to Emerson Burkhart. He shows three paintings. The surfaces of all three works are executed with textural, sculpted paint, literally writhing with energy. The center piece is “Engine”, a tightshot rendering of a cracked crankshaft as might be found on the repair table. One wouldn’t be surprised to find oil and scrap metal actually in this one. “Still Life” dated 1945, is a contradiction of the term. Crimson and gold cox combs, creamy hydrangea, a variety of common field weed and miniature carnations, broken to fit into the frame and fading fast are but a few of the specimens stuffed into his minotaur figured vase. Dollar bills, coinage, pearls and seed pods nestle among crumpled dried leaves on the tabletop. The crimsons, creams and greens play out in a variety of textures against an uncompromising black background. This deliciously painted decadence is a 20th century update on the decaying still life genre of the late Dutch period, encoded with the brevity of beauty and futility of wealth.

Finally, Emerson Burkhart himself smiles engagingly at the viewer in his self portrait entitled “Don’t be afraid of the Shape of Things to come” dated 1951. Frazzle-haired and beaming beneath a broad mustache, he holds a miniature profile of the irregularly shaped painting, possibly based on a small piano frame. A pocket timepiece dangles among several discarded traditional stretcher bars. He is smiling because he is in love with painting and the ichor of the paint gods runs in his veins.

Be assured that not all the wonderful artists and works are mentioned here.

This show is a unique opportunity to savor the flavor of Ohio’s sons and daughters who documented their sense of place and time.Their efforts can be seen as an early social realism movement while preparing the scene for pop art and other art trends of the 20th century.

Springfield Museum of Art through January 17, 2016

Marlene VonHandorf Steele, paints and teaches in Cincinnati Ohio