It was just before Valentine’s Day, when I saw the lavish “Bijoux Parisiens: French Jewelry from the Petit Palais, Paris” exhibition at the Taft Museum of Art, and how I longed for a wealthy beau.

During the reign of Louis XV (1715-1774), his court favored symmetrical designs and sparkling white gems.

The show features some 75 pieces of French jewelry, primarily from the early 19th- to mid-20th centuries. They are from the collection of the Petit Palais, City of Paris Fine Art Museum, Paris Musées. Supplementing the objects are designers’ engravings, which were made to claim creative ownership of the design, educate their apprentices, and market their work.

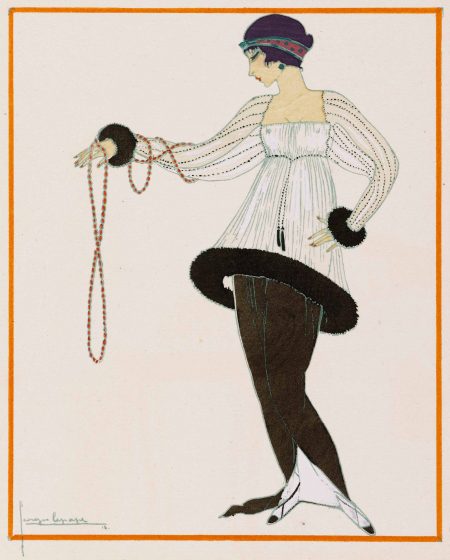

Furnishing a context for the pieces are fashion illustrations—fashion plates—that began to be published in the burgeoning number of women’s magazines appearing in early 19th-century France. Middle- and upper-middle-class women eagerly awaited the Vogues and Harper’s Bazaars of the day to see the latest fashions, fully accessorized.

1902, oil on canvas. Taft Museum of Art, 4.1931.

Local jewelry expert Kimberly Klosterman has written labels for eight paintings in the Taft’s permanent collection (identified in the Visitor’s Guide) highlighting the jewelry. In Raimundo de Madrazo Garreta’s (1841-1920) portrait of Anna Sinton Taft, who with her husband, Charles, began to assemble the Museum’s collection, she wears a massive pear-shaped natural pearl on a velvet-ribbon choker with a long strand of pearls to complement it. At the beginning of the 20th century, pearls were more highly prized than diamonds. In 1917, Cartier purchased a building on Manhattan’s Fifth Avenue, still the flagship store in the U.S., for a $100 and double-strand of South Sea pearls.

I’d like to add something else to look at in the permanent collection. Hanging above a fireplace in the Renaissance Treasury gallery is an extremely large enamel portrait of François de Clèves, Duke of Nevers, by the Limoges workshop enamelist Léonard Limosin, c. 1506-1575/77. With its elaborate enameled gold frame, it looks like a gigantic brooch.

Don’t think of this exhibition as just a particularly choice jewelry shop. because, as covetable as the pieces are, there’s history to be learned. These “personal sculptures” are artifacts representing the styles and materials favored by a culture. More than mere adornment, they are signifiers of power and wealth; nothing says “king” better than a jewel-encrusted crown.

Before we consider style, the materials used reveal much about a period. For example, after the stock market crashed in 1929, the diminished wealth of even the well heeled made the preferred platinum beyond their reach. Gold became the metal of choice because of its relative affordability, not to mention, it was considered a sounder investment than stocks or bonds.

The 19th century might be seen as a series of revivals as jewelers revisited earlier styles. When Napoléon declared himself emperor in 1804, he sought to legitimize his reign by linking himself to the Roman Empire by reviving classical Greco-Roman styles.

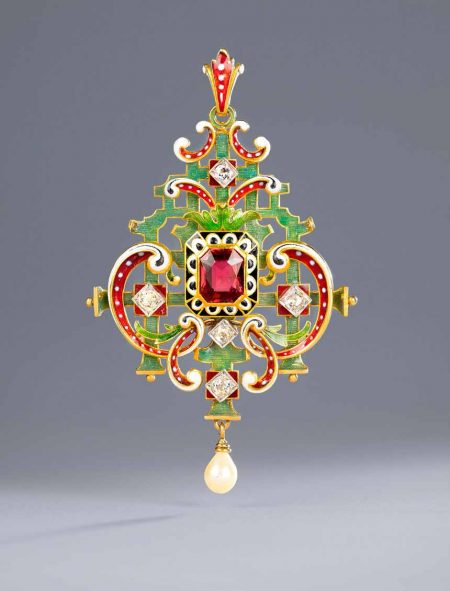

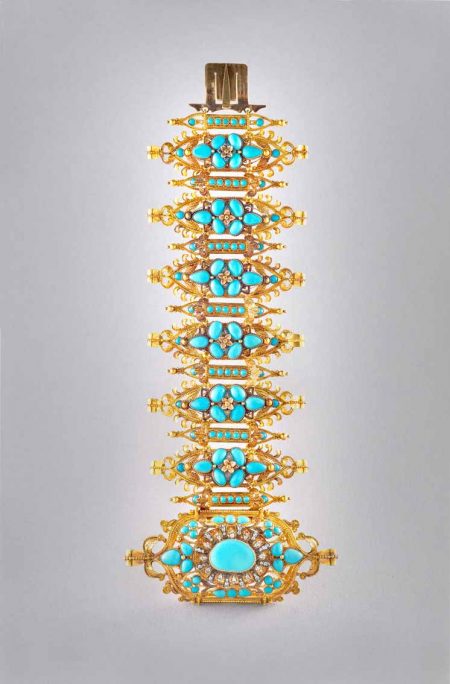

In the second half of the 1800s, the Renaissance also saw a rebirth. Its hallmarks were “symmetry, central stones, scrolls, open arrangements, and hanging elements,” from the Taft’s always informative and accessible labels.

At the end of the 19th century, the light-hearted Rococo “with its playful curves and decorative flourishes” caught the imagination of designers, and floral designs dominated.

Sections of Falize’s Gothic Bracelet echo the spires of a High Gothic cathedral.

At the opposite end of a stylistic spectrum was the Gothic revival. The 1825 opening of the Musée de Cluny had sparked an interest in medieval art. The neo-Gothic style manifested itself most clearly in architecture where it was characterized by ogival arches and soaring heights, construction made possible by the development of flying buttresses. But neo-Gothic was also marked by an obsession with the macabre and the mysterious, horror and death, which was seen in literature in works like Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Bram Stocker’s Dracula, and Edgar Allan Poe’s complete oeuvre.

The exhibition’s Electric Skull Stickpin, c. 1870, is an example of the neo-Gothic. In 1865, the French engineer and inventor Gustave Trouvé (1839-1902) patented a miniature battery that could be used to animate pieces of jewelry. The gentleman wearing this diamond and enamel-over-gold piece could pull on an invisible wire to make the skull’s jaw open and chatter.

Georges Fouquet (1862-1957), design Charles Desrosiers (dates unknown), Sycamore Maple Pendant, about 1905, enamel, gold, diamonds, two peridots, and baroque pearl. Petit Palais, Musée des Beaux-Arts de la Ville de Paris © Patrick Pierrain/Petit Palais/Roger-Viollet. Droits d’auteur © ADAGP.

Moving away from the 19th-century’s dependence on revivals, a completely new style emerged at the turn of the last century–Art Nouveau. Artists looked to nature for inspiration, but abstracted it rather than imitating it. The style was influenced by the asymmetry and fluidity of Japanese art that reached Europe through woodblock prints when the country reopened trade with the West in 1858. The jeweler Alexis Falize (1839-1897) owned more than 50 volumes of Japanese woodcuts.

The Japanese influence is quite obvious in a gold, pearl, and mother-of-pearl Brooch, about 1900, by jeweler and glass artist René Lalique (1860-1945). Engraved on each side of an open oyster shell are tsunami-sized waves rushing toward each other, an obvious homage to woodcuts by Utamaro and Hokusai. The engraving is so faint that studying it while it was being worn would have created an awkward situation.

Art Nouveau artists turned to humble subjects as seen in Debut et Coulon’s Dandelion Brooch, about 1880-1895. A weed was as worthy a subject as any more exotic bloom. Although the piece uses platinum, silver, gold, and diamonds, it also incorporated, definitely not precious swan feathers, which approximated the dandelion’s natural movement.

In Lalique’s horn, silver, and enamel Nasturtium Comb, about 1897-1898, sparkling gems were supplanted by materials that weren’t inherently precious. In Art Nouveau the originality of the design became the standard by which work was judged and valued.

World War I changed everything. The social order of the 19th century was swept away; royal dynasties disappeared; and the status of women changed dramatically. They had entered the workforce in factories and on farms, replacing men who were in the trenches. The independent “New Woman” of the 1920s left the constricting corset behind, shortened her dresses, and bobbed her hair. The new hairstyles led to the development of new head ornaments, including a style of diadem that was a band worn across the forehead.

Art Deco emerged after World War I. Instead of nature, machinery, abstract painting and sculpture, and architecture became the inspiration. Geometric shapes, shiny surfaces, and bright colors replaced the sinuous lines and subtlety of Art Nouveau.

This exhibition shows how jewelry can be much more than a mere bauble, conveying status but also reflecting the cultural zeitgeist. Who knew a history lesson could be so engaging?

–Karen S. Chambers

“Bijoux Parisiens: French Jewelry from the Petit Palais, Paris” (through May 17, 2017), Taft Museum of Art, 316 Pike St., Cincinnati, OH 45202, 513-684-4516, taftmuseum.org. Wed.-Fri. 11 am-4 pm, Sat.-Sun. 11 am-5 pm. Admission: members free; adult $14 in advance, $16 at door; senior (65+)/youth (6-18) $12 in advance, $14 at door; children (5 and younger) free. Sun. $4 in advance, $6 at door; children (5 and younger) free.