BRUCE CONNER: FOREVER AND EVER presents a selection of films and works on paper by the experimental and breakthrough artist Bruce Conner (1933-2008). The exhibition was organized after a recent gift of twenty-one lithographs was presented to the Speed Art Museum by the Conner Family Trust. In conjunction with the exhibition of lithographs, two recent digital restorations of Conner’s 16 mm films, THREE SCREEN RAY (2006) and A MOVIE (1958), is available; both films are on loan from the Conner Family Trust.

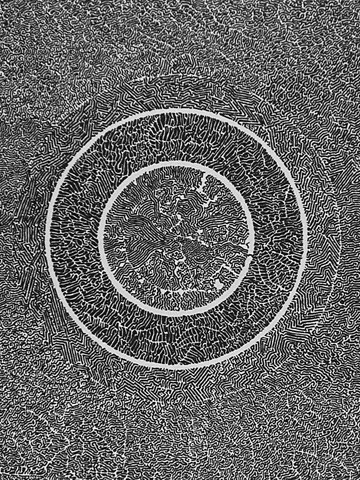

Conner’s work ranged from assemblage or collage sculptures made with materials ranging from, but not limited to, nylon stockings, parts of furniture, broken dolls, fur, costume jewelry, paint, photographs, and candles. He reclaimed objects that had been discarded and neglected (though he largely abandoned assemblage in the early 1960’s). He later turned to mysterious lithographs, referencing mandala designs, photograms of his own body, ink-blot, Rorschach-like drawings and avant-garde films. Conner’s anarchic choice of media possess three commonalities throughout his years: humor, iconoclasm and intransigence. Though Conner’s workhas wide ranging academic respect and desirability now, even having film work preserved in the Library of Congress as an outstanding, and groundbreaking, example of collaged filmmaking, Conner was too anarchic and contrarian a personality to be easily assimilated into the art world.

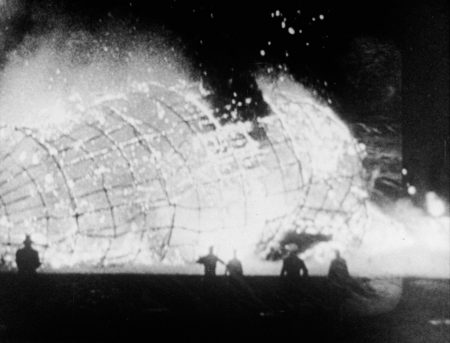

Bruce Conner’s first, and arguably most famous film, A MOVIE (1958) works through three key phases and is presented in a twelve minute loop: First, romantic American and international imagery including but not limited to running horses and cowboys, striking aerial acts such as tight rope walkers, charging elephants, skydivers, softcore pornography, and underwater seascapes. Second is the introduction of a flying Hindenburg, soldiers in uniform, more skydivers, and the introduction of his infamous mushroom cloud footage. And third, images of human destruction: an exploding and crashing Hindenburg, multiple executions, footage of piles of dead soldiers, refugees, amongst others. A MOVIE was the first film made of collaged film stills and one of the first films to leave exposed the film perimeter and time sheets in place. Conner paired A MOVIE with three iterations of Ottorino Respighi’s “Pines of Rome”, utilizing music as a psychological tool in which to manipulate the audience into having specific feelings ranging from nostalgia to disgust. Conner invented the music video thirty years before MTV.

Before music videos and rapid-fire editing pervaded popular culture, Conner pioneered techniques of vertical montage and subliminal messaging with this second film, COSMIC RAY (1961). With thousands of images precisely cut to Ray Charles’ hit song “What’d I Say” (1959), Conner created an explosive homage to the blind musician. More than 40 years later, a derivative work was born from the combination of COSMIC RAY, and silent loop installation EVE-RAY-FOREVER (1965/2006). THREE SCREEN RAY (2006), re-edited and expanded, replaces those two films with three new iterations that share the screen. In collaboration with editor, Michelle Silva, Conner forced images to meet, diverge, and meet again; creating an alogarithm for absurdity. Conner utilizes sexual subtext, war imagery (primarily from World War I) and Micky Mouse to confront consumerism and aggression, while his tour-de-force editing ensures that even after multiple viewings, the viewer will never experience THREE SCREEN RAY the same way twice. It’s impossible, it’s so fast paced and multi visual that it holds the viewer in limbo— never settling into any one spot.

He began working on his lithographs in the 1960’s after a discovery of the newly invented felt tip pen provided him the opportunity to sit for hours creating lines without ever lifting the pen off of the page. For an artist so pulled by an intrinsic self destruction and mania, these lithographs are zen, momentary, studious, and leave powerful afterimages that recall his film style. It’s no wonder that they are often referred to as mandalas— they hold a similar internal power.

The pairing of Bruce Conner’s films with his lithographs gives an unfair impression that he had a controlled disposition and discernible taste— when in fact he had the opposite— a lust for alchemy, destruction, rebirth, and self -cataclysm. I had to wonder if the shared presentation of his assemblage sculptures, Child (1959) for example, would leave the viewer with the same taste in their mouth. Conner definitely had a taste for the horrific and the monstrous— it makes me curious to know what he would think of retrospectives of his work that are in all respects, extremely tasteful. I’m curious what that curatorial decision looked like, since the films were provided on loan alongside the donation of the lithographs. Was a lack of a request for his assemblages a product of minimizing and organizing of an exhibition or a consideration of the conservative arts community that Louisville maintains?

BRUCE CONNER: FOREVER AND EVER will be on view through March 2nd, 2018.

–Megan Bickel