Last semester an English comp student of mine used to stay after class to have further conversations with me. We typically talked about music and capitalism as his work was intensely focused on hip-hop and social justice. His final paper was about the work of a New York based Haitian rapper named Mach Hommy. Mach Hommy’s work tends to fuse English rhymes with Haitian Creole, bringing Haitian culture to bear on his lived experiences as a black New Yorker. The student and I spent a lot of time attempting to figure out Mach Hommy’s sales techniques. His records are not widely available digitally, but physical pressings are ultra limited, ranging in price from around 70 dollars up to over 2000 dollars. We consistently asked “why?”

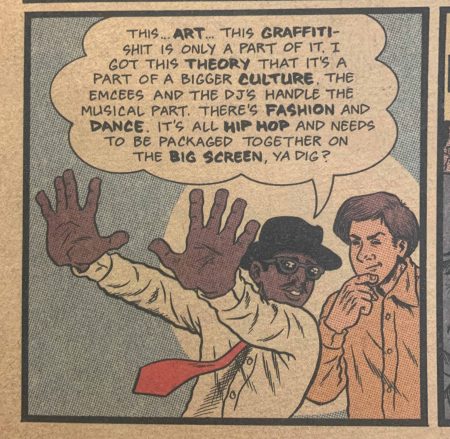

Oddly, my student wasn’t yet familiar with the work of Jean Michel Basquiat (of partially Haitian descent)– an artist whom I’d posit Mach Hommy to be a direct descendant of. My first encounter with Basquiat was within direct context of hip-hop culture. In high school I read a comic by graphic artist Ed Piskor called “Hip Hop Family Tree,” a series in which Piskor attempted to trace a graphic history of hip-hop beginning in the 70s (I recommend it as a useful primer for interested readers). Piskor’s depiction follows common biographical understandings of Basquiat as a key figure in the New York downtown underground art scene in the late 70s and 80s as well as the punk rock, Avant-garde and hip-hop scenes that were often woven together. One particular panel focuses on the vision of filmmaker Charlie Ahearn. His 1982 film Wild Style features work by Basquiat, Keith Haring and Fab Five Freddy as evidence of visual and street art as a subset of hip-hop culture. It’s a vision that characterizes hip-hop as a movement that draws heavily on social dissent and independent creation as well as blending of influences (i.e. the cutting and mixing of old records to makes new beats and tracks). Punk and Avant-garde shared many of these characteristics, though hip-hop differentiated by being primarily birthed from black culture. I reflect on all of this because I think it’s important in characterizing Basquiat as a pioneering figure of independent, black art which still speaks to our time hauntingly while continuously engaging in complex relations with institutions like the art world and wider forms of commodification.

I began with Mach Hommy because he’s a contemporary example of tensions between black art and commercialism. He exists in a time in which it’s rather easy to find music. Even if his records don’t exist on popular outlets like Spotify or Apple Music, they can be found in different crevices of the Internet. To sell records at his prices is to recognize that the commercialism and popular culture always, inevitably harness art – in this case black art – in unpredictable ways. Despite working in a genre that was born in the streets, he recognizes that hip-hop now (in contrast to what it was in Basquiat’s time) is a driving force of popular culture. His prices assure us that his music is not pop music and that his music is, in fact, art. Basquiat’s approach wasn’t exactly the same (nor, obviously, was his context), but his ideas and his work exist in a similar paradigm. He was literally an artist of the streets, beginning his public career as a part of the graffiti duo SAMO. Those works of language and raw images painted on walls and trains remains a consistent thread. One overwhelming duality in his work as an artist is that even when he was an artist of galleries and installations, he also – like Keith Haring and Fab Five Freddy – remained an artist of the streets. People didn’t – and I suspect still don’t – quite know what to do with that duality.

Criticism from the time alludes that his blackness was likely a factor fueling some confused responses to his work, and he was very much aware of this. One interviewer asked him if he’d agree that his work could be considered “Primitive Expressionism,” and he responds with a wry smirk asking “like an ape?” The interviewer clearly feels discomfort at that analysis of what he may not have realized was racist language. In Tamra Davis’ documentary on The Radiant Child (which is a useful introduction to the artist and is available to stream with an Amazon Prime account) Peter Brant says, “He was not an artist that was praised by the art world cognoscenti. He was considered an artist who could be on the cover of the New York Times Magazine section because there was a lot of underground feel to the work.” His fame in and contrary to the art world in the 80s was complex – clearly his usage of graffiti and street styles perplexed the art world. His fame now continually holds that complexity for different reasons. On one hand, in 2017 one of his paintings sold for 111 million dollars – the sixth highest price ever paid for a painting at that time. On the other hand, his images are widely commercialized. Below is an image of a t-shirt that can be purchased on Amazon for $22.99. Basquiat’s crown, in particular, is all over the place (in fact, one reason I selected Basquiat for this piece was because I had seen a striking number of both white and black people wearing apparel with the crown at various recent Black Lives Matter protests). I’m not entirely sure what to make of this hyper canonization of someone who essentially sprouted from underground, Avant-garde and street subcultures. My fear is that to popularize and canonize counter-culture inevitably diminishes the value and perceptions of the work. This fear is one reason why I think it’s important to continue diligently reading and writing about the complexities of artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat.

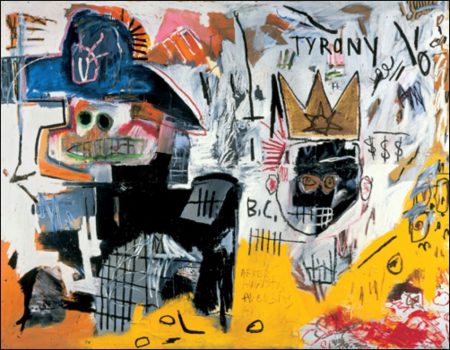

Bodies and words are two primary components of Basquiat’s work. Like many before me I find much of his work perplexing and some of his purposes obscure. Years ago I purchased a small print of a 1982 piece called “Dustheads” and it’s been on my wall ever since. I look at it everyday yet I’ve never fully come up with an interpretation of it. Perhaps that’s one reason it caught my eye. Like much of his work the colors of “Dustheads” are vivid – in this particular piece warm colors take precedence with just enough cool colors to maintain balance. “Dustheads” is also exemplary of the energies present in his work. Like much of the hip-hop – especially from the 80s – Basquiat’s work is filled with kinetic energy. The looseness of the lines and scrawled words give an appearance of a gleeful playfulness. Basquiat always painted with a record on, and that music is imbued in the work. There is also a menace to the works as if he’s aware of the darkness beneath what he’s painting. In “Dustheads,” the figure on the left could be in danger of attack by what might be an uncontrollable, sporadic figure on the right. They could just as easily be a child playfully sneaking up on his father or friend. Hip-hop music plays with dance and energy yet, as a genre, has always been deftly aware of human unpredictability – especially in regard to law enforcement and power structures. I think Basquiat was very much aware of, and channeling, the same dualities.

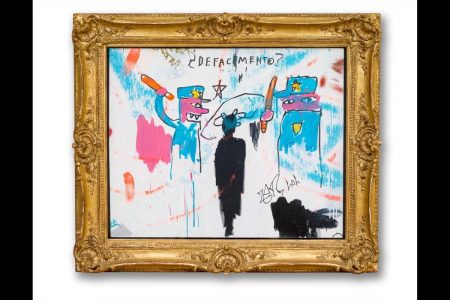

In 1983 Basquiat painted a rather explicit political piece called “Defacement” in response to the death of his friend Michael Stewart – a graffiti artist – at the hands of the police. In this era of the Black Lives Matter movement, “Defacement” unfortunately remains a calling card for American Law enforcement. The colors here seem simple. The light blues and reds of police and blood spackle the background, while Stewart’s diminished black body comprises the middle. Like “Dustheads,” it’s a jarring image. On the surface, the colors aren’t particularly threatening; the tone of the painting might not strike one as immediately violent. Of course, the intention of the content is obvious. The police menace over Stewart’s dwindling figure. Their faces are monstrous, the arms raising clubs high in order to be brought down with great force. They look like villains having a field day, lucky to complete today’s task. The bright colors of the figures and their backdrop suggest that the violence is injected with some playfulness – these officers wanted their violence. The backdrop might also allude to the normalcy of the scene that Basquiat paints here. The colors make a grotesque scene uncomfortably easy on the eyes. If his intention was to diagnose this violence as normalcy, it should be clear forty years later that he was correct. Above the scene, the written word “defacement” looms. It suggests that the police are punishing Stewart for the defacement of public surfaces. It suggests that black bodies are worth less than these public surfaces. It suggests the defacement of black bodies by law enforcement and the defacement of Michael Stewart himself. The question marks that bookend the word serve to throw any simple meaning out of whack, pushing us to pose the obvious questions and criticisms of police violence, as we still are right now. The people complaining about looting today are the same people who would complain about Stewart’s graffiti then.

One last piece that I think characterizes Basquiat as a painter, as a hip-hop artist and as an Avant-garde punk is an untitled piece labeled “Tyrany” (note the spelling in the painting). This is a specific example of a depiction of his crown that looms in my brain when I see the t-shirts in the streets, and it’s an example of what I think makes his work so valuable. The crown is typically seen as celebratory. He used it to celebrate “black kings” like Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Sugar Ray Robinson. Indeed, I think it’s powerful in that context – it’s commercially printed for obvious reasons. “Tyrany,” however, seems to tell a different story. The figure on the left appears to be a pirate or captain, while the figure on the right seems to be a king ordering his servant to bring him fame and riches. The dollar signs and the word “tyrany” seem to point obviously toward the greed and flaws of the king. This king contrasts the kings whom the artist celebrates. It’s an image that tells us that for Basquiat “black king” was not an exclusively positive term. In context with “Defacement,” it’s another acknowledgement of corruption of power. The image, which I’ve reflected on as a t-shirt symbol, actually holds more nuance than wearers may realize. The crown is a fascinating icon in the artist’s work because it’s a multilayered symbol. Like hip-hop, he uses it to blend together and celebrate his influences and icons. Like hip-hop, punk rock and the Avant-garde, it’s a symbol of skepticism and dissent. It’s an image of an artist who was of the streets and the art world, while also being neither – an artist of celebration and dissent. My fears about mass production and hyper canonization are not necessarily about any kind of devalued authenticity of the work, but rather of laziness on the part of admirers and audiences. Since Basquiat died at 27 of a heroin overdose, it’s been commonly suggested that his fame and critical misunderstandings were primary culprits. He – like his good friend Andy Warhol – wanted to be famous, but didn’t really know how to handle it when he got it. This is not to suggest that it’s wrong to wear a crown shirt, but that we might have more respect for the symbols and cultures that we take up.

–Josh Becklehimer