By: Maria Seda-Reeder

“Found in Translation: Work by Cynthia Gregory, Christian Schmit and Greg Swiger” at Semantics Gallery is the kind of show at which you can get lost. The mostly miniature/sculptural works are tiny assemblages of objects that range from meticulously crafted to purposefully undone. Diminutive paintings, drawings, furniture, and found objects round out a densely packed gallery of seventy-three discreet pieces—more if you count the few that occupy the hallway between the front and back galleries but are not listed on the Works Title sheet.

“Found” is ostensibly a “collaborative effort”—of which, five are actually co-authored. Gregory says on her website that the show is the result of a call and response system between the three neighbors who left prompts on each other’s doorsteps; and the gallery is chockfull of fanciful vignettes on shelves installed along the walls around every turn.

Gregory crafts miniature recreations of banal yet sentimental objects (star charts, feathers, rocks, and books), but her work tends to be more two-dimensional, with the significant exception of her Poet’s Table—one of the few life-sized objects within “Found.” The current graduate of DAAP’s MFA program has the most pieces in the show (thirty-nine compared to Schmit’s twenty-five and Swiger’s thirteen), lending “Found” an overall visual unity but it also seems crowded.

In American Heritage, World Book, two “books” rest on the floor against a window ledge and behind them is another mini fragment of an idea (matchbook tray with stamps and what appears to be a bingo chip inside), and the entire exhibition is chockfull of these. While I enjoy the experience of discovery to which Gregory seems committed, and her quality of craftsmanship is painstaking, the work would do well to have more breathing room.

Swiger is also a recent DAAP MFA grad but his work is quite different: less intent on craft than either Gregory or Schmit, Swiger’s work is easy to identify throughout “Found.” Like the other two, he is equally interested in assemblages, but Swiger’s work is more colorful and disordered. Although Swiger’s creative voice is recognizable, his work benefits from being paired with the other two.

For example, in Orange Box, Plant Table, Swiger & Schmit demonstrate their aforementioned call and response method: upon one shelf, Schmit’s doll-sized table supports a potted miniature snake plant and, atop a corresponding shelf (just inches to the left and nearly out of viewable height), rests Swiger’s folded orange box held together by binder clip and a drawing of Schmit’s plant taped to the wall above it. To join the two together, a green piece of string connects the shelves via their respective plants. When taken together, Schmit’s simple model of a familiar object and Swiger’s conceptually based box and drawing have further resonance than they would if taken alone.

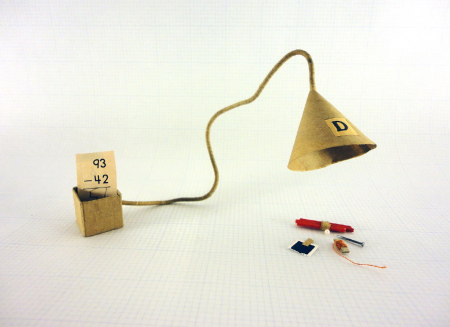

Schmit’s work is so sculpturally tinged that even his miniature painting The Teignmouth Electron contains three-dimensional elements (an attached overhead light that shines upon the maritime painting), and the frame/light component seems just as significant as the image itself. The artist’s work is particularly more whimsical than his neighbors’ with pieces such as the doll-sized RocketMan’s Work Clothes (a hand sewn blue jumpsuit hung from a custom-made hanger upon a peg shelf, on top of which rests a wee red stocking cap) look like they were made for a Muppet or some other fantastical creature.

According to the exhibition bio for Schmit, for the last several years his work has been dedicated to a large-scale installation piece entitled “A Memory Rocket” depicting a last man on earth character. The artist extracted his “sculptural manifestations of thoughts and memories” from the aforementioned Rocket, in order to work them into more stand-alone pieces for “Found,” but they retain their imaginative quality.

The small shelves used for exhibiting these precious, multi-piece groupings are a unifying technique throughout and parallel Schmit’s & (to a lesser extent) Gregory’s interest in placing objects upon some kind of pedestal. Tables abound within the exhibition and many pieces involve multiple bases: boxes are stacked, books are piled, and smaller tables rest upon larger ones, placed upon shelving. While this technique makes for attention-provoking work, the exhibition can seem visibly chaotic without the space to process it all.

The works are installed at varying heights along the walls (some so far above it is nearly impossible to see), propped on the floor, along windowsills & mantels—demonstrating a keen interest in capturing viewers’ attentions. Many pieces are hidden just out of sight, (as in Swiger’s Seahorse or Gregory’s aforementioned American Heritage, World Book), only visible from behind via a mirror (a la Gregory’s Mantlings), or implicative of visibility (as Schmit does with his moving Blue Box with its opening and closing mechanism.)

There is so much to see in “Found” and it is filled with sparkling moments of discovery, but its strength is also its weakness: there can be too much of a good thing. Because there are so many pieces in the show and each artist is committed to the idea of assemblage, the work loses some of its preciousness, which, taken alone, might have a stronger impact. The sheer number and resultant visual chaos feels overwhelming at points, but if viewers allow themselves to get lost in the details the content of “Found” is treasurable.

“Found In Translation Work by Cynthia Gregory, Christian Schmit and Greg Swiger” runs through Saturday, July 28 at Semantics Gallery