A slow-burning ambiguity inhabits the title of Anthony Luensman’s New Works, which now hang at the Clay Street Press Gallery in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine district. Most plainly, the pieces are new in the sense of making their first public appearance, of being still fresh in an era when things age at breakneck pace. The offspring of Luensman’s relocation from Cincinnati to Tucson, they represent a departure from the multi-tiered installations, neon sculpture, avant-garde music, experimental theater, and comic-erotic photography that have marked his previous Ohio shows. But the exhibition also destabilizes the idea of “new works” by making use of traditional materials while revisiting subjects that have occupied the artist’s mind for decades. Luensman captures the paradox not only in the form of the paintings but the language that attends their production: citing Louis de Bernière, he explains that “I find new ways to be an anachronism” (Anthony). Wrangling with time, the artist never settles comfortably into the dominant currents of his moment. Given the raw materials of the show—primer, chalk, masking tape, staples, rubber, milk paint—we might modify the de Bernière quotation and suggest that Luensman finds old ways to address emergent problems. Those problems have a long lineage, the images imply, but we are still learning how to frame them.

For Luensman, framing them with timeworn media follows a surfeit of success with formal innovation. After winning a National Endowment for the Arts Award and an Efroymson Contemporary Arts Fellowship, and after authoring exhibitions in such places as Louisville, Detroit, and Taipei, he set aside the engineering of grand-scale projects in 2016 and left for the desert. “After twenty-five years of working with large sculpture, technology, and installation,” he writes,

I began to grow weary of the complicated processes that kept me out of my studio in a constant sourcing of materials and services and on-site installations. I was also ready to disappear for a while from an art scene that I was finding to be overly thematic and too cleverly curated. (Wherevent)

The hiatus permitted him to spend less time managing and more time realizing the conceptual potential of the small, wondrous accidents that attend his composing process. Those accidents coalesce as a visualization of the psyche and the cosmos, an attunement to the harmonies of inner space and outer space. In keeping with his critique of a predictable and restrictive “art scene,” those accidents also yield a subversive look at the commodity form, challenging the product fetish that pursues lost plenitude while finding only dissipation and decay. Each accident presents a puzzle for Luensman that may be formal, sociopolitical, or both. The drive toward a solution impels the production process, though the artist refuses to display his answers in showy or didactic ways (Fox). Both the enigma and the key tend to hide, making the experience of the works a demanding and surprising affair.

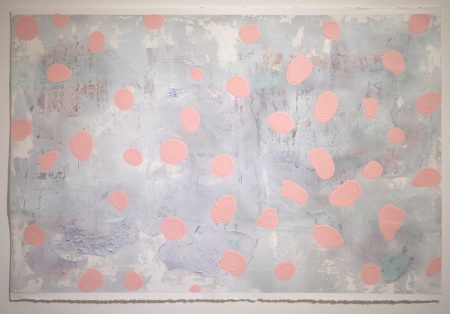

One surprise comes from how he merges the astronomical and the psychological, rendering stars and moon and milky splashes as figures for consciousness. In “pebblestars,” for instance, his humorous evocation of the night sky coexists with allusions to repression and things bubbling to awareness. Several paintings in the exhibit unfold in layers, their texture and style changing starkly as the eye travels along vertical or horizontal paths. But with “pebblestars” the layers press forward into the visual plane, indicating background structures whose outlines are visible but whose details remain murky. Blobs of thick coherence float on the surface, but their exteriors have started to crack. They swim in a mist that masks more imposing forms, some barely suggesting themselves and others beginning to penetrate the gluey glaze. For all Luensman’s deliberation in shifting from kinetic installations to wall hangings, the new works convey a strong impression of movement. And in a sense they do move, mutating with time as imperceptibly as a changing mind, already disclosing fissures in the skin of the milk paint.

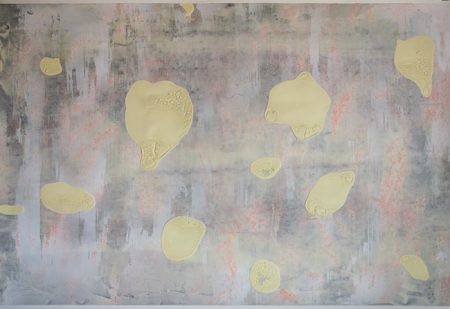

The poetics of becoming and erosion also inform “rubbermoons” and “milkspill,” where the splotches are larger and less numerous than in “pebblestars.” In “milkspill” they expand and drip, connoting the fluids of arousal and release. The new works thus carry forward the whimsical erotics of his 2012 show Taint, in which towers of ringed light mimicked ejaculation, and a ceiling-high totem pole relied on translucent dildos as its core components. Among the more striking pieces stood “ASFALLSBUKKAKESOFALLSBUKKAKEFALLS,” in which the artist spliced video stills “into thirty-second loops of varying speeds. The images show close-ups of handsome young men while a white-gloved hand (Luensman’s) playfully caresses their faces” (Ramos). Such bawdy vernacular reappears in “milkspill,” where the runny film behind the amoebas evokes the smear and spatter of public bathroom stalls, the residues of the illicit and the carnal. Constellations of rust hover in the atmosphere, reminding us of Luensman’s concern with heavenly bodies as much as human ones, his intermingling of the two in ways that are by turns tongue-in-cheek and fully earnest.

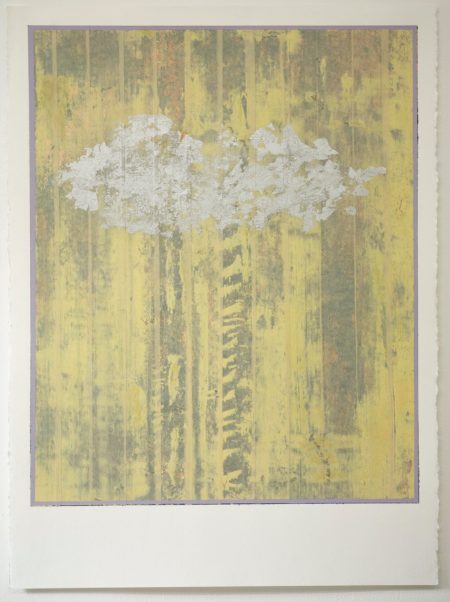

The attention to celestial things continues in his “Polaroid” paintings, which imitate the form of the quick-developing, low-resolution photograph while often emphasizing the vertical striations that flow through Polaroid lenses. “stardrain” inverts visual norms by whitening the evening firmament and turning the stars black. Much of the image is a blur, which affords the inky sky-drain definition by contrast. Drifts of autumnal color and undulating belts pull toward the cluster of holes, which appears to sit atop the painting’s outer plane while paradoxically constituting its deepest location. Like “pebblestars,” it demonstrates the motility of seemingly steady forms, sucking the surface of the image into its vortex.

Other polaroid paintings signal motion through agitated striping, connoting rainfall or the action of blinds, lending us various views through the pane depending on our angle of approach and how the oil catches the light. In some instances the effect recalls television snow, in others the stretching of crumpled paper or the folds of a silken fan. Pigment streams through the bands like graffiti spray. The “masked cloud #1” polaroid generates a certain irony given the cloud’s lucid prominence, especially amid works that mostly decline mimesis. But the title is nonetheless apt, indexing the tape Luensman uses to subdivide the image and designating the cloud’s tenuous assumption of form through a mustard haze. The idea of something masked yet intelligible captures the developing polaroid, transitioning before our eyes from vagueness to figure. Ropey trunks and smokestacks feed upward through that figure, along with more distant structures that defy linkage to readily nameable things.

Such resistance to categorization exemplifies Luensman’s subtle antagonism toward commodity culture, as his accentuation of composing processes, metamorphosis, and the dialectic of emergence and decay all point to dissatisfaction with market-friendly fixity. This oppositional ethos recalls his earlier “novembermood,” for example, where high-density striping resembles a disintegrating barcode. The perspective here echoes that of Walter Benjamin in The Arcades Project and “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” which describe the fascination with commercial goods and their consummatory promise, only to follow the description with portraits of wreckage. In 2016, Luensman developed that line of argument in a numbered series of “… _ _ _ …” paintings that refused even the stability of a title. They look like Mark Rothko pieces left out in the weather, drenched in bodily fluids, electrified, and in one instance, attacked by Jackson Pollock in his black pourings phase. But even as the allusions to modernist forebears begin to accrue, Luensman addresses his problems in distinctive ways, fashioning anti-merchandise amid weird galaxies that are unquestionably his own.

The anticapitalist dimensions of the new works have precedent in earlier projects like Self-Reliance and “C A M P G R O U N D,” the latter of which featured a neon road-sign containing a swaying, incandescent tire-swing and flickering bonfire. The piece converted stripped-down, idyllic pleasures into kitsch, questioning both the nostalgia for supposedly simpler times and the seductions of luminous repackaging. But however scathing Luensman’s compositions might appear in an era of xenophobic branding, he avoids pedantry in favor of inquiry, proceeding in an invented language whose grammar he composes as he goes. At times that language conveys percolation and explosion, at others entropy or burnout. It depicts the interstellar and the infinitesimal at nearly the same moment: shapes that fill the sky might also wriggle beneath a microscope. And the novelty of those structures emerges from self-conscious encounters with classic media, the formulation of wicked problems whose solution can never be singular, and never the artist’s alone. Those problems include the visualization of affect, the nature of agency in the face of the corporate “art scene,” the alienation of performer from performance. Answers to those problems prove untimely, out-of-joint, never coming quickly or powerfully enough to allay their founding anxiety. Such anachronism may explain the new works’ preoccupation with stars, whose beams must travel great distances to reach us, and whose arrival comes always too late, an elegy for their own making.

—Christopher Carter

Works Cited

Anthony Luensman.com. www.anthonyluensman.com/about.html. Accessed 17 Sep. 2017.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project. Trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin. Belknap Press, 1999.

—. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Trans. Harry Zohn. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1968.

Fox, Charles. “Outposts from the Material World.” outpostsfromthematerialworld. blogspot.com/2009/11/conversations-with-tony-luensman.html. Accessed 17 Sep. 2017.

Ramos, Steve. “Secret Dildo Sculptures and Abstract Neon Erotica.” hyperallergic.com/59170/anthony-luensman-taint/. Accessed 17 Sep. 2017.

Wherevent.com. “Anthony Luensman: New Works.” www.wherevent.com/detail/ Clay-Street-Press-Anthony-Luensman-New-Works. Accessed 17 Sep. 2017.

Christopher,

Excellent insightful review of the work. The abstract is never as obtuse as it seems.

Christopher,

Excellent insightful review of the work. The abstract is never as obtuse as it seems.