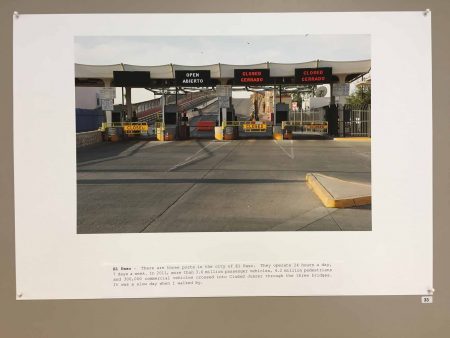

“There are three ports in the city of El Paso. They operate 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. In 2011, more that 3.6 million passenger vehicles, 4.2 million pedestrians, and 300,000 commercial vehicles crossed into Ciudad Juárez through the three bridges. It was a slow day when I walked by.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

Bear with me a moment. I want to explain the impetus for the “Crossing the Border” series by Jens Rosenkrantz, Jr., which is currently on view at the Clifton Cultural Arts Center. This is stuff we all (I assume) know, but may forget as the controversy surrounding President Donald J. Trump’s call for a wall to protect the border between the U.S. and Mexico evolves. The border stretches 1,954 miles from the Gulf of Mexico near Brownsville, TX, to the Pacific Ocean near San Diego.1 According to a 2016 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office, 650 miles of the border already have vehicle and pedestrian fencing.2

At those raucous Trump campaign rallies, the chant reverberating was “Build the wall.” When the candidate asked, “Who will pay for the wall?” his adoring audiences called back, “Mexico will pay for the wall.”

But right now the Trump administration is looking for money from Congress to construct a wall whose efficacy is debatable. Evidently he expects Mexico to reimburse the American taxpayer.

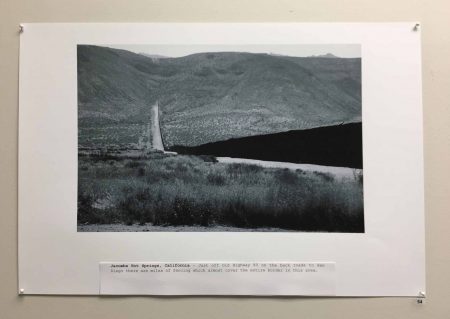

“Just off Old Highway 80 on the back roads to San Diego, there are miles of fencing, which almost cover the entire border in this area.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

Despite the frenzy whipped up by Trump at his rallies, there is opposition, and it’s not only from his political foes. In the wall text Rosenkrantz notes, “The slogans have played well in the Midwest, but along the border, especially in Texas, which would bear the largest impact of the wall (1,200 miles), many there seem to be more focused on the realities of such a project as it is their land and their jobs and their neighbors.”

Because much of the land where the wall will be built is in private hands, it will have to be acquired through eminent domain. This is riling up resentment against the intrusion of the federal government in local affairs and promises years of litigation as the locals fight Washington.

This situation inspired Rosenkrantz to undertake a 12-day journey to record what the border looks like today. He started on May 20, 2017, when he landed in Houston, and traveled 3,000 miles, taking 2,000 photos, around 60 of which are displayed in “Crossing the Border.”

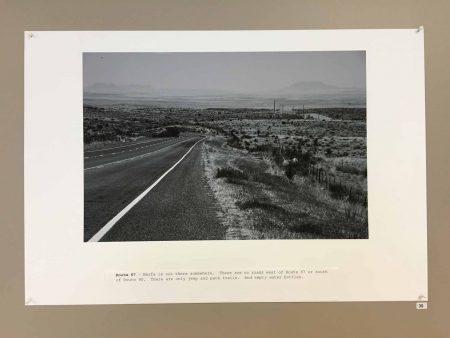

“Marfa is out there somewhere. There are no roads west of 67 or south of Route 90. There are only jeep and pack trails. And empty water bottles.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

Rosenkrantz shoots in both black-and-white and color, a choice he makes for each digital photo, guided by aesthetics not the subject matter. He imparts a yellow haze to his color work, and the black-and-white photos are never stark but hint at a subtle toning.

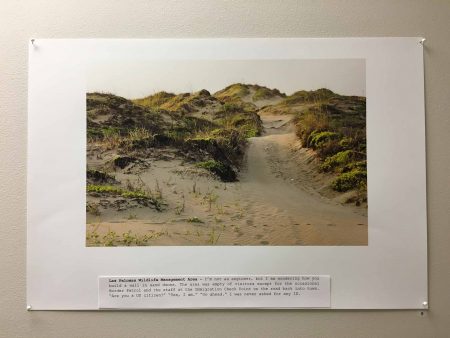

“I’m not an engineer, but I am wondering how you build a wall in sand dunes. The area was empty of visitors except for the occasional Border Patrol and the staff at the Immigration Check Point on the road back into town. ‘Are you a U.S. citizen?’ ‘Yes, I am.’ ‘Go ahead.’ I was never asked for any ID.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

On his travels Rosenkrantz encountered some areas that already have barriers (walls and fences) and some of the 48 official crossings. He also photographed the open land where the wall will be built, if engineers can conquer nature. For example, Rosenkrantz questions how they will tackle the dunes of the Las Palomas Wildlife Management Area in Texas.

“I look forward to seeing the new prototypes of the ‘Wall’ as there will be solid concrete examples and others will be of ‘other materials,’ which will allow a transparent view to the other side. I’m not sure if solar panels will be included in the prototypes.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

In documenting the barriers already in place, Rosenkrantz often used them as graphic elements in his well-considered compositions. The border at Jacumba Hot Springs is guarded by what I take to be iron beams, spaced slightly apart to thwart anyone who dares breech the line between the U.S. and its southern neighbor. They could be likened to a regimented line of menhirs but also prison bars.

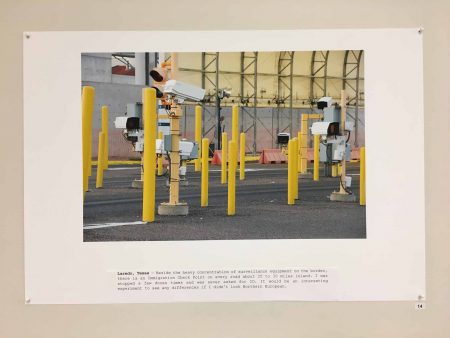

“Besides the heavy concentration of surveillance equipment on the border, there is an Immigration Check Point on every road about 20 to 30 miles inland, I was stopped a few dozen times and was never asked for ID. It would be an interesting experiment to see any differences if I didn’t look Northern European.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

Rosenkrantz also photographed some of the legal entry points. There were 163.3 million people who crossed into the U.S. from Mexico in personal vehicles or as pedestrians in 2013.3

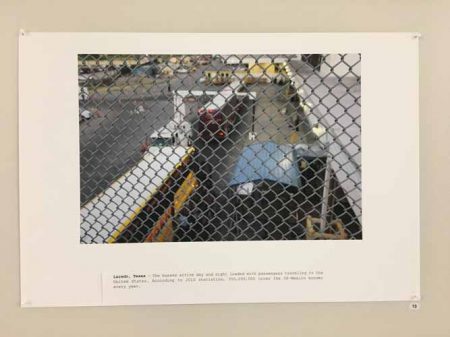

“The busses (sic) arrive day and night loaded with passengers traveling to the United States. According to 2010 statistics, 350,000 cross the U.S.-Mexican border every year.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

In another Laredo photo, he shoots from behind a chain link fence, which acts like a screen overlaid on the scene. What you see beyond the fence are buses making the crossing.

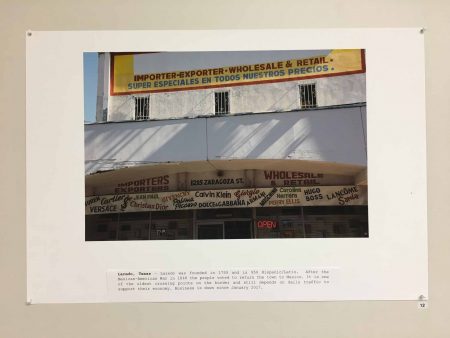

“Laredo was founded in 1755 and 95% Hispanic/Latin. After the Mexican-America War in 1848 the people voted to return the town to Mexico. It is one of the oldest crossing points on the border and still depends on daily traffic to support their economy. Business is down since January 2017.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

But Trump’s crackdown on illegal immigration has also discouraged legal border crossings, which are on track to be the fewest since 2001. This has affected local business by as much as 20%, according to Rosenkrantz.

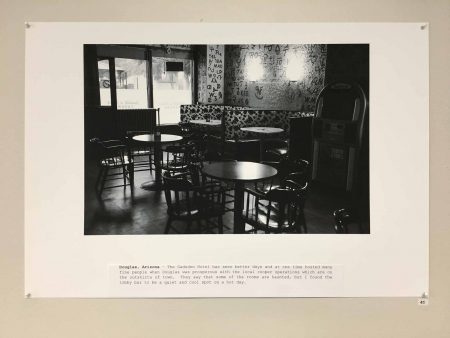

“The Gadsen Hotel has seen better days and at one time hosted many fine people when Douglas was prosperous with the local copper operations, which are on the outskirts of town. They say that some of the rooms are haunted, but I found the lobby bar to be a quiet and cool spot on a hot day.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

I find Rosenkrantz’s empty interiors and exterior views of stores with no customers in sight the most affecting images. Shot in black-and-white, the lobby bar at the Gadsen Hotel in Douglas, AZ, is haunting. Although it’s empty, the human presence is implied by the captain’s chairs carefully placed to surround the round tables. And someone has polished their tops, which reflect patches of sunlight. Rosenkrantz notes that the hotel “has seen better days” when copper mining attracted “many fine people.”

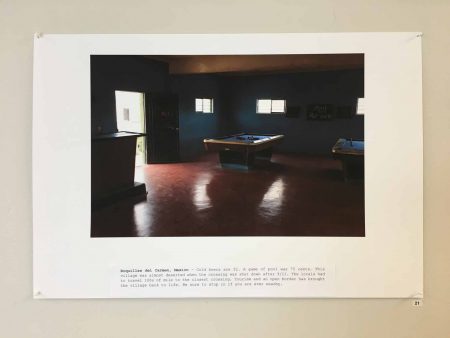

“Cold beers are $2. A game of pool was 75 cents. This village was almost deserted when the crossing was shut down after 9/11. The locals had to travel 100s of miles to the closest crossing. Tourism and an open border has brought the village back to life. Be sure to stop in if you are ever nearby.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

For another deserted bar, this time in Boquillas del Carmen, Mexico, Rosenkrantz uses color. The central pool table, one of two, is nearly bracketed by two parentheses-shaped pools of sunlight on the red clay floor.

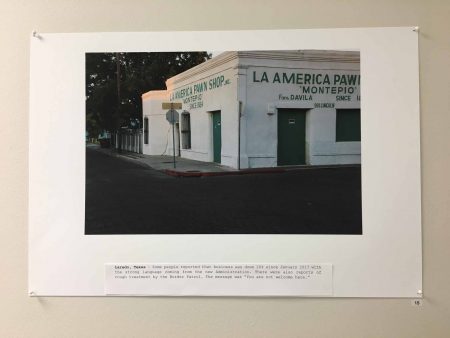

“Some people reported that business was down 20% since January 2017 with the strong language coming from the new Administration. There were also reports of rough treatment by the Border Patrol. The message was ‘You are not welcome here.’” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

The stuccoed La America Pawn Shop in Laredo sits on what might be expected to be a busy street corner, but the streets and sidewalk are empty. The shop appears to be closed, perhaps a victim of the downturn in business that coincided with Trump’s inauguration in January.

Rosenkrantz’s photos address the controversy over the wall, but—let me go far out on a limb here–they are no more dogmatic or propagandistic than Walker Evans’ work for the Farm Security Administration during the Depression. Of course, Evans was tasked with documenting the rural poor to make the point that poverty was no respecter of city limits, but the results transcended that intention. Rosenkrantz has a personal desire to bring attention to what’s afoot politically today, but his images can stand on their own.

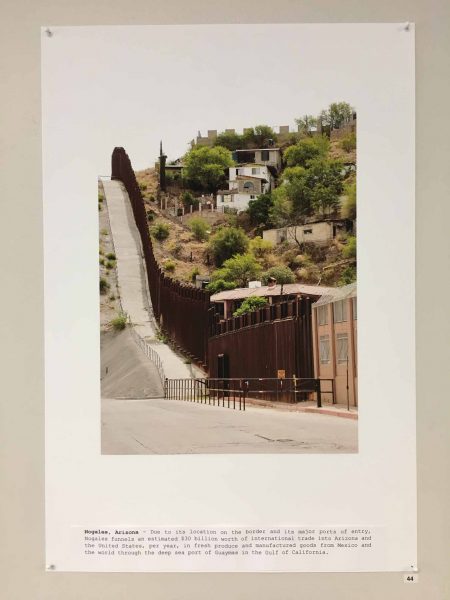

“Due to its location on the border and its major ports of entry, Nogales funnels an estimated $30 billion worth of international trade into Arizona and the United States, per year, in fresh produce and manufactured goods from Mexico and the world through the deep sea port of Guaymas in the Gulf of California.” Jens Rosenkrantz (Photo courtesy of Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Cincinnati, OH)

–Karen S. Chambers

END NOTES

1 “The total length of the continental border is 3,201 kilometers (1,989 miles). From the Gulf of Mexico, it follows the course of the Rio Grande (Río Bravo del Norte) to the border crossing at Ciudad Juárez, Chihuahua, and El Paso, Texas. Westward from El Paso–Juárez, it crosses vast tracts of the Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts to the Colorado River Delta and San Diego–Tijuana, before reaching the Pacific Ocean. Wikipedia.

2 Cristina Silva, “Donald Trump Border Wall: Who Will Pay For It, What Will It Look Like And How Much Will It Cost,” International Business Times, November 8, 2016.

3 Wikipedia, op. cit.

“Crossing the Border,” Clifton Cultural Arts Center, 3711 Clifton Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45220. www.cliftonculturalartscenter.org. Mon.-Thurs., 10 a.m.–7 p.m.; Sat., 9 a.m.-noon. Through Nov. 3, 2017.