A “drive-thru” restaurant. Aging wood-frame houses. Desolate T-docks. In her latest show at Linda Hodges Gallery in Seattle’s Pioneer Square neighborhood, Daphne Minkoff portrays forgotten pockets of the urban landscape through collage and oil paints. No figures populate these ordinary spaces, yet the signs of human activity remain, in the graffiti and old advertisements that still adorn the walls, and in the very scuffs and imperfections of the buildings. By revisiting corners of mundanity with fresh eyes, Minkoff invites viewers to puzzle over the lost histories of places usually ignored.

In another part of the gallery, artist Tim Cross likewise presents evocative cityscapes and environments noticeably devoid of people. However, his artworks—pigment transfers on massive panels of diaphanous silk—look not to the past but to an imagined future. Composing surreal gardens and dreamlike architectures from repurposed magazine clippings and photocopies of his own sketches, Cross depicts settings inspired by science fiction, at once familiar and alien.

The works in these powerful exhibitions, on display at Linda Hodges Gallery through Jan. 30, 2016, suggest narratives behind each and every structure, from Minkoff’s abandoned shopfronts to Cross’s space-age towers. Yet, upon closer observation, these artworks hide another type of story: that of their very composition.

Minkoff affixes reproductions of her own photographs to board and adds thick layers of oil paint. Then, she reverses her process, scratching away at her pieces to reveal parts of the covered images, sometimes even gouging holes in the paper beneath. “I want the way in which the materials are applied, scraped, and torn away to be a reflection of the subject matter—like an archeological artifact that has many layers of history and memories,” Minkoff explains. This technique of building up and tearing down deliberately mirrors the fate of the structures that she portrays.

Many of these time-worn buildings lie in Seattle’s rapidly gentrifying Central District, and over time some of Minkoff’s subjects have been demolished. Her work implicitly tells the story not only of specific houses or spaces; as a body, her art chronicles the transformation of the local urban environment.

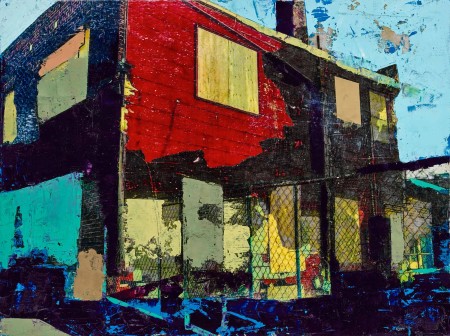

Like Robert Adams, William Christenberry, William Eggleston, and Aaron Siskind (all photographers she names as influences), Daphne Minkoff captures the vestiges of a vanishing way of life. Her artist’s gaze lingers on the details of urban decay and neglect, for example, missing letters in the signage over an old hardware store, boarded-up windows, or the graffiti-buried posters for past events shown in her work, “Blue Light.” Minkoff elaborates, “The idea was to take notice of things that I may have driven by hundreds of times before—pay attention to what is in my peripheral vision. Sometimes it was a flash of color or a melancholy feeling the building had, or the play of light and shadow.”

Her artworks convey nostalgia and loss but also surprising beauty in color, shape, and lighting. Minkoff highlights the angles of buildings with bold blocks of color—yellow, turquoise, red—reminiscent of the work of Seattle-based painter Michael Howard. Minkoff’s emphasis on geometry and line recalls the painting of Hans Hofmann and Richard Diebenkorn, who also inspired her. The stark contrast between areas of color and expanses of black in Minkoff’s compositions creates the illusion of bright sunlight, anchoring her images to a distinct time of day. These elements bring a feeling of immediacy to Minkoff’s work, or rather, a vivid impression of a moment about to slip away.

Due to the complexity of his technique, Tim Cross’s artwork enthralls on two very different levels. At a distance, the narrative elements of the work draw viewers’ attention, such as dreamlike architectures decorated with geometric patterns and lush flora, plus the odd flying machine. The titles of certain pieces, such as “God’s Grove” and “Lusus” (planets in Dan Simmons’ “Hyperion” series) draw an explicit connection between Cross’s art and works of science fiction. Inspired by Robert Rauschenberg’s Hoarfrost series from the mid-1970s, Cross transfers images onto diaphanous silk, whose quality of airy immateriality underscores the unreality of the imaginative settings he creates.

When viewers scrutinize Cross’s pieces up close, however, it’s the delicious interplay of appropriated and abstracted images that merit attention. In “Lusus,” a row of dark spires is, as it turns out, cobbled together from reproductions of some sort of schematic or technical drawing. What seems to be a colored blossom in “God’s Grove” in fact consists of pictures of spores or cells seen under a microscope, enlarged, Xeroxed, and reassembled to create the illusion of symmetry. In “The Flood,” which depicts a half-submerged, post-apocalyptic cityscape, ordinary bar codes form part of the implied architecture. Poetically, Cross constructs the ruined city out of fragments of print images, cut so small that the original subjects become utterly abstract, yet remain maddeningly familiar.

Daphne Minkoff and Tim Cross both co-opt the ordinary and present it back to viewers in potent, unexpected ways. What urbanites so easily overlook in the hustle and bustle of modern life, Minkoff has perceived out of the corner of her eye and dragged front and center in her pieces: a community and a way of life that are fading. Cross takes even the most banal print images, breaks them down, and delights in building strange new worlds with them, for, as he puts it, “Creating stories, maps, structures, and ships is how I satisfy my curiosity as I dream of a million years from now.” No people appear in these artworks, but by exploring real and potential cityscapes, Minkoff and Cross are essentially reflecting on human society—how we inhabited spaces in the past, and how we might do so in the distant future.

–Elisa Mader