Even as the US federal government renounces Obama-era efforts to improve relations with Cuba, the Art Academy of Cincinnati is displaying the results of several years of artistic collaboration between the two countries. That collaboration began in 2015 when M. Katherine Hurley and Jens G. Rosenkrantz, Jr. met with Manuel “Lolo” Alvarez, Ercadel “Sole” Sanchez, and Cesar Castillo Barrera to plan an art exchange that would grace two venues in Cincinnati and one in Havana. At the entry point of the Art Academy show we find its impetus: “In the current political climate of turning away visitors and talk of building walls, we as artists think it is better to build bridges.” Barbara Hauser embraced that thinking at the Red Door Project in March 2017, and the Art Academy continues the conversation by hosting Bridges Not Walls throughout November and early December. Soon the artists will share their compositions with each other and a larger community of viewers at the Havana studios of Rigoberto Mena. Showing the works at multiple sites over an extended period of time indicates an effort at sustained, wide-ranging dialogue despite foreign policies intent on shutting it down.

Trump has expressed his determination to curb “people-to-people” travel to Cuba while preserving the privileges of US corporations in the area, showing his simultaneous disdain for Cuban culture and his dedication to the prerogatives of American capital. Although Trump claims human rights concerns as his motivation for recent travel restrictions, William M. Leogrande observes that “the administration has shown no interest in human rights in Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, or the Philippines. On the contrary, the president has gone out of his way to praise and encourage leaders whose human rights records are far worse than Cuba’s.” The Castros have long resisted US attempts to influence political and economic customs in the country, and recent pronouncements from the White House will likely energize that resistance while undermining the goodwill the Obama administration tried to build. “The United States will pay a heavy diplomatic price in Latin America,” Leogrande explains, “where relations are already strained because of Trump’s incendiary rhetoric about Latino immigrants, the Mexican border wall, and the North American Free Trade Agreement.” Bridges Not Walls proceeds with precisely such tensions in mind, gathering perspectives that range from scathing appraisals to comic send-ups to lavish displays of generosity, all of it deriving force as much from contextual incongruity as agile technique.

The show discloses those perspectives through thirty-five image pairings, each including one work by a Cuban artist and another by an American. At times the visual interchanges yield clear rhymes, at other times startling counterpoints. Perhaps the most profound contrast appears in the pairing of Cuban Mayo Bous and Cincinnatian Donna Talerico, whose paintings signal the distance between rage and reconciliation, between disgust and the desire for healing. Bous’s “Guagua Trump” pictures the president leaning out the door of a speeding bus, his now iconic scream-face presumably hurling insults or warnings at whatever lies ahead. By no means in control of the vehicle, he nevertheless projects an aura of absolute authority. As the road rushes under the tires and the rear of the bus blurs, there arises the sense of careening recklessness that nicely characterizes the present administration in Washington. The canted angle of the scene only reinforces the prospect of coming calamity. Silhouetted passengers gesture wildly, though it remains unclear whether they echo Trump’s “America First” dogma or they mean to protest it. As the president’s leg whips in the wind, it becomes all too apparent that no one is driving the bus.

Given the warranted vitriol of Bous’s work, Talerico’s A Bouquet for the USA President comes as a surprise, denoting an extravagant gesture of kindness in an atmosphere of division. The flowers press forward in cloudy strokes, mingling an array of woodsy colors with traces of flame. The figure vibrates with life, its energy dripping from the buds and entering into the cream backdrop. The bouquet sits slightly off-center in the picture plane, the arrangement arcing over unfilled space toward the viewer, reaffirming the movement of offering. Reveling in excess, it overwhelms its vase and bursts the borders of the frame. Such excess may stand as a quiet critique of the recipient, as may the barely discernable evocation of a mushroom cloud. The poignancy of the painting derives not from those subversive undertones, however, but from its commitment to outreach despite present circumstances. In a show filled with bridge motifs, Talerico’s work has a bittersweet resonance due to the intransigence of its addressee, the unlikelihood of the gift being received or even noticed. Hanging just below Guagua Trump, A Bouquet for the USA President does not so much contradict its partner image as accentuate the breakdown in international reciprocity, connoting a quixotic attempt to engage an administration bent on outlawing engagement. The pairing with Bous, along with the sociopolitical context of the painting’s production, erases any trace of sentimentality.

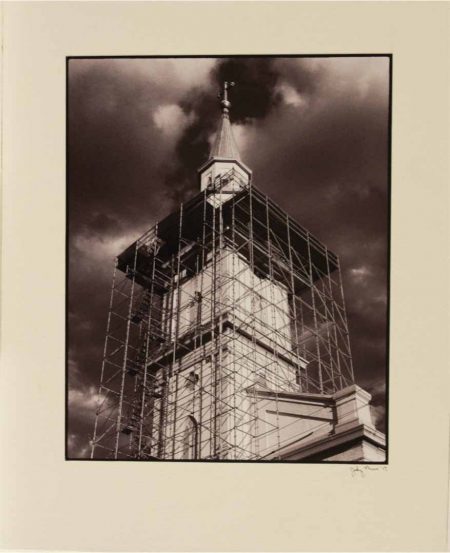

Coupling Bous with Talerico produces especially dense semiotic potential, and in that way provides a good sample of how Bridges Not Walls operates. The combination of Yunior La Rosa’s Cacería and Jody Bunn’s Transformations provides another. Whereas the first pair at once enacts and reflects on international political negotiation, the second places greater emphasis on formal harmonies. In Cacería we encounter a high-definition photograph of a machine gun bullet rising out of a lipstick case, the integration so seamless that we might not at first notice the dissonance. With its clean lighting and alabaster background, the image has the commercial sleekness of a fashion magazine. But as the bullet occupies the conventional space of the lipstick, the object connotes a certain violence embedded in superficial forms of beauty, a threat all too poorly hidden by cosmetic veneers. Transformations reiterates the movement of Cacería by picturing a church steeple emerging from a grid of scaffolding, reaching toward a sky that is brooding and heavenly in equal measure. The tapering tower parallels the strata of the lipstick holder, inviting us to seek out the tensions so present in La Rosa’s photo. Does the steeple’s ascent connote violence as well, especially given the weaponization of Christianity in the era of hardening borders? Or does it alter the logic of Cacería by advancing, like Talerico, an appeal to cross-cultural compassion despite the present cage of xenophobic nationalisms? The photograph gives us no way to settle the case, though it concentrates the ambivalence that runs like an electrical charge through the larger exhibit.

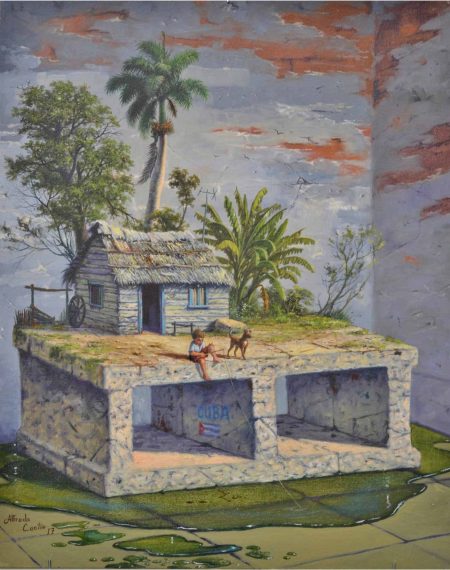

The works’ internal tensions run from the formal incongruities of La Rosa and Bunn to the surreal hallucinations of Alfredo Cecilio and Cincinnati-based Sara Caswell-Pearce. In Cecilio’s Pescador de illusions, for example, we enter a realm where rural and urban, inside and outside, relative weights and sizes have all been throw into disarray. A boy sits fishing near a thatched hut, his dog nearby as they lounge on a patch of earth. Yet the whole scene rides atop a single cinderblock, situated in a viscous puddle on the tile floor below. That puddle doubles as the lake in which the boy fishes, just as the sky transforms into the mottled walls of a kitchen or bathroom space. Inside the cinderblock we spy the graffito “Cuba,” the word and accompanying flag synthesizing the surrounding contradictions. Tensions of depth and scale run throughout the picture plane: a body at leisure also sits on the edge of a precipice; interior squalor swallows up country pleasures; harmony tangles with disorder. If we allow the sky to be only sky for a moment, the uncertainty still prevails. We cannot readily decide whether the painting depicts the multicolored shades of late afternoon or, as with Bunn’s Transformations, something more ominous.

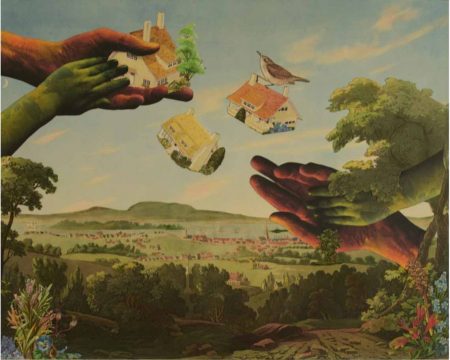

Caswell-Pearce’s Hands Across the Water matches Pescador de illusions by disrupting our sense of orientation with each new detail. Enormous human hands and slightly smaller green ones caress each other, or perhaps clap, while occasionally tossing houses across a wooded expanse. A similarly large bird either helps deliver the houses or snatches one from the giants in mid-flight. The scene comes to us suffused with play, evoking madcap symbiosis while simultaneously implying imminent peril, especially to the structures of bourgeois security. Haphazard as such play seems, the giants appear to keep their distance from the village, wreaking festive havoc without upsetting the local community. In AEQAI’s May/June 2017 issue, Jane Durrell characterizes such samples of Caswell-Pearce’s work as “magnificently executed, incongruity given dignity.” Hands Across the Water exemplifies this dignified eccentricity while constituting a remediation of Victorian postcards, reflecting Caswell-Pearce’s passion for nineteenth-century material culture, her creative attachment to “paper with a past” (Pearce). In her contribution to Bridges Not Walls, the conceptual and historical juxtaposition of materials embodies the show’s penchant for strange reachings, oddball efforts to connect in an environment that favors seclusion, clear demarcations, protecting the familiar against the unknown.

The show’s array of curious affinities produce effects that are by turns ecstatic and unsettling, depicting musical and architectural exchanges, corresponding palettes and visual styles, complementary geometries, analogous geographies, shared intensities of pleasure and grief, flags proud and portentous, Havana Club and Coca-Cola bottles shattering into each other. Shards fly in every direction as their separate sources become indistinguishable; the passion of the merger equals the force of its prohibition. While the defiant couplings of Bridges Not Walls make a highly specific geopolitical statement, they also have more general resonance as the US president expands the scope of international travel restrictions. In light of such tendencies, the show models the bonding that has yet to occur across a dense weave of borders, whether ideological, topographical, or manufactured. As the Trump bus rolls implacably forward, the Art Academy presents its small bouquet, holding no illusions that the gift will hinder the movement of authoritarian politics, but offering it nonetheless.

–Christopher Carter

Works Cited

Pearce, Sara. Paper with a Past. paperwithapast.com. Accessed 22 Nov. 2017.

Durrell, Jane. “Profile of Sara Pearce.” AEQAI, 10 June 2017, aeqai.org/2017/06/profile-of-sara-pearce/. Accessed 22 Nov. 2017.

Leogrande, William M. “Trump Has Set U.S.-Cuba Relations Back Decades.” Foreign Policy, 22 June 2017, foreignpolicy.com/2017/06/22/trump-has-set-u-s-cuba-relations-back-decades/. Accessed 22 Nov. 2017. contact.html