The Harvard Art Museums and curator Jennifer Quick have pulled off a minor miracle with “Analog Culture,” an understated, poetic show of heart through a lens of craftsmanship, careful discipline, and the wavering line between producer and artist. It’s rare to find a show that is at once pointedly educational, culturally searing, historically significant, and doggedly palatable—with a video installation kicker that adds another dimension of poignant questions.

The featured prints, on view through August 12, were created by Gary Schneider and taken from Harvard Art Museums’ recently acquired Schneider/Erdman Printer’s Proof Collection: a group of nearly 450 photographs printed over three decades by Gary Schneider of the Manhattan-based studio Schneider/Erdman, Inc. The show’s depth comes from the nearly archaeological care given to process in each object description. The viewer becomes insider to a photographic method quickly disappearing from the artistic landscape, and is encouraged to actively notice the painstaking collaboration that can take place between developer and artist. The artists’ names may be on the placards, but Schneider’s contributions are front and center, from paper choice to exposure time.

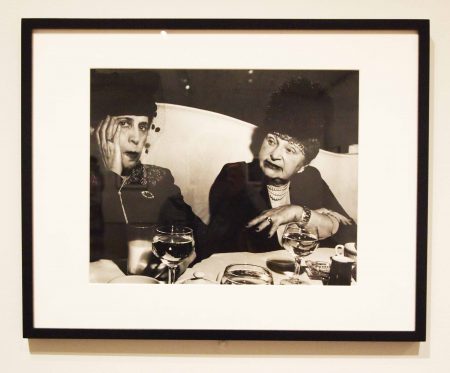

The photographs on display—about 90 black and white prints created between 1981 and 2001 (though the oldest images were taken nearly a century ago)—made me want to head to the gift shop to buy a postcard pack. Artists from New York and those visiting from around the world sought the lab for their prints. Stills from Madonna’s infamous 1992 “Sex” book show up, as well as Brian Lanker’s portraits of influential black women from the 1989 book “I Dream a World.” Many of the images appear to be so accessible and cool-looking, the exhibition could be glossed over as a standard New-York-nostalgia fest. Fashion photography, grand dames, a stately dog, even the Beatles—highly post-able.

But the social upheaval of the 1980s and 90s looms large in “Analog Culture,” colored mainly as the specter—or stark confrontation—of HIV/AIDS in the work of Peter Hujar and David Wojnarowicz. Era-defining pain lives alongside bright beach scenes. For example, a stately dog featured, Will, belonged to Peter Hujar. He had intended to give them as thank-you gifts to friends who had cared for him as he battled HIV. Hujar died in 1987.

You want to share these pictures, even as they tear your summer heart.

I don’t mean to de-fang these images—it’s just that yesterday’s controversy is today’s vintage-hip, in many but not all cases. While few would flinch at Nan Goldin’s 80’s drag queen portraits today, I heard a startled “oh my” from a patron who wandered too close to Wojnarowicz’s “Sex Series,” with its small pornographic stills inset into larger imagistic narratives that use x-ray techniques and text to illustrate the violence of the AIDS crisis. Schneider had to photograph the originals and carefully reproduce each print to ensure that the newspaper print would remain legible.

It is here, in this spirit of preservation and education, that the physical setting of the exhibition and A.K. Burns’ video installation, “Survivor’s Remorse,” comes into play. First, though, one must remember that positioning Harvard as the best institution for whatever area of study is being discussed is, of course, Harvard’s prerogative. As it is written in the exhibition description: “Altogether, [the acquisition of the Schneider/Erdman Collection has] reinforced the museums’ place as a primary site for the study, research, exhibition, and interpretation of contemporary photography.” Visiting the Harvard Art Museums (plural because there are technically three, in the same complex) is to see its exposed, glassed-in fourth floor, a key part of its recently completed years-long renovation. Burns’ installation is separate from the main exhibition, located in the Lightbox Gallery on the fifth floor: from that glass crow’s nest, the viewer sees not only the nine screens of her piece, but bottles of ancient pigment and workshop space where students, artists, and conservationists work, though none were present on a summer Saturday.

Those workspaces and pigments are a significant part of Burns’ piece—it was commissioned by the museum, and she filmed within the same space that we gaze upon as viewers, among other locations. But “Survivor’s Remorse” derives its power from multiple places, most notably David Wojnarowicz’s marginalization in life and death as a victim of AIDS. Even as he garnered acclaim, he was poor and even homeless at times, without health insurance. His art sells for thousands now, as we see in a Sotheby’s auction in the piece. We value art long after the artists’ death without valuing them while they are alive.

This sentiment comes to life chillingly as we watch a painstaking restoration of a chipped painting with state-of-the-art equipment, as a voiceover of David reciting his poem, “When I Put My Hands On Your Body,” plays. The poem is printed large in the main exhibition, and was meant to be part of a larger series, but Wojnarowicz died after completing only two. (The print lived in Schneider and Erdman’s house for years afterward, as a way to remember their friend and collaborator.) In it, he pleads for life to be preserved, given a name and appropriate value to a beating heart, but what we value is the life of the art, not a human person. Another voiceover talks about “super flies,” genetically engineered fruit flies whose lifespan is doubled. We can devote that energy to flies, but not dying people.

These associations are poetic, not graphic. Burns’ piece deconstructs the grid of nine screens by placing one in a wooden crate, with requisite padding and “handle with care” labels. Despite these trappings, it still resembles a casket, most pointedly as Wojnarowicz’s funeral procession plays in the opening moments isolated to that one screen. The procession banner along with his name and birth/death dates, reads: “DIED OF AIDS DUE TO GOVERNMENT NEGLECT.” Handle the art with care—but not the artist.

I’ve always said that I love poems because they don’t have to be certain: good poems unburden readers from certitude while elegantly layering questions like rich topsoil. “Analog Culture” achieves the same effect, especially paired with “Survivor’s Remorse”: how can we value artists while they are still living? How can we keep Schneider’s art of developing alive—and should we, in this technological age? Why don’t we devote as many resources to supporting active artists as we do to art preservation? Now that HIV/AIDS is not necessarily a death sentence, at least in the U.S., how can we make sure that this type of marginalization doesn’t manifest in other ways?

In this show, it’s the lens, the paper, the process, that filters our perception. Simply a printer taking stock of images powerful, fun, and historic. Send the postcard, think the thought.