Cincinnati’s National Underground Railroad Freedom Center brings the history of US slavery into conversation with human rights abuses across varied national and cultural contexts. From October 1, 2016 to January 23, 2017, the museum hosts an exhibition of works by Zanele Muholi, a Johannesburg-based photographer who mounts stirring condemnations of violence against Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex (LGBTI) people in South Africa, as well as the racist labor relations that trouble her home country. Her show “Zanele Muholi: Personae” blends the LGBTI documentary project “Faces and Phases” with “Somnyama Ngonyama,” a series of self-portraits centering on family, resistance to the body-scripts imposed on black women, and the politics of work. A self-identified visual activist, she makes her arguments through gelatin silver prints, which affirm her dedication to justice and her unflagging technical rigor. Muholi’s civic artistry helped initiate the Forum for Empowerment of Women (FEW) in 2002, and later sparked Inkanyiso (www.inkanyiso.org), an international venue for queer media. While keeping a remarkable schedule of showings, she remains a visible participant in social movement discourse while also making time to hold photography workshops for South African women (“Zanele,” Stevenson). “Personae” affords Freedom Center visitors an intimate glimpse of her catalogue, which not only challenges persistent forms of social division in South Africa but refuses distinctions between documentary and advocacy

That refusal fits her corpus especially well to the theme of the 2016 Fotofocus festival, “Photography, the Undocument.” The festival takes a nuanced approach to the photo as a historical document, “questioning its claims to objectivity and observing its tendency toward subtle fantasy” (Fotofocus). Muholi reproduces numerous tendencies traditionally associated with documentary, including the effort to record lived experience for coming generations and thus guard certain populations against historical effacement. Such efforts code the photograph as a testament to being and a contribution to archival memory. But in focusing on a population that experiences not only the danger of historical diminishment but an immediate, deadly threat from its antagonists, Muholi insists on the continuity of documentary with partisan discourse and collective action. In one way, her images exemplify the “undocument” by disturbing the genre’s purported “claim to objectivity”; in another way, they question whether that claim ever held legitimacy, and whether the negative prefix in the undocument entails a certain redundancy. She indulges in fantasies both subtle and extravagant while never shedding the mantle of documentarian.

As she embraces that title, Muholi rejects the luxury of distance. In an interview with Vuyiswa Xekatwane, she explains that

I haven’t been documenting the LGBTI community as an observer, I document it as a member of the community […] I speak, produce and document these visuals so that those who exist today and will be born tomorrow can have access to a factual visual history of the South African LGBTI black community.

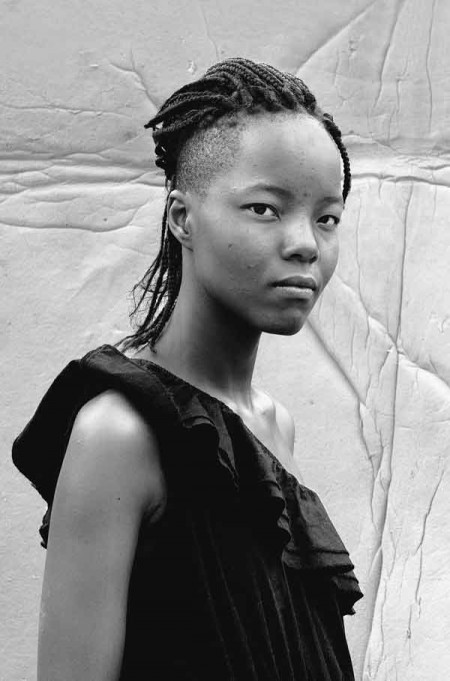

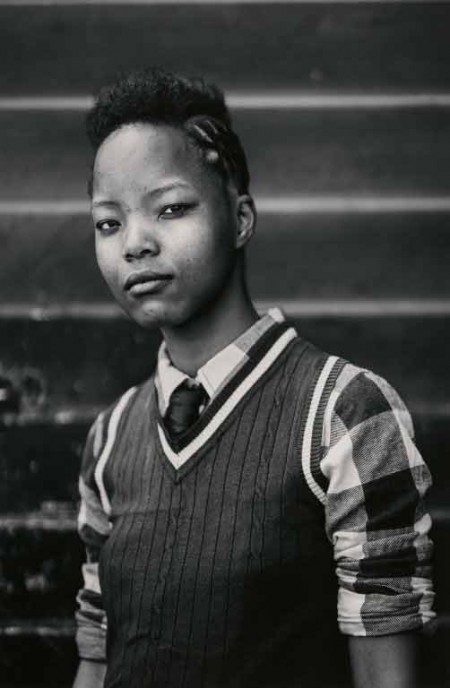

As visitors enter the “Personae” exhibit, they first encounter a selection of pieces from “Faces and Phases,” a project she began in 2006. That project concentrates on LGBTI identities, gathering serene black-and-white portraits of Muholi’s friends or people for whom she feels political affinity. Although the portraits sometimes exist in pairs, and sometimes in grids of as many as twenty-seven images, they generally situate the evolving self within a coordinated social sphere. Violence permeates that sphere, though the subjects of the portraits face it with solemn composure and even defiance. The violence includes a history of “corrective rape” wherein perpetrators attempt to enforce gender norms by brutalizing nonconforming subjects (“Zanele,” Artsy; Hunter-Gault; Wortham). The singular photos exhibit a kind of placidity, yet in combination they pose a determined challenge to sexual hegemony. Muholi features the same people in multiple photographs, the variations in their attire and hairstyles spurning the gender codes their assailants attempt to mandate. With such techniques, she not only bears witness to LGBTI community but also works to build and strengthen it.

She began recording oral narratives of violence in the early 2000s while also taking pictures that would speed the initiation of “Faces and Phases.” The interviews occurred against a contradictory backdrop, given that South Africa’s Bill of Rights pioneered the explicit prohibition of sexuality-based discrimination, and yet the kidnapping, rape, and murder of LGBTI people remain all too common occurrences even today. Charlayne Hunter-Gault contends that despite the Mandela government’s defense of human rights, multiple rapes occurred every minute in 2009 South Africa, and lesbians still undergo violation twice as often as their heterosexual counterparts. Many victims fear going to the police, so that “the number of sexual offenses that occur in a given year is nine times as high as the number reported” (Hunter-Gault). The subjects of Muholi’s portraits often have distinctively harrowing stories to tell, but her evocation of a growing visual community also signals solidarity with those who have not yet broken silence. It signals a project that is still gaining traction, and one Muholi foresees continuing throughout her career.

That career involves bringing a social movement ethic into the space of the gallery. Rebuking forms of cultural and economic elitism that sometimes permeate gallery culture, she sees the museum as a place of dissidence. “Fine artists deal with finery,” she tells BBC’s Bidisha,

but I deal with painful material […] Looking at where we’re at right now in the struggle [against homophobic violence], there’s nothing to laugh at, there’s nothing to enjoy except when one is intimate with her lover. I ask my sitters to think about the situation, think about being black, being a lesbian, being a woman.

While partly revealing the impetus for those sitters’ contemplative expressions, she challenges viewers not to divorce the beauty from the suffering, not to extract the person from the social milieu. When Bidisha questions whether the showing constitutes a bourgeois appropriation of her efforts, Muholi insists on the images’ potential to transform the audience: “Showing [my work here] is political. Especially in this space. The very same kind of posh people who come here are the unconverted who should see this work.” She then layers her reflection on audience politics with attention to apartheid in the South African art world: “Black people, people of colour were excluded from these kinds of spaces for years. So now we’re here and we’re showing the way for other artists” (Bidisha). Her photos thus work to thwart many visitors’ interpretive assumptions, as well as the hateful traditions that inform those assumptions, while also inspiring those who share her passions to visualize new creative pathways.

Zanele Muholi

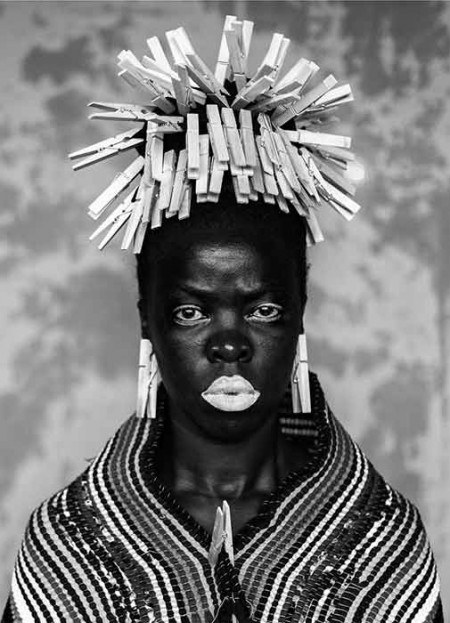

While showing such dedication to political and artistic fellowship, Muholi also devotes considerable energy to self-investigation. As visitors to “Personae” cross through the gallery space, they notice the artist staring back from multiple portraits in “Faces and Phases.” They then enter into a smaller room filled entirely with images of Muholi, variously adorned with scarves, shawls, necklaces, earrings, and crowns, her skin-tone drained or darkened by lighting and makeup, her body sometimes covered and other times almost fully exposed. She calls the assemblage “Somnyama Ngonyama,” or “Hail the Dark Lioness.” The project began during a 2012 residency in Italy, and has since become an effort to compose 365 interconnected images reflecting the days of the year (Jayawardane 5). As with “Face and Phases,” the photographs have an arresting aesthetic, addressing us with a calm, brutally direct gaze almost before we can level our own. And like the first room, the second confronts pain that is at once cultural and familial, historical and immediate.

The pain comes in part from the collision of race and gender ideology in South Africa. While “Somnyama Ngonyama” ostensibly concentrates on self-portraiture, it also constitutes a meditation on the experiences of Muholi’s mother, Bester, who worked as a white family’s housekeeper for more than forty years. The curtains, tapestries, pop-tops, and clothespins the daughter wears have a glamorous and occasionally regal quality, but they also connote the mother’s lifetime of poorly compensated domestic service (Jayawardane 20, 23). The extravagant portraits of the artist, like the more subdued images of her LGBTI friends, situate the individual within a swirl of visual discourses, at once reproducing and calling shame on longstanding tropes of exoticism. As the pictures attend to how blackness and gender mediate privilege, Xekatwane suggests that they also investigate “the culture of selfies.” If that is true, it is not merely because Muholi participates critically in the international tendency toward reflexive camera work, but because she exposes how culture circulates through images, with the self-image expressing that circulation rather than eluding it. But however deeply immersed she is in those currents, she nevertheless finds opportunities for dissent. She appropriates the clothespins for her own, unsanctioned purposes, sabotaging Western stereotypes while channeling the materials of everyday oppression into something theatrical, magnificent, nearly hostile.

Her photographs challenge both the privilege of many gallery visitors and the history of apartheid from which the images derive. While wrangling with selfie culture, they address even more aggressively the memory of “passbooks” in South Africa, the photo-documents that permitted blacks to travel in white-dominated areas for limited periods of time (Wortham; Jayawardane 8). Those passbooks aided the process of racialized labor exploitation, permitting blacks to reach the workplace while ensuring that they not linger after hours. Working conditions were deadly, especially in the mines, which continue to embody labor injustice and health risks long after the dismantling of apartheid. She confirms her sensitivity to such issues in an Aperture interview with Deborah Willis, where Muholi praises Ernest Cole’s 1960s-era photos of mineworkers as compelling protest documents. Cole photographed workers who were subject to frequent humiliations, people who were “naked, discounted to nothing, nameless,” she explains. “That was visual activism, but [Cole’s contemporaries] did not regard it as anything of that sort, even if people at that time were killed and forcibly removed” (Willis). Muholi links her activism to Cole’s, though her modes of resistance are more oblique. Instead of covering working conditions, she subverts the phenomenon of worker identification papers, displacing lifeless, bureaucratically orchestrated facial images with ones that radiate self-determination. Whereas the passbook connotes exposure to the authority of whiteness, “Somnyama Ngonyama” refuses to submit to it.

In that way, the second room continues to exemplify Muholi’s production of the “undocument” by reminding us of the politics of South African travel credentials. It also reaffirms the show’s connection to the Freedom Center’s human rights mission, and the museum’s contributions to ongoing struggles against institutionalized racism. After seeing how “Hail the Dark Lioness” coheres with that project, the visitor must cross again through “Faces and Phases” to re-enter the Center’s collection of materials memorializing the Underground Railroad. The layout of “Personae” situates Muholi’s self-examination between encounters with a threatened but dignified collective, a community of whom she is participant-observer. Both segments of the show insist on recognition—of singular persons and their solidarity, of poise and pride in the face of violence. But they also call attention to the historical and structural inequalities that confer on some bodies the right to recognize and others the status of object. Refusing the affiliation of documentary work with some impossible idea of nonpartisanship, Muholi documents the racial politics of the monitoring gaze. The photographs stare back at the spectator, who, like the personae on display, constitutes but one node in a social mesh where race, gender, sexuality, and labor constantly mediate the flow of power. Muholi cuts against that flow, but only as part of the critical public she records and enacts. The physical arrangement of the show, running through the social field into the self and back again, tells us that.

–Christopher Carter is an associate professor and Composition Director in the English Department at the University of Cincinnati. He is the author of Rhetoric and Resistance in the Corporate Academy (Hampton Press, 2008) and Rhetorical Exposures: Confrontation and Contradiction in US Social Documentary Photography (University of Alabama Press, 2015).

Works Cited

Bidisha. “Pride and Prejudice: How Zanele Muholi Documents South Africa’s LGBTI Community.” BBC Arts, 15 Apr. 2015, http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/ articles/12VHc6SJ36ySTKlCSYG1swY/pride-and-prejudice-how-zanele-muholi-documents-south-africas-lgbti-community. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.

Fotofocus. “Fotofocus Announces Theme of Fotofocus Biennial 2016: Photography, the Undocument.” FotofocusCincinnati, http://www.fotofocuscincinnati.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/FotoFocus-2016-Photography-the-Undocument_ PressRelease-FINAL-150407.pdf. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.

Hunter-Gault, Charlayne. “Violated Hopes: A Nation Confronts a Tide of Sexual Violence.” New Yorker, 28 May 2012, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2012/ 05/28/violated-hopes. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.

Jayawardane, M. Neelika. “Embracing the Dark Lioness’ Call.” Ed. Sophie Perryer. Trans. Hélène du Preez and Raphaëlle Jehan. Hansa Print, 2016.

Willis, Deborah. “Zanele Muholi’s Faces and Phases.” Aperture, Spring 2015, http://aperture.org/blog/magazine-zanele-muholis-faces-%C2%9D-phases/. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.

Wortham, Jenna. “Zanele Muholi’s Transformations: A Photographer Known for Taking Striking Portraits of Members of the Black Queer Community in South Africa Turns the Camera on Herself.” New York Times, 8 Oct. 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/ 2015/10/11/magazine/zanele-muholis-transformations.html?_r=0. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.

Xekatwane, Vuyiswa. “Conquering Fears of Queerness: Zanele Muholi’s ‘Somnyama Ngonyama.’” 10and5, 20 Nov. 2015, http://10and5.com/2015/11/20/conquering-fears-of-queerness-zanele-muholis-solo-show-somnyama-ngonyama/. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.

“Zanele Muholi.” Artsy, https://www.artsy.net/artist/zanele-muholi. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.

“Zanele Muholi.” Stevenson, http://stevenson.info/artist/zanele-muholi/works. Accessed 13 Nov. 2016.