On the quiet Tuesday that I visited the “Dressed to Kill: Japanese Arms and Armor” exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum, there were only a few people in the gallery, mostly middle-aged men. They were carefully studying the 11 suits of armor on view, but were equally intent on the many, many weapons on display: a 7’ bow and arrows; swords, sword fittings, and scabbards; polearms (blades mounted on poles), weapons hidden in canes, fans, and chopstick cases; matchlock guns and gun-powder flasks, etc. One unusual weapon is a sokutōku, a container for an eye-irritating powder, a Japanese version of pepper spray.

While the craftsmanship of the weapons is exquisite, they didn’t come close to engaging me as they obviously had these men. It must be a guy thing. It’s too bad the show closes on May 7, 2017, or I’d recommend it as a perfect activity for Father’s Day with lunch in the Terrace Café with its new executive chef, Sean White.

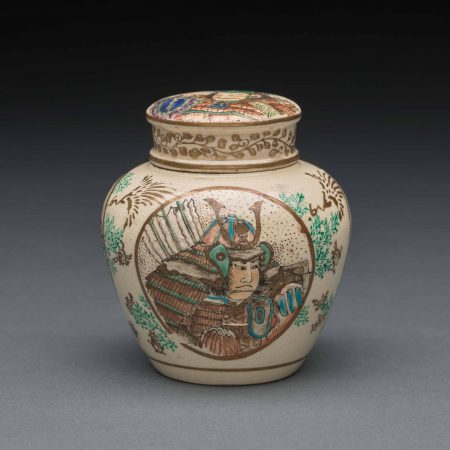

The exhibition is supplemented with ceramics, such as this Covered Jar, but also paintings and prints, textiles, calligraphy, etc., to lend context to the armor and weapons, which date primarily from the 15th to19th centuries.

Samurai means “one who serves” and describes the middle and upper ranks of warriors. Originally they were provincial soldiers who defended the shōgun or supreme ruler. Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a son of peasants, became a grand minister in 1586 and created a permanent and hereditary samurai caste. Two years later, the right to carry swords was restricted to samurais, separating them from the lower classes of farmers, artisans, and merchants. Samurai lived by bushidō, a code of chivalry that included goodness, honor, loyalty, courage, honesty, respect, and compassion. In medieval Europe, they would have been knights.

The samurai lost their exalted position after the civil war against the Tokugawa regime and imperial rule was re-established in 1867. But they became romanticized, a bit like the cowboys of the Old West.

Before looking at the armor, obviously the stars of the show, start with Landscape with Warriors from a folded book; it documents the turning point in the 1600 battle that established the Tokugawa shogunate (1600-1868), the last feudal military government in Japan. The delicacy of the washes and the spare and sure line belies the ferocity of the battle. Two horse-mounted warriors charge at each other with polearms extended, reminding me of medieval jousts in Europe. Foot soldiers support the samurai by using polearms to cut the leg tendons of the horses. In the center of this section, a pitched battle is taking place, but the unknown artist has inserted a serene landscape with blossoming trees.

It is astonishing that no matter how elaborate the armor is, it was intended for battle. With every part of the warrior covered from helmet (kabuto) to face mask (menpō) to hand armor (tekko) and thigh guards (haidate), it is hard to imagine how these soldiers could move at all. But look at some of the energetic images in the works on paper in the exhibition, especially the three color woodcuts by Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861) of The Last Stand of the Kusunoki at Shijōnawate. The samurai advance with determination in swirling garments amid a fusillade of arrows. Even though the images are static, you have an idea of how the warrior moved while wearing armor.

Despite how bulky the armor looks, it was actually relatively light and flexible. Some parts could be folded to fit in a box like the 21 ½” x 15” x 15” leather-and-wood one shown here.

It is impossible to single out one suit of armor as superior as they are all frankly stunning, but I was drawn to one late 18th-century suit. On its chest protector (do), black doeskin, which is lacquered to weatherproof it, is stretched over iron plates. Perhaps representing the armies engaged in battle, two pewter-colored waves, with incised detail, rush toward each other. The larger one on the left, silhouetted against a golden disk representing the sun, a symbol for the emperor, is about to overwhelm the other. The crests of the stylized waves are curled like claws. On the back, there are hinges that aren’t so different from what might be found at Home Depot today. The menpō is rather comical with an enormous nose, and a Groucho Marx-style mustache obscures its toothless mouth. Since these types of moustaches made of hair could block the samurai’s downward glance, they were replaced with incised markings of the lip and chin.

The decorative patterns on the other pieces of this suit are variations of grids. The haidate, which look like a hockey goalie’s thigh guards, are a wonderful checkerboard of oblong plates, alternating golden and dark lacquered metal, laced together. The sleeve guards (kote) have dots arranged in a grid. Despite the exquisite design and craftsmanship, befitting a high-ranking samurai, this armor was made for battle.

Children’s clothes that are miniaturized adult apparel are always cute, but I doubt if this early 19th century Child’s Suit of Armor (warabase) could ever be called cute. It was probably made for a 13-year-old boy who was entering manhood. In some families, boys were taught to fight, to gain experience and to earn the loyalty and respect of their retainers. Other families forbid their sons from entering combat. The beautifully stenciled doeskin of the do, the gilded iron helmet patterned after the cloth headdress (eboshi) of the imperial court of the Heian period (794-1185) worn by young men who had completed the coming-of-age ceremony, and the exquisite construction suggests it was commissioned by a wealthy samurai family.

As I already mentioned, there are plenty of weapons. At the cost of eliciting a groan, I think it’s overkill.

From the late Heian (794-1185) through the Kamakura (1185-1392) periods, mounted archery was the most respected form of Japanese warfare. The samurai used a type of long bow (yumi) that maybe the longest in the world, and swords were used for hand-to-hand combat.

The samurai swords on view are marvels of both technology and artistry. This sword was attributed to Bizen Masamitsu, who was a member of the Bizen school, one of five regional schools of sword making. Long swords, made before the 16th century, were often shortened, as this was, so they could be carried more easily and drawn with one swift motion. The cutting edge shows the cuts and nicks from past conflicts and sword polishers carefully preserved them as they added to the sword’s history and value. The fittings were made during the Edo period (1615-1868) and feature chidori (plovers), migratory shorebirds, which are auspicious symbols of perseverance because they overcome high waves and stiff winds to migrate.

Portuguese traders introduced the matchlock firearm in the mid-16th century, and it altered warfare completely. Foot soldiers could be taught to shoot more quickly than mastering the polearm and sword, but the sword remained the weapon of choice for high-ranking samurai.

The Meiji period (1868-1912) ended the elevated status of the samurai class. They were no longer allowed to “open carry” swords, however, many felt entitled to do so. To circumvent the prohibition, blades were hidden in everything from fans to canes (shikomijō). Samurai carrying shikomijōs appeared to be adopting Western styles, a goal of the Meiji rulers.

The superb craftsmanship and the lavish yet restrained decorative accents of the objects make warfare in Japan from the mid-13th– to 19th-century seem romantic. Will today’s Kevlar vests and AK-47s ever acquire that aura?

–Karen S. Chambers

“Dressed to Kill: Japanese Arms and Armor” through May 7, 2017. Cincinnati Art Museum, 953 Eden Park Drive, Cincinnati, OH 45202. 513-639-2954, www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org. Tues.-Sun., 11 a.m.-5 p.m. This exhibition is ticketed: $10 general admission, $5 college students (with valid ID), $5 children 6-17, free children 5 and under and members. Tickets are available online and at the Visitors Service Desk.