Up, then down. Up, then down. And now, up again. Saul Steinberg’s “Mural of Cincinnati,” having adorned the walls of the Terrace Plaza Hotel’s Skyline Restaurant (better known as The Gourmet Room) from 1948 until it was sold, and then the walls of the Cincinnati Art Museum until it was walled in to mount the “Treasures from the Tower of London” show in 1982, is back on public view. It’s been studied, documented, and so carefully restored by the Museum that you can see the artist’s pencil lines beneath the paint. You can wander along 75/89ths of Steinberg’s work–14 feet of the original have disappeared somewhere along the way–in the long, slender Schmidlapp Hall off the main lobby of the Museum. The second of seven murals that Steinberg created in the 1940s and 1950s—and the only one that can still be seen within a thousand miles of its original location—it was the last one for which he did all the labor himself.

Though Steinberg seems to have visited the city in the late 1940s to get inspiration, you won’t see much of the city you know. There is a spidery and elegant version of the Suspension Bridge (which is being traversed by pedestrians, vehicles, horses, and dogs) and a rendering of the Tyler-Davidson Fountain, almost lost amongst a crowd of invented statuary and monuments and memorials. A muddy river runs in the vicinity of the city, hosting a procession of flatboats, paddle wheelers, and barges that tick off the city’s historical connections to its inland waterway. There is a fantasy version of the Mt. Adams Incline that Steinberg must have seen shortly before the last of Cincinnati’s mechanical accesses to its hillsides was shut down in 1948.

But it’s not a portrait of the city. There’s a railroad train close to the mural’s center but the terminal is a red brick Beaux-Arts affair, not our Deco Union Terminal. There are many impersonal multi-storied buildings of the sort you might find in a lesser European capital, rendered in extreme perspectival views. The modernity of the city is attested to by a traffic light, a highway sign, and an occasional automobile. Otherwise, it could be an urban fantasy from a previous century. What you also won’t see are people gathering in public spaces—or even private ones–or practically anything about the lived tumult of urban existence. Steinberg’s city might as well have derived its image of civic life from the paintings of de Chirico.

If you want to see people in the mural, you’ll find them dancing. Executed in his calligraphic hieroglyphs, larger than life-sized men and women are in each other’s arms. The men are slightly smug but otherwise expressionless as they take women out for a turn across the dance floor. Even the gentleman (like all the rest, wearing full evening dress) leading his partner in a deep dip is doing it in the most professional way, as if to instruct others rather than for sheer joy or his own animal energy. Sophistication has come at a price. The women are equally poker-faced and are virtually all wearing hats and heels. They are all, quite literally, statuesque. One woman is dining, and she is eating alone (except, it appears, for her cat). She might be Cincinnati’s dowager empress with wine glass in her hand and a cigarette locked between her fingers. Her veil makes her unapproachable and her hat is as tall as her body. She is bedecked with jewels, echoing the motif of a geometric shape that sparkles dazzlingly, and which we see on women’s wrists and fingers, on top of hats and buildings, and in people’s eyes. The whole mural was designed, of course, to present ninety feet of decoration for a pretty posh restaurant, but it’s fair to say that in Steinberg’s Cincinnati, if you’re not dining or dancing, you are, quite literally, nothing.

Looking at the two Steinberg exhibits in town just now—the other, a collection of some twenty-five graphic works at the Solway Gallery covering a half-century of art—I was surprised to find his work chillier than I remembered it. I can see in his combination of angularity and elegance that he is one of the most important and idiosyncratic draftsmen of his era. If I’d still been an undergraduate in 1976, I would have had a poster of “View of the World from Ninth Avenue” on my wall, and I loved his various pictures of hands drawing themselves. I think I wanted to think that I was in on the joke. But there is as much edge as elegance in his loopy geometries and there is something depersonalized about his urban hieroglyphics.

I think that Steinberg tends to draw you in with his unbridled love of mark-making. He relishes the designed environment, as large as architectural imagination allows and as small as cigar bands. There is a joy that is sometimes infectious at the pleasure of the doodle. In “Speech,” a 1972 lithograph, the teeming jumble of calligraphic word-like scribbles are twisted into a shape that is the cartoon world’s most elegant speech bubble ever–almost sculptural in its layout. Famously, he called himself “a writer who draws,” but the words that he draws seem to ceaselessly proliferate, leaving us with walls of shapes that defy an audience, and perhaps mock it, an audience that might well be us. At the entrance to the show at Solway is a poster for a 1968 Solway show of Steinberg drawings when his gallery was still called “Flair Gallery.” People—designated by vertical Rorschach ink-blots—gather in front of scribbles and cross hatches on the walls, surrounded by more voluminous lines of Steinberg’s elegant, never-quite-readable script. This, we are told, was Steinberg’s take on the art world: “indistinguishable people looking at unintelligible objects.”

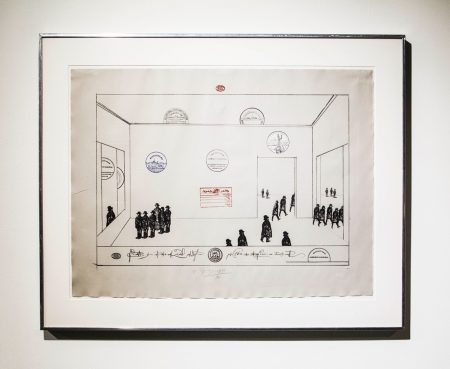

The Solway show features a related color lithograph, “The Museum (2)” (1972), where identical people in hats and heavy overcoats migrate in small groups in a determined lockstep from gallery to gallery. (I wonder how he might have rendered the movement of crowds at today’s museum blockbuster shows.) They might as well be commuters or refugees, though they also seem to be most like inspectors. They cast no shadows: they are perhaps from the world of dreams, or perhaps like the drawings that they are, they are nothing more than weightless, substanceless marks on a page. The two adjacent galleries might as well be empty; the room we can see is dominated by a large work that might be a triptych or might be a hole in the wall to let this group see into the next room. In any case, a figure in hat and heavy overcoat looks back at them. The remaining works in the room are versions of rubber stamps—Steinberg’s deliberate way of depersonalizing the visual world with their implications of bureaucracy, deadly routine, and even totalitarianism. He frames the image and gives it a calligraphic caption, as he often does, along with an additional rubber stamp or two. I see that part of the point is that the art world can be an authoritarian business, though it is hard to see why people subject themselves to such joyless rituals.

Part of the answer might be found in an etching like “Rabbit” (1984) where a squiggly rabbit looks cautiously out from inside the head of a well-walled self. A rabbit is loose amidst our schematics, and it does not like what it sees through its peephole. Our impersonality is willed; we are oppressed by our own mind-forged manacles. Inside those impassive, armored exteriors we’ve constructed, we’re less mechanical—and better drawn. One of many works that debunks male authority, it suggests that both rabbit and robot are isolated; there is nothing in the realm of sociability that can help them.

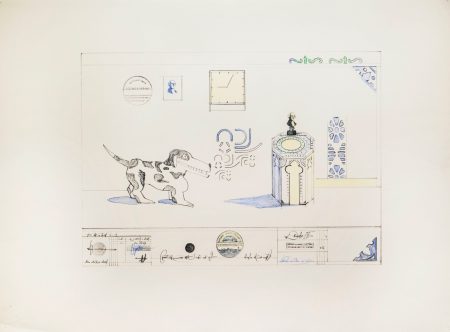

By and large, in Steinberg’s world, people dissociate. This is the way we live our lives, Steinberg seems to argue, and we arrange our domestic spaces accordingly. In “Untitled,” a lithograph from 1966, a dog stands in a living room in perfect profile amidst the things with which its people have surrounded themselves. On the wall is a clock (another form of hieroglyph), a framed picture of Washington, and a rubber stamp, Steinberg’s familiar abbreviation for other visual material, all equally spaced. The wildest thing in the picture is the dog, and it is speaking. But it is speaking in dog, and all we can see are the hieroglyphs of its barking, perfectly eloquent but completely unreadable. It may even have more in common with the rhythm of the Asian furniture that decorates the room than with the world of our culture.

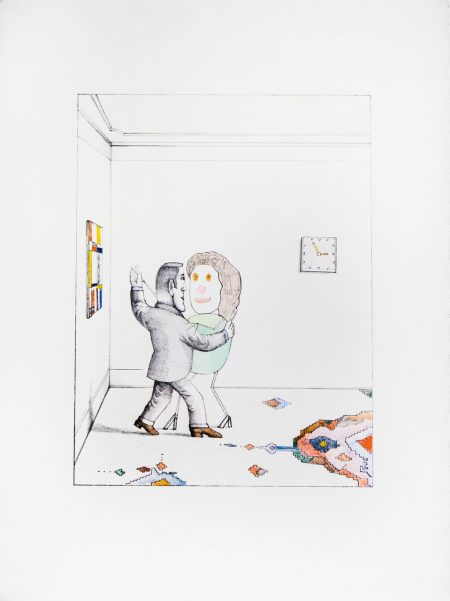

Steinberg’s people seem determined to preserve the space around themselves and to keep themselves as fundamentally discrete beings. In the 1996 etching “Ten Women,” there are ten cartoon sketches of females in two registers, done in a range of styles meant, I think, to recall how women are represented in the work of other artists. But they all face out to be seen by us, and have no interconnections between them, each one relatively compartmentalized in space. It would be fair to mention that women seem to be something of a puzzle in Steinberg’s work. They are likely to be formal and overbearing (heels and hats) and unapproachable, like the dining woman in the CAM mural. In “Dancing Couple,” a lithograph from 1965-74, a man and a woman are taking a spin on a living room rug. He is a well-drawn and elegantly shaded parody of the Hollywood leading man type. She is a child’s drawing, a stick figure with a balloon body and a blob face. The implication seems to be that she has created him in her mind in the model of her knowledge of men, and in line with her fantasies and desires. The man has presumably done the same, creating the woman in the infantile image of his knowledge, fantasies, and desires. Elsewhere, there is more of a sexual rawness. In “Legs,” a photoengraving and etching from 1992, a female figure is striding off. She has no torso—her head is attached directly to the waistband of her microskirt which floats above her long, muscular legs. (Such a figure appears in two other works at the Solway show.) She is followed by a strangely androgynous figure, wearing a general’s hat and tight military pants but who has long, coiffed hair, and whose high boots have high heels. Without knowing more about this strange and interesting image, it also has to be noted that this is what passes for a couple in Steinberg’s world.

It may be that nature has something of an answer to the problems of culture’s authoritarianism and humans’ feeble defensiveness. In “Tree Bauhaus” (1964), a line of four people have left the harsh angularity of a specimen of modern architecture to stand by the roots of a towering tree. If the building is drawn with lines entirely characteristic of Steinberg’s fantasies of the created world, the tree’s leaves and the sky behind and all around them are irregular in shape and density; through the leaves, one can see a bluer sky. The tree trunk has its own harsh angles, and bears calligraphy and a rubber stamp. Is nature in danger of becoming Bauhaused? Are the lines of our culture a kind of contamination?

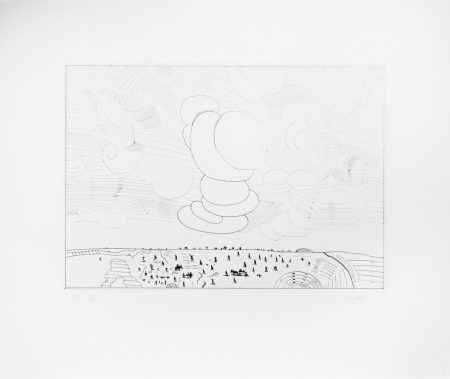

A work like “North Dakota,” and etching and drypoint from 1984, suggests not. On the flat land beneath the immense sky of the Great Plains, people do what they do in Steinberg’s prints: they dissociate. Preserving that buffer of space between them, they parade randomly or settle in and make an effort to farm. But they are dwarfed by the magnificence of the sky, which is shaped by marks representing clouds and wind and the powerful forces of the air. There are rows and columns and sticks and fragments, and huge donuts and columns and circles. Humans seem to have negotiated the spaces they choose to keep between themselves, keeping intimacy and connectivity at arm’s length. Nature here isn’t convinced, or even interested. For Steinberg, a man mad about making marks, he seems here to have found the space to spread out, the scale that allows nature to absorb all the marks the artist wants to make without their ever becoming fussy or cranky or selfish.