The Weston Art Gallery’s Beacon exhibition elicits a range of meanings from its title. Beacons in the show are by turns literal and symbolic, concrete and conceptual. Gallery notes invite us to watch for “luminary individuals, institutions, and ideologies” while remembering the sense of beacon as “a kind of warning.” Bringing together ten lens-based artists who perform variations on the show’s theme, curator C. M. Turner affords us an experience of rich aesthetic diversity and timely politics. While ideas of guidance and safe harbor inform various pieces in the exhibit, it is the warning that radiates most insistently, coating even the show’s more sanguine entries with a layer of disquiet.

Some of those hopeful entries appear in Bruce Bennett’s Love Series, which celebrates the “magic” of Blackness and the healing qualities of love, both romantic and communal. His models convey a combination of dignity and sensuality: they are statuesque but supple, self-assured and yet dreamy-eyed, contemplative. They engage with the viewer and perhaps with each other across the gallery space, but they also engage in self-embrace. Fully at home in their bodies, they convey a warmth that lends the prints a rust-colored glaze along with contrasts of burnt orange, gold, and concentrated blackness. Silken material surrounds the models and inflects the texture of the images.

Photo courtesy of the artist

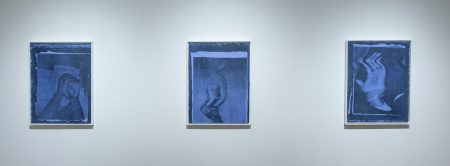

But viewers can only linger with those textures for so long, especially given their proximity to Noel W Anderson’s Blak Origin Suite, which hangs several feet away on the Weston’s lower floor. Like much of his work, the trio of handmade paper objects addresses Black masculinity and the ways popular media corrupt its meanings. He calls out the cultural tendencies that have necessitated the Black Lives Matter movement, focusing especially on the enigma of “compliance” with legal authority. With a deft allusion to the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” refrain, Anderson not only challenges the imperative to comply with racist police, he also asks how such compliance is possible when officers read even yielding, self-protective movements as aggression. In the background of one piece, a ghostly face watches in disbelief; in another, an antique sculpture lifts its arms as if to demonstrate the historical tenacity of the problem.

Photo by Tony Walsh

Photo by Tony Walsh

Beacon gives broad space to such problems, especially those whose persistence has become devastatingly plain since the last U. S. election. Emily Hanako Momohara’s photographs of the Manzanar, Minidoka, and Tule Lake Concentration Camps, where over 120,000 Japanese Americans underwent imprisonment during World War II, would be startling in any context. But they hold particular intensity now, almost eighty years later, as makeshift prisons for Latinx people range along the U.S.-Mexico border. Momohara’s photos feature desert landscapes at the site of the WWII camps, their arid expanses suggesting the severe conditions prisoners experienced there. The pictures also capture resonant, microhistorical details: infant headstones, barbed wire, rusted metal bedframes, weirdly pristine household fixtures. Here everyday intimacy cuts through the grand narratives of American history, collapsing spatial and temporal gaps between perceived distances. The aggregate photographs comprise a comment on national memory, parched yet struggling to survive. Momohara’s concrete steps to absent structures signal the consistency of repression. The art is “only relevant,” she observes, “if we do something with it.”

Photo courtesy of the artist

Along with Anderson’s attention to police violence, Momohara’s admonition gives a critical charge to much of the exhibit, lending an air of menace to otherwise innocuous objects. Cody Perkins’s parking lot lamppost, while it may first seem the most routine of beacons, becomes an oblique gesture toward collective alienation, synecdoche for the corporate superstore. And while his deteriorating basketball goal may have once promised diversion, it now verges on despair. At first encounter, a glowing cell phone tower constitutes the show’s most ecstatic statement, but alongside the other works it takes on a looming, imperious character. Elese Daniel underscores such ambivalence with ellipsis, asking the paradoxical question “How does a body move when it isn’t being watched?” She opens a virtual window on a garden, then walks without haste or self-consciousness through its greenery. Her movements match the space, languorous and at peace. Yet there remains a difference between the artist as character and the artist as designer, the one who cannot answer her own question and knows it full well. She is watching, after all, and so are we. It was always going to be that way, the installation implies. The apparent sanctuary does not evade but rather demonstrates the condition of surveillance.

Britni Bicknaver’s Cinema of Memory series produces similar effects as she assembles found photographs in lightboxes, equipping each station with head phones that transmit ambient music. The Polaroids and faded prints display a variety of scenes at once candid and nostalgic—people lying in the grass, playing volleyball, holding birthday parties, walking together at dusk. The shots might easily have been plucked from a 1970s family album, evoking the era in their physical format as well as the dress and décor they depict. Yet Bicknaver poses the problem of voyeurism at least as forcefully as Daniel. Again, the body cannot sustain its retreat from the gaze. The once familial is now public. As the installation laments the loss of the intimate and the singular, the soundscape becomes a dirge, scoring the sense of inevitable departure that Roland Barthes associates with snapshots in Camera Lucida. Children laugh and sing around birthday candles that are deadly still. Bicknaver lets us into the party, but we cannot claim to be invited.

Even the work’s access point triggers a certain dread, as the headphones present dangers that pre-COVID audiences rarely faced. Sharing the devices generates uneasiness despite the sanitizing stations available throughout the Weston. It also raises questions about the kind of art that asks to be touched even in a pandemic: How can we experience it without either ignoring its affordances or assuming unnecessary risks? Is posing that question itself a form of engagement? Amid the show’s frank statements about social inequality, estrangement, surveillance, mortality, and the traumatic recurrence of state-sanctioned violence, concerns about public health are at once apt and poignant. They recall beacons that have been deliberately ignored by heads of state, inflaming if not creating the crisis we now face. To recall Momohara’s words, those concerns remind us that the relevance of art, and of political expression more generally, depends on what we do with it. The work of the beacon requires our watchfulness.