The windowless white rooms that comprise the Carl Solway Gallery provide an austere setting for the LCD screen-based, chrome-armatured show Alan Rath: New Sculpture. The main gallery feels almost sparse; each piece is given a generous amount of space. At first glance, the robotic, high-tech pieces set against or mounted on the mostly bare, flood-lit walls seem like curious engineering prototypes that one might find displayed at a trade show. On closer inspection, details betray a sly, playful aesthetic that draws from pop culture, art history, and a sense of dystopian paranoia.

The Solway Gallery has a history with robots, going back to founder Carl’s partnership with Nam Jun Paik to create the artist’s renowned video monitor robots, such as the Metrobot that makes its home downtown in front of Cincinnati’s Contemporary Arts Center. Other artists the gallery has shown, such as Diane Landry, Ann Hamilton, and Jim Campbell, make use of quirky mechanics or high tech electronics as means of expression.

My interest in Rath’s work is the portrayal of human elements as content in his custom-designed electronic creations. Communication theorist-guru Marshall McLuhan’s said, “the content or time-clothing of any medium or culture is the preceding medium or culture, “ (Culture Is Our Business, 1970). Within the evolving culture of artificial intelligence (from SIRI to physical robots), and considering Rath’s medium of wires, screens, and circuit technology, I sought out implications for humanity in this emerging world. What kind of context for human presence does Rath provide in his sculptures? What is the fate of the hand, of touch, or at least something to reference a warmth, a pulse of life signaling a connection with the human behind the cool, glass screens, fabricated hardware, electronics, pixels, and algorithms? Is human culture becoming the content for a new, emerging AI culture? Rath’s work is an intriguing mix of such concerns, incorporating into the electronics and mechanics multiple images depicting natural and living forms, primarily human.

Disembodied human parts are ever present in this show. Eyes with expressions of indifference observe, peek, or conduct surveillance, as in Neo Watcher VI. Eyeris VIII is ironic and ominous. At once a visual reference to flowers and also to the opening of a lens, three tall, white, elegantly curved “stems” support oval screens that contain watchful eyes. Voyeur III continues the idea of surveillance, with an oversized binocular-looking device housing two large eyes, focused intently on something in the distance.

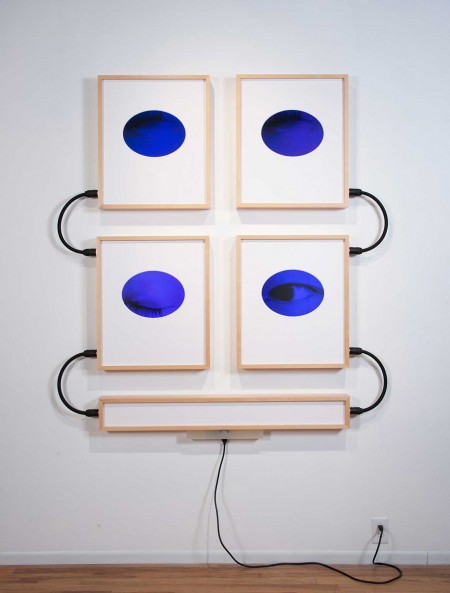

Walleye X made me smile. For all its technical materials (screen, metal housings, and plastic coated wire) the looping curve of the wire around its vertical silver armature delights as a fish jumping up out of the water. And yes, there is another eye in a small screen to form the head. Four Eyes is a symmetrical wall-mounted piece consisting of four wood frames connected by curved wires. Each frame houses an oval mat inside of which floats an eye. Instead of staring the viewer down, this piece greets viewers with closed eyes. Those most patient occasionally glimpse a quick opening and closing of an eye here and there.

Several of these works incorporate bold colors such as oranges, purples, greens and blues into their screens or as part of their armatures. This palette, along with wood frames and stands, lends a geniality to the otherwise sterile sculptural materials. The profiles of the pieces are clean and uncluttered, and the craft so pristine they seem manufactured.

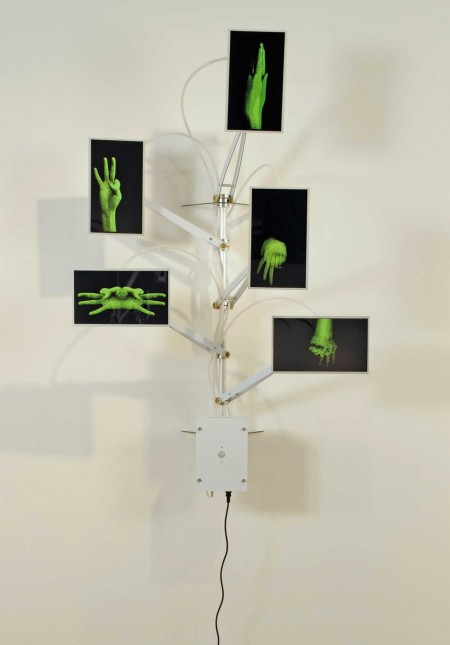

Some of the works use human elements, such as the hand and mouth, to transmit codes of meaning, codes we may or may not comprehend, languages we can or cannot decipher. In Six O’Clock, Rath arranges five small screens on an armature that uses images of hands to represent aspects of a clock, from movement of clock “hands” to the swing of a pendulum. Moving hands indicate time codes by signaling numbers.

In Bostock, several small screens contain images of hands that flash sign language alphabet letters. The screens are arranged on an armature and form a kind of “stick figure” with a double set of outstretched arms. The signed letters spell out all of the lyrics to the 1972 Jethro Tull album “Thick As A Brick”, a concept album that featured the tale of a fictional character named Gerald Bostock. In this layered work lies an entire human-fabricated character built into a human-fabricated humanoid figure. Codes of communication shift from sign language, silently spelling lyrics, to their translation into written language, which in turn implies spoken language as song.

In Read My Lips, what appear to be female lips repeat a phrase that the viewer is unable to hear. The message emanating from the purple mouth seems to be more about calm precision than urgency, as if encouraging the viewer to try to decipher its meaning.

There is, however, a sense of urgency in the sculpture Running Man On Chinese Stand II, an urgency to escape. I am reminded of Dustin Hoffman’s character in the 1976 film “Marathon Man”, where Hoffman’s measured pace aids an endurance that will eventually lead him to freedom from danger. The piece also recalls Eadweard Muybridge’s photographs of human movement from his 1877 Animal Locomotion series. The running man in this sculpture is a technically rendered full-figure profile on a small screen contained in a bell jar, a terrarium, a “Chinese Stand” that literally places mankind inside an antique-looking piece of decorative display furniture. Here we see human as content, artifact, a nostalgic object from a preceding culture, trying to run from such a fate.

The work that conveyed the most palpable sentiment of humanity to me, ironically, did not incorporate any human element at all. In Unknowable, a circle of long feathers is mounted onto a chrome armature, their long, sweeping ends projecting out from the center. An algorithm rotates and lifts the feathers, individually and together, creating a kind of gestural dance. It is the fluidity of gesture, and the curving of the soft feathers, that differentiates this piece. In all of the other works, the reference to life, to touch, to energy, is mediated by pixels. In effect, tactile imagination is most often left at a distance, with only the cool, smooth touch of the screen. The materials and textures of life, like skin, like feathers, evoke a visceral response that the digital cannot approach. And yet it is the algorithm that animates the dance. Rath’s work presents these counterpoints of human and technological in a subtle way. Beyond the obvious, ominous references to surveillance culture, he exposes, sometimes with humor, the inevitability of confluence of human and technological by juxtaposing access to the flesh, a hand or a mouth, always behind a screen; presenting apathetic, pixelated eyes and fleeing figures in warm wood frames; and making impassioned lyrical gestures of wires and hardware.

–Susan Byrnes