1: “Refresh (zine)” by Kristin Lucas, 7 stacks of 8.5×11” sheets of paper, stapler.

In 2007, Kristin Lucas began her ongoing “Refresh” series, in which she decides to legally change her name. But, it’s only a “refresh,” in the same way one would refresh a page on an internet browser: she was Kristin Sue Lucas, and she became Kristin Sue Lucas.

The court transcripts are part of the series, and can be found on her website. The documents have been read aloud at other venues, but I consumed selections as a deconstructed zine at DiverseWorks’ group exhibition, “What Shall We Do Next?”, up through March 19. There’s something deliciously bureaucratic about the multiple stacks of paper and stapler presented to gallery-goers, like the forms she no doubt had to fill out in order to accomplish the refresh—which she did, with only minor delays from the perplexed judge.

The packet not only includes the court transcripts and official forms, but emails warning her friends that she may not be the same: “In the event that I can no longer find myself after the refresh, please send a Search Party.” User-interface terms like “search,” “memory” and “content” litter these messages; her friends’ thoughtful, kind replies—emails, of course—treat the refresh as any other momentous life change.

Lucas’ piece places identity in the hands of two overarching cultures: our societal framework, and the home we have in technology. First, she frames her new beginning as a “refresh,” explicitly referring to refreshing an internet browser page. Then, instead of relying on metaphor, she turns to the objective, blind eyes of the law to legitimize her change. She must take a physical action, interact with real people—a different experience than hitting a button on the internet.

Despite preparing a statement for court, Lucas falters a bit on the stand while explaining her reasoning. As she tells the judge in the official court transcripts, “I should have brought a philosopher.”

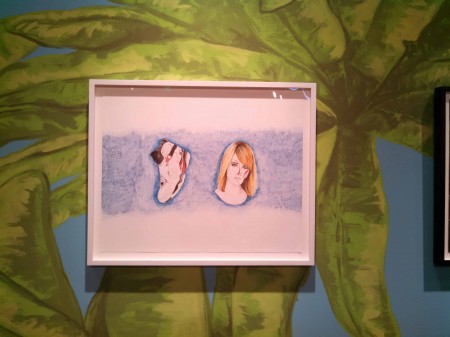

2: “Eat Garlic” by Danielle Dean, mixed media on paper

Lucas worries the judge will dismiss the case as foolish narcissism, a ploy to waste everyone’s time. In short, she is not in the right place. I felt a similar sensation when I attended what I thought would be a curator talk about “Where Shall We Go From Here?” at the University of Houston (UH). The event was actually the first of a new series in a cozy classroom, bringing together art historians, philosophers and writers from and beyond campus (professors, researchers and students alike) to explore the intersections and meanings between media—a wonderful idea for which I was not prepared, despite working for the University and earning an MFA in poetry elsewhere. I swear that everyone had a pre-assigned handout I seemed to be missing. Was this an academic lock-in that was only publicized online to fill the gallery’s “outreach” quota?

It didn’t matter; I’m sure I would have been happily offered one of the banh-mi sandwiches at the front of the room if I’d had courage enough to approach. The whole discussion was a hot bath of intelligence and theory, and I was happy to let it pass over me, scribbling down arresting phrases. Plus, Danielle Dean, one of the artists from the exhibit, was present to offer her point of view pertaining to her work. DiverseWorks’ curator, Rachel Cook, organized this particular gathering, which is probably what confused me. Leading the discussion were Christoph Cox and Jenny Jaskey, two of the editors of “Realism Materialism Art,” a new anthology that includes “a diverse selection of new realist and materialist philosophies and examines their ramifications on the arts.” Here’s the part where I, like Lucas, needed a philosopher, which is evident from this sampling of notes:

The questionable figure in art is the figure of the human; when do we not belong in it?

Art is an effect of linguistic circumstance.

How does the world differ if we think of objects as not being for us? But, objects being “for us” is the history of the world.

“Art” is situational process to many artists. Viewer participation is meaningless. They think, I don’t want to author things. I want to set things in motion.

Our institutional frame is capitalism. Our voracious art market changes art’s intention.

Consider Kant’s objectivism: that everything must be generic for genuine discourse to take place. Our societal condition cannot be taken into account when considering art.

Although the participants in the discussion made clear that they did not necessarily endorse Kant’s view (fully, anyway), it makes sense that this is when Danielle Dean would speak up. “All that falls apart,” she said, “when you consider the constructs of race and gender.” Indeed, Dean’s work in the exhibition is rooted in the commercialization and inequality that pervades our world, and challenges socially constructed narratives like race, class and gender. It clearly has an intention—it’s not a “situational process” situation as noted above.

Take “Eat Garlic,” for example. Part of her exploration of Nike’s exploitation of workers and women, the small painting depicts a sneaker and a woman’s head, the sneaker’s stitching and logo transposed onto her face. Dean’s work is a prominent physical presence at the exhibit, with the feet-high structures of “True Red Ruin” occupying one corner of the gallery and “True Red,” an animation of objects and people transforming into each other, playing on loop in another.

The animation embodies another one of Dean’s statements during the discussion about whether objects have their own lives. She said, “But, humans are also objects. How we live and see an object other than us fosters inequality. If we see each other as objects, maybe it will make us see each other in a fairer light.”

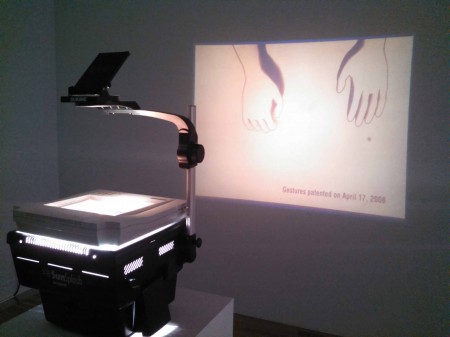

3: “What Shall We Do Next?” by Julien Prévieux, animation.

Considering this exhibit, despite its unsentimental, abstract methods, I find myself falling into a sort of sentimental trap: seeing a piece of resonant art makes a “refresh” possible. In the “art” dimension, friends unironically accept the conflation of name change with identity change (even if the name stays the same) and drawing subjects that take on the physical aspects of the objects that play a part in their own exploitation. We go there for a moment, and come back changed.

It reminds me of the theater warm-up exercise in which group walks around the room moving left arm with left leg and right arm with right leg, against natural motion. An absurd-feeling physical motion is helpful (necessary?) in removing oneself from the everyday, and preparing for fresh, creative experience.

After the philosophical discussion at UH, though, it’s interesting to think how art can still refresh if it is commodified. Is art that has this refreshing effect not commodified, then? Is commodified art just another layer of pleasure or displeasure on top of our already existing viewpoints? Is it not art if it doesn’t lift us out of our everyday motion?

At first blush, Julien Prévieux’s animation, whose title also serves as the exhibit title, effectively blazes the notion that we create new things while also critiquing capitalist quantification. Disembodied hands perform gestures alongside their copyright date. Copyrighting a physical gesture, free and performable by practically all, seems to be the bottom of the barrel in terms of commodification, and Prévieux engages immediately with that suggestion.

Knowing the animation’s background creates another layer: these actions are related to patents for the invention of new devices, filed between 2006 and 2011 with the United States Patent and Trademark Office. The operation of these machines requires actions that are specified and patented, even if the object does not exist yet. So, even if no one has invented a machine that would use these gestures, future machines that necessitate these actions must be created by the patent owner.

Even Kristin Lucas had to pay $320 to the Superior Court of California to “change” her name. The system(s) work, I guess. At least some galleries, like DiverseWorks, are free of charge, and bringing refreshing artists to Houston.