I married into a quilting family. One corner of our wedding quilt lists all the names of the women and men who helped piece it together before one aunt fed it to a nearly-room-sized robot, programmed to finish it off with polish and a custom, uninterrupted design. The family matriarch got a look at the machine before she passed away, marveled at it, then threatened the family to never put one of her quilts under “that thing.” I think of how well-made it is whenever I put it through the wash, gentle cycle and line drying being more of an act of reverence than worry. It’s sturdy.

Conceptual artist Anna Von Mertens hand stitches each of her works, although, as curator Jennifer Roberts noted in a Q&A, she could easily have the designs sent out to be completed by machine. “Measure,” at the Johnson-Kulukundis Family through January 19, features five quilts and one pencil drawing. If I had the gall to use an “art quilt” on a bed, I would never risk even a gentle cycle on these elegant handstitched wonders—not because I think them weak, but because the thought of the black background fading is painful. Her star trail on the pitch fabric canvas, represented by the calculated tentativeness of a dotted line, marks a void to be filled. Here, we fill it with one specific life.

Some background: Von Mertens entered the medium of textiles through quilts and poetic variants on moving blankets—quilts representing both as the known domestic landscape and unknown territories, she explains—displayed on “beds,” provoking a sense of intimacy in a gallery while turning viewer into intruder. But she has since moved to the wall, and the quilts and drawing on view at the Radcliffe Institute at Harvard through January 19, 2019, use her research at the Institute to take viewers into the darkest reaches of space—and more intimate quarters of one individual’s life and work.

That individual is one that Cambridge residents are growing more and more aware of, after nearly a century of relative obscurity: Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868-1921). Leavitt was one of a group of woman computers who used images from “the Great Refractor,” Harvard’s telescope with a 15-inch lens that was, from 1847 to 1867, the largest in the United States. Coincidentally, the local Flat Earth Theatre company produced “Silent Sky,” a play by Laura Gunderson in which Henrietta is the central character. The theater had the rights secured before they learned about “Hidden Figures,” the critically-acclaimed 2016 film about Katherine Coleman and other African-American computers at NASA in the 1960s. So, even if Henrietta Leavitt isn’t yet a household name, the female computers of the 20th century are at least finally gaining recognition.

Even disregarding this particular cultural moment, it’s difficult to imagine that Von Mertens would have chosen any other story, so tangible is her passion for Leavitt’s contributions and the thematic overlaps with her own artistic practice: small gestures, as in hand-stitching or smartly-kept ledgers; calculation; joining layers together to form a new, meaningful object. This exhibition fits neatly into the one room, but its thematic reach—and the time taken to execute the meticulous craftsmanship—is vast.

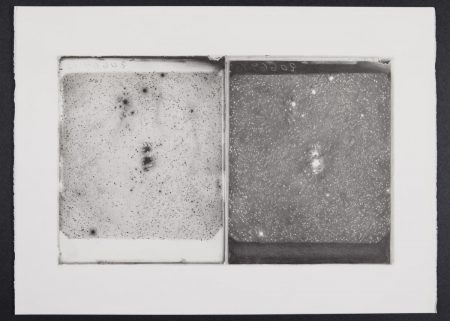

The concept of Henrietta’s legacy, and her calculations and labor that changed the field of astronomy and how we understand the sky, is central to most of the pieces in Von Mertens’ work in this exhibition. Very little is known about Leavitt’s life; she never married or had children. Her name came up in conversations about the Nobel Prize only after she had died from cancer. Her known legacy revolves around her labor on telescopic images manifested onto glass plates, their black and white values reversed like a photographic negative. Leavitt would layer these glass plates to calculate levels of brightness in the stars, ultimately leading to the creation of a “distance ladder” into the heavens.

One piece shown is a photo-realistic pencil drawing of two of the star plates that, Von Mertens reported, took longer to complete than the exhibition’s quilts. Here again we see how the smallest actions make an impact. The inverse print shows the hard pencil marks of the stars, while on the other side, the furred darkness of small pencil strokes become the farthest reaches of space, the stars a blank. It was while describing this work that Von Mertens said “it was a joy to pay attention” to every miniscule pencil stroke on these plates. Diplomatic, perhaps, but also a wonderful artist’s statement.

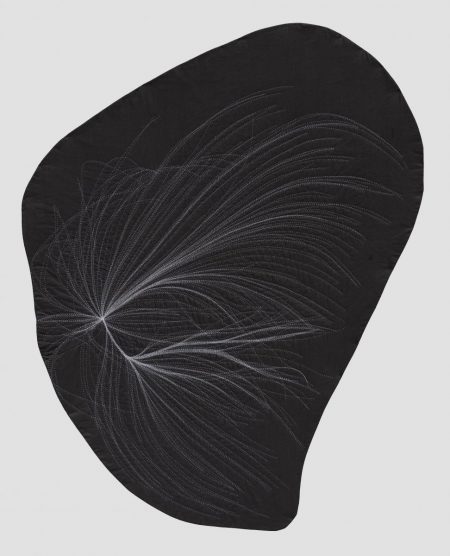

On another wall hangs three textile pieces in her “Shape/View” series—Von Mertens made them independently of the Leavitt materials in 2016 upon the discovery of new galaxy superclusters. These works depict the superclusters from different angles, although there’s no way of telling without the backstory. They complement the newer works effectively, each an irregular shape that’s almost torn from space. Each hand-stitch in these represents not a star, but a whole galaxy. The threads are white, not varying in brightness, each winding into clusters larger than the human mind can comprehend.

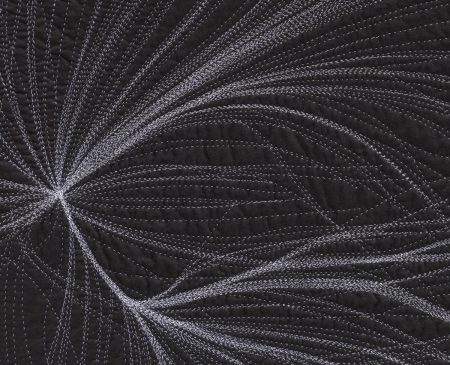

Placing the superclusters across from an encapsulation of Leavitt’s life—star maps of her birth and death days—takes the viewer on a journey of scale. These two quilts are the centerpiece of the exhibition, depicting the night sky on two historic dates: “The stars fading from view on the morning of Henrietta Leavitt’s birth, July 4, 1868, Lancaster, Massachusetts,” and “The stars returning into view on the evening of Henrietta Leavitt’s death, December 12, 1921, Cambridge, Massachusetts.” Von Mertens used software to calculate what the stars looked like on each date, using threads of varying grayscale to characterize each one based on brightness. Each stitch ripples the pitch black fabric just enough to effect texture at close range. The size of each piece, as well as the pitch background, are deliberate in their efforts to evoke a cinematic frame. The streaks of the stars bring motion to the forefront of our minds, as if we’re viewing a meteor shower instead of what would have been a still night, motion only captured over time—a loving, overdue mythology for a star tracker.

Von Mertens first created variants of these tender maps for “As the Stars Go By,” her 2006 exhibit depicting the night sky at the moments of tragic events throughout American history, including the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and September 11, 2001. It’s unfair that my heart dropped when I learned that she had created these maps before—it’s not fair, not when the messages are so different. From what I can tell, that show made viewers angle their vision upward during these history-altering events in a way that shows the sameness of each tragedy, both dulling and expanding the meaning of each one. This one seeks to bookend a singular life, whose passion was devoted to the stars themselves.

This preexistence dulls the impact of the exhibition from an incisive illustration to thoughtful tribute. Not a step down, but sideways, into the void of endless possibilities. Adding Henrietta’s lifespan to this style of interpretation doesn’t evoke the same gut punch—while the pieces are still beautiful in their meaning and level of skill, Von Mertens is now only one step away from a patron saying “now do my birthday” and hiring a machine to start monetizing her concept more efficiently.

But even if that does come to pass—and after hearing Von Mertens’ opening lecture, rife with earnestness and poetic stitching, I highly doubt it will—who cares? I wish my robot-wielding-aunt-in-law would sell her beautiful creations online. Besides—you can buy a star chart online, so why not drape your walls and bed in fine art that shows the same thing? I only present this view to mark the tonal state of this largely academic exhibition. It was born of Harvard research, and proliferates into an intriguing series of cross-disciplinary events. Von Mertens is not kicking down a specific door, just opening up several windows to illuminate a notable woman’s life. Considering how unassumingly Leavitt kicked down the door to modern astronomy, perhaps simply reveling in that accomplishment is most appropriate.

The Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum is hosting a multifaceted fiber exhibition this season, but it is a joy to pay attention to one individual’s life in a small gallery, accompanied by their fantastic 50-page full-color catalog. The meticulousness of Von Mertens’ work mirrors Henrietta’s, in a way—but at the end of it, we have not the means to measure the universe, but one conceptual unit of measurement for an individual’s life. Wrap yourself in this show.