I can’t decide if I should leap for joy or feel cheated by the art world when I discover yet another marvelous woman artist who has not received appropriate mainstream recognition. Here’s Kay WalkingStick, now in her eighties and thriving in her studio practice, who has had a vibrant career with early New York accolades. She deployed innovations in paint processes that made for arresting paintings by the 1980’s when she grew into her most contemporary style. She brilliantly weds contemporary ideas in her paintings, prints and drawings with her conscious act of incorporating Native American philosophy and visual identifiers.

The exhibition comes to the Dayton Art Institute, its third stop, after opening at the Smithsonian’s American Indian Museum in Washington, DC to September 2016, then at the Heard Museum in Phoenix, Arizona. The traveling retrospective exhibition is co-curated by NMAI curator Kathleen Ash-Milby (Navajo) and associate director David W. Penney, in close collaboration with the artist. Their substantial catalogue, the first of its kind, also features writings by legendary critic Lucy Lippard. There are three more museum stops after Dayton.

There are a number of contemporary Native American male artists who achieved fame and/or whose paintings, sculptures and prints became highly collected in the mid-20th century. Fritz Scholder is one of the most famous, followed by R. C. Gorman. They were folded into the mainstream while maintaining their native heritage identity. While they didn’t enjoy the vaulted fame of Robert Rauchenberg, Jasper Johns, Richard Diebenkorn, and a raft of other white male painters, nonetheless they did get press, fame and sales. They may have been pegged as contemporary Native American artists, just as David Parks was pegged as a Bay Area artist, but they had recognition. No wonder the Guerrilla Girls were created! Other than Maria of the Pueblos, a brilliant 20th century potter, who else among native women artists can we easily name? Jaune Quick-To-See miraculously made it into the mainstream, but her name doesn’t pop into our art heads readily and I feel her powerful fine art prints had a real political punch which helped her achieve more fame than WalkingStick has achieved, given that they are close in age.

So let’s look at WalkingStick’s paintings and see what she has done. The exhibition breaks into chronological parts, starting with “The Sensual Body: Early 1970s.” Here from the start it is evident she loves process, in this case hard-edge, flat paintings which were of the moment in NYC. She could soak this up as the city was not far from her home in New Jersey. “Me and My Neon Box” depicts exactly what the slang suggests and it is bold and funny. The Smithsonian states: “The nudes (most of them self-portraits) reflect the era’s newly liberated female sexuality and WalkingStick’s explorations of her artistic identity as a female painter in a male-dominated profession.”

Graduate school and its effects brought more intense exploration, featured in the section “Material and Meaning: 1974–85,” but I found her best work started with “Two Views: Diptychs.” The Smithsonian described that “In the mid-1980s, WalkingStick began to combine images of landscapes inspired by her home and travels with abstractions in what would become her signature format: two square, side-by-side paintings called diptychs. The diptych helped her express spiritual themes. Painted with her hands, the landscapes signified what she called “snapshot’ memories, while the abstract panels represented deeper, “mythic” memory. When combined, the two panels express different but complementary kinds of knowledge: external sensory perception of the material world on one side, and internal spiritual comprehension on the other.”

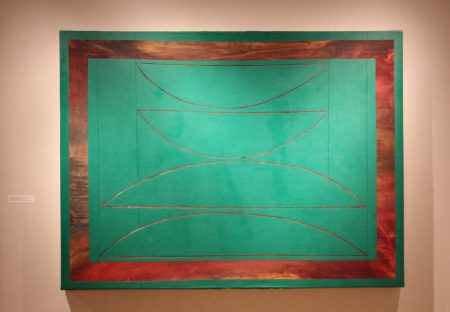

With her diptychs, WalkingStick ramped up her processes, using prevailing cutting-edge techniques with acrylics and making them her own. For example, she soaked the unprimed canvas with thin stains of colors, then masked off areas so these delicate veiled washes would be preserved while she aggressively laid on thick swaths of bold, opaque acrylic paint and wax. The resulting diptychs are extremely sensual and aggressive. She pushes acrylics around to her will and vision at a time when acrylics were not being handled this way. Other artists were enamored with the flatness of acrylics, whereas WalkingStick troweled the paint on more like the AbEx painters had done. She marries physicality to her clarity of vision. Toward that end, her Chief Joseph Series is a haunting meditation on a heroic Indian hero which she commemorated with a large wall installation of many small abstract paintings. She is at her best with symbolic abstraction.

The section features paintings influenced by her summers teaching in Cornell University’s Rome program is called “Italian Romance.” WalkingStick added gold leaf to her studio enterprise. These art works are magical, less political, more figural and lyrical – as one might imagine that studying an ancient culture would naturally lead in this direction. WalkingStick tapped more into universal rather than Native American themes.

Equal to the section of the exhibition showing her powerful abstractions and diptychs, is the final area, “Landscape: The Power of Native Place.” Here too, Walkingstick really shows her ability to meld her Native American symbolist ideas with somewhat abstracted landscape vistas. The relationship between Native people and the land is obvious, not only philosophically (no one owns Mother Earth) but also in the tragedy of losing the use of the land to the white European invaders. Her depiction of the Trail of Tears is powerful, but very delicately handled, with small silouettes of Indians making an arduous trek in the landscape. Her love of landscape forms is evident and they are enriched by carefully coded Indian symbols and silouettes.

Kay WalkingStick, born in 1935, had a Scotch-Irish mother and a Cherokee father. Although her father was quickly absent from the family, her mother raised her to be proud of her Native American heritage. WalkingStick received her Bachelor of Fine Arts and Master of Fine Arts from Pratt Institute, New York (supported by a Danforth Foundation Graduate Fellowship for Women.) Her first solo exhibition in New York City was in 1969, followed by participation in numerous exhibitions in the New York area during the 1970s. She has since exhibited her work in more than 30 solo exhibitions, numerous group exhibitions nationally and internationally, including “The Decade Show: Frameworks of Identity in the 1980s” (1990) and “Land, Spirit, Power: First Nations at the National Gallery of Canada” (1992). She was the first Native American artist to appear in H.W. Janson’s “History of Art” (fifth edition, 1995). WalkingStick’s work is represented in the collections of several museums, including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian, the National Gallery of Canada and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. She has received many awards, including grants from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, the Joan Mitchell Foundation, The National Endowment for the Arts and the Eiteljorg Fellowship for Native American Fine Art. She is a faculty emerita at Cornell University where she was a professor in the Department of Art, retiring in 2005.

The exhibition opened February 11, 2017 and continues until May 7 2017. It includes a short and very informative video, Kay WalkingStick: An American Artist.The Dayton Art Institute, 456 Belmonte Park North, Dayton Ohio 45405 937-223-4ART (4278)

Cynthia M. Kukla is an artist and professor emerita of art living in Northern Kentucky

Addendum: Painter Kerry James Marshall received the College Art Association 2017 Artist Award for Distinguished Body of Work. See my 2016 review of his exhibition in Aeqai:

https://aeqai.org/2016/05/letter-from-chicago-kerry-james-marshall-mastry-opens-april-23-and-runs-through-september-25-2016-at-the-museum-of-contemporary-art-chicago/