Being unfamiliar with Kirk Mangus’s (1952-2013) work, seeing his exhibition at Carl Solway Gallery of ceramic sculpture and drawings, spanning four decades, was overwhelming. I can’t describe the work or its impact better than Douglas Max Utter did in his review of Mangus’s 2014 retrospective, “Things Love,” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Cleveland: “Any gallery full of objects made by the late Ohio ceramicist Kirk Mangus is likely to be a sort of rodeo, a roundup of beautifully rambunctious, animalistic ceramic explorations that might need a lasso or a treat, just to keep still.”1

Head of the ceramics department at Kent State University from 1985 to 2013, Mangus received a B. A. in 1975 from the Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, where he studied with Jun Kaneko, and an M. F. A. from Washington State University, Pullman, in 1979. The neo-primitif and cartoon-y painting styles of his mentors there, the painter Gaylen Hansen and Patrick Siler who painted on ceramics, influenced Mangus’s own style.2

Both of Mangus’s parents, Chick and Nizza, were ceramists and taught in the local public schools. (Chick studied with Toshiko Takaezu at the Cleveland Institute of Art, and she became a friend.) The family lived on a farm in Sharon, PA, with a studio in the barn and a couple of kilns. Mangus eschewed following them “because of all the people who knew my dad. I thought I would always be second fiddle or, worse, just ‘the kid.’ Sculpture or painting would have been fine occupations. So I drew everything around me; I considered it the road to my independence. Of course, this is not the way things worked out.”3

Mangus spent three summers at North Carolina’s Penland School of Crafts (1970-1972), and it was there he began to focus on clay, learning how to throw pots. When he returned to RISD for his sophomore year, he took sculpture, ceramics, and figure-drawing classes. He eventually “dropped traditional sculpture and became a potter,” seeing “pottery as the transformation of mud, through fire, into personal, expressive objects that can be used for food, displaying things, and decorating the environment.”4

As for the differences between functional ware and fine art – the question all artists who work with traditional craft materials are asked — Mangus replied, “My work is useful to look at.”5

It’s easy to identify Mangus’s inspirations and influences. In no particular order, here are some: Kaneko, Ron Nagel, Peter Voulkos, Viola Frey, Michael Lucero, Philip Guston, Jim Nutt, R. Crumb, Maurice Sendak, Dick Tracy comics, Pre-Columbian ceramics, blue-and-white Chinese export ware, Hindu gods, sumi painting, ziggurats (Aztec, Mayan, and Mesopotamian), Art Brut, Greek pottery, the so-called brown pots of the 1960s clay movement, “Bad Painting,” northern India manuscripts, and Buddhist and Mayan tropes.

Eva Kwong, Mangus’s widow, adds Warren MacKenzie, Antonio Tapies, Jean Dubuffet, outsider art, Abstract Expressionism, process art, Asian art and calligraphy, Zen and Japanese culture, jazz pianists, and Chinese Song carved porcelain. The one thing Mangus totally rejected was Minimalism, the prevailing style of time.

Despite all of these influences, Mangus’s work never looks derivative – or maybe because of the multiplicity, it can’t.

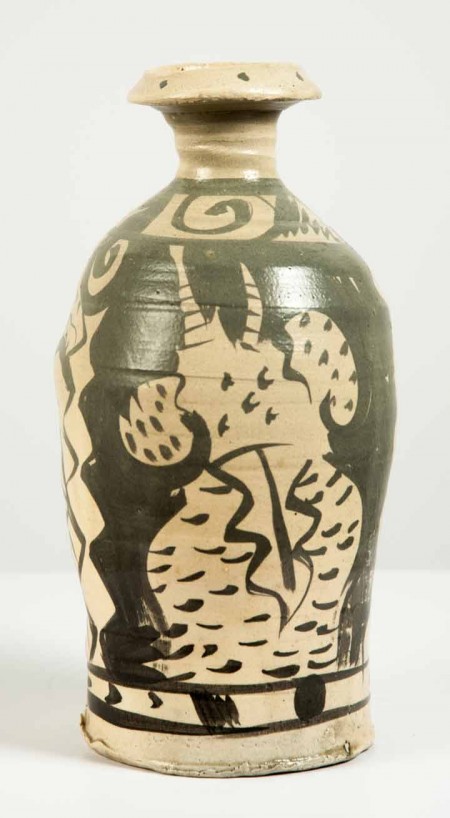

I’ll suggest two things that define Mangus’s style. The first was his use of traditional functional objects as the starting point for his energetic vessels. You can see references to ancient Greek amphoras and kraters, bambolas (tanks or cylinders), jars, cups, bottles, pitchers, and bowls, but he never violated them as Peter Voulkos had.

Mangus also made make some purely sculptural forms, notably the “Femmes” of the mid-1980s that might be likened to Willem de Kooning’s “Women.” The bodies of Mangus’s ladies aren’t terribly feminine. Phallic is more like it, as they resemble Kaneko’s “Dangos” or ancient menhirs. The “Femmes” have miniscule heads, and there are two knobby additions on either side of the bodies that may be oddly positioned breasts or vestigial arms. However, there is a large vertical slit that is unmistakably a vagina. But these sculptures are the exception to the rule.

The second characteristic is how Mangus uses the surfaces of his ceramics as a support for his incised and painted drawings. Steven Litt in a review of Mangus’s show at MOCA Cleveland in 2014, wrote, “Mangus was a devoted draftsman who loved incising linear images and patterns in his ceramics, often by carving deep lines that created an alligator-skin surface.”6

When Mangus was a college student, he “drew the figure only as an exercise and never on pots. This was based on my disdain for academic practice being transposed onto pottery, as well as on my considerable insecurity,” he wrote. “I decorated my pots (such as the 1977-1979 “Flintstone Cups” in this exhibition) with splashes of slip and insect images that were forms of personification and decoration. It took more than five years before I gained the confidence to illustrate my pots with the figure and to build life-size statues.”7

Mangus’s late 1980s Snake Amphora (25” x 12” x 9”) illustrates both of these characteristics. He carved into the surface of the recognizable classical form and used decorative additions, some made with sprig or press molds. A bunch of grapes is among the applied elements; they reference the amphora’s wine-storing function. One of his vocabulary of motifs, which tend to be personal references, is the martini glass incised into the surface. It was his parents’ cocktail of choice.

Mangus’s disjointed narrative continues around the Snake Amphora as it would in Greek pottery. On the back there’s a cat woman, his common depiction of his wife. Snakes slither around the body of the vessel and form its handles. These serpents could refer to the Biblical Eve, especially since his wife’s name is Eva.

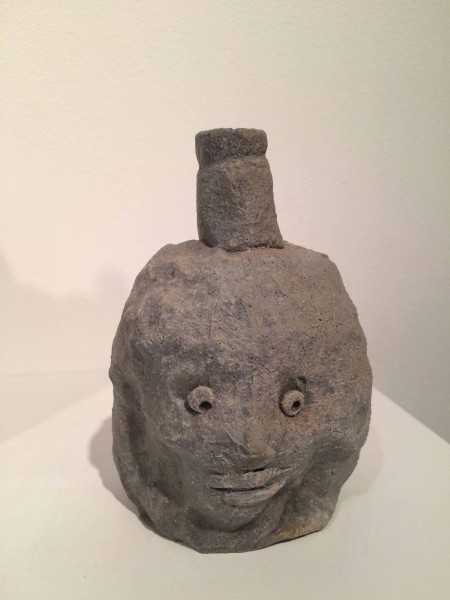

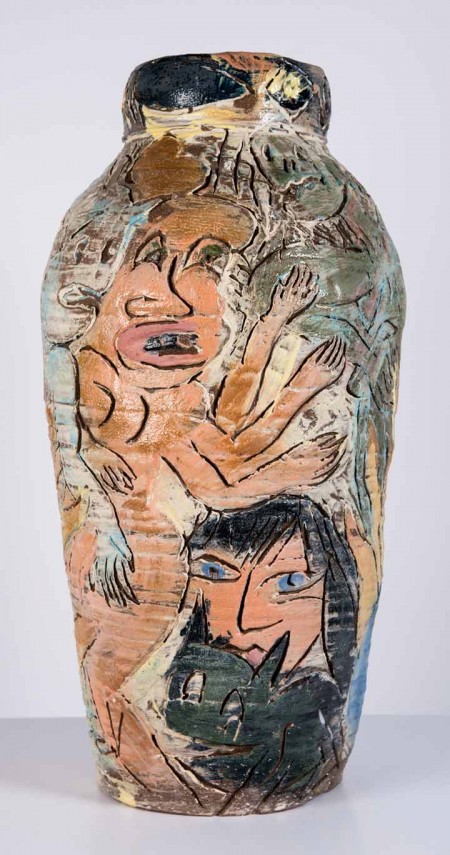

Some of the most arresting ceramic pieces in the exhibition are his bulbous “Face Vases,” which he made throughout his career. There are examples here from 1983, 2008, and 2011. They recall the portraiture pottery of the Moche culture, which thrived from 200 to 700 B. C. on the north coast of Peru.

Two of my favorites are the stoneware Girl with Dog Mask (aka Dora) (18” x 14” x 14”) and Tiger (aka Tiger Lily), (16.5” x 13.75” x 14.4”), both 2008. He’s carved into the surfaces to create dimensional masks and added clay attachments for ears and noses. He used underglazes to paint the features of the faces, giving them blue eyes and red lips.

Dora wears a dog-face mask, which covers the top half of her face, but does not hide her Mona-Lisa-like smile. It could be a tribal mask that I can imagine being used in some sort of benign ceremony.

Tiger Lily wears a forced smile, revealing an intimidating set of choppers, but the black mask evokes the Lone Ranger or Zorro, making her one of the good gals – I think.

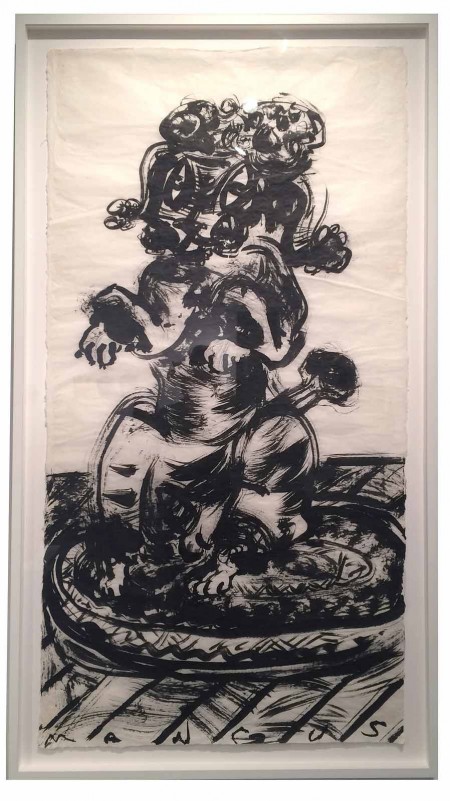

The drawings in the exhibition are independent works, not sketches for the clay works. Litt saw Mangus’s drawings as functioning “like the gas jet at a steel mill – a way to burn off excess energy.”8 Utter describes them as “unapologetically clumsy, gorgeous physical objects imbued with a sense of life and humor.9

Mangus viewed his drawings as a “sideline. I recorded ideas and sketched people doing everyday things. It was not until 1978 that I discovered drawings as objects. The activity became a passion again,”10 and a daily activity.

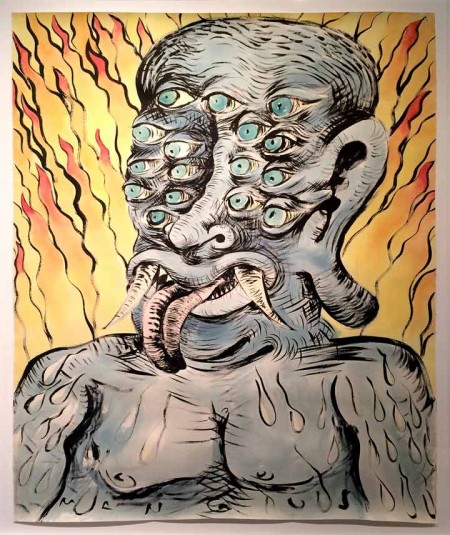

There is an interesting relationship between the Multi-Eyed Guardian Jar (stoneware, colored slips, sgraffito drawing, salt-glazed, 29.5” x 13” x 13”) and the 1989 Multi-Eyed Guardian (64.5” x 52.5”), a watercolor-on-handmade paper drawing. (Mangus liked handmade paper because it had “personality; it fights with you.”11)

The blue-skinned Multi-Eyed Guardian, with a tinge of Philip Guston’s late drawings, is “a fanged, sweating, humanoid monster sticking out his long black tongue as he stands in front of a wall of fire. Appealing and goofy rather than sinister, the guardian seems like a creature that has popped out of a child’s cartoon,” according to Litt.12

As comic as the guardian might be, he is well equipped for his task. A plethora of wide-open eyes extend from his forehead to the end of his crooked nose to make sure he misses nothing. His tusk-like fangs and shark-like teeth are fierce, and that tongue is ready to lap up anything left of anything or anyone that would challenge him; I definitely don’t see it licking an ice cream cone.

On the jar, the guardian has fewer eyes, and keeps his tongue to himself. To me he’s less jokey and more Kabuki. On the three-dimensional object, Mangus has another “canvas.” On the reverse a rather flabby nude human figure is supplied with multiple arms, perhaps suggesting an out-of-shape Shiva. A female figure, which I’ll take as Eva, seems to hold a feline in the front of her face. The cat’s head could be seen as a building; with ogival-eyes and steeple-like ears, it can be read as a church. If you see it that way, those flames become rather hellish.

In a long email from Kwong, originally sent to Rose Bouthillier, who organized “Kirk Mangus: Things Love,” and the Cleveland art dealer William Busta, author of the catalog essay, and shared with Michael Solway, his widow talks eloquently about Mangus, about his inspirations, his techniques, and the correlation of drawing and ceramics. She concludes with what I’d call the perfect summary of Mangus’s oeuvre: “Every thing connects back.”

–Karen S. Chambers

1 Utter, Douglas Max. “Kirk Mangus/Things Love,” arthopper.org, December 13, 2014.

2 Glen R. Brown in a December 2008 article in Ceramics Monthly, wrote, “It should be emphasized that Mangus’s style is a style in the very best sense: which is to say that the look of his work is fundamentally tied to the content that he investigates rather than merely applied superficially as a means of distinguishing his pieces from the products of anyone else.” “Kirk Mangus: The Crystalline Moment,” Ceramics Monthly, December 2008, p. 35.

3 Mangus, Kirk, “Cross Currents,” Studio Potter, nd.

4 Ibid.

5 Bouthillier, Rosa. “Things Love,” Things Love, Museum of Contemporary Art, Cleveland, 2014, p. 14.

6 Litt, Steven, “MOCA Cleveland celebrates the weird, wild, wonderful world of the late Kirk Mangus,” The Plain Dealer, December 4, 2014.

7 Mangus, op. cit.

8 Litt, op cit.

9 Mangus, op. cit.

10 Ibid.

11 Litt, op. cit.

12 July 28, 2014, email from Eva Kwong, originally to Rose Bouthillier and William Busta, and shared with Michael Solway.