When we encounter a portrait of the artist in her studio, a readymade that calls into question its own selection and display, or a time-lapse series that documents change in specific structures and locations, we receive an invitation to reflect on processes of artistic invention and performance. In most any exhibition, we can find works that concentrate on their own making, or, more broadly, the act of creation. The genre has many variations, one of which concentrates on how artists handle frustrations and setbacks. Manifest Gallery’s Unfinished/Accidents: Art about Serendipity gives that approach focus by exhibiting pieces where irresolution constitutes an expressive strength, and where initial miscues and outright blunders become motors for imagination.

The accidents, in particular, call into question the agencies at work in artistic production. Epistemologies dedicated to creative autonomy might emphasize the maker’s flexibility and daring, applauding the rescue of meaning from apparent disaster. As the gallery notes suggest, the mishap that seems at first to ruin a piece might instead “make it brilliant.” But those notes also harbor a more sophisticated, materialist idea of production that credits objects, unplanned events, and deceptively inert environments with participatory qualities. From that perspective, the ecology or surround works through the artist, not merely frustrating the desire for control but refusing its necessity. Such refusals may not always be welcome, and, as the curator remarks, they may even produce “fits of cussing.” But once the artist reconciles with the interruption, or better yet, the forceful assertion of what was there all along, the relinquishing of authority can produce dazzling results. The juried show at Manifest spotlights eighteen of those results from a competition that drew over two hundred entries. And while most of the winning pieces disguise whether they represent unfinished processes, accidental discoveries, or both, they all signal the emotional and aesthetic value of letting go.

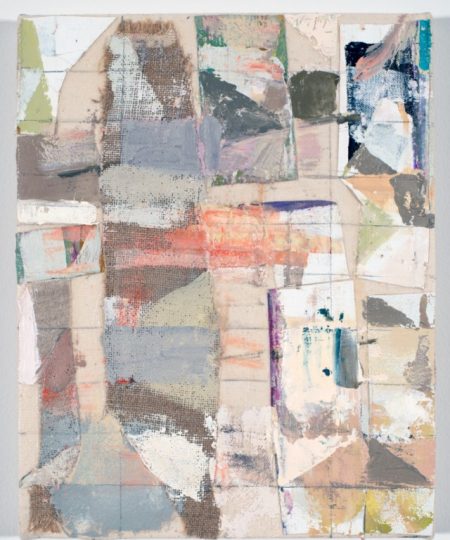

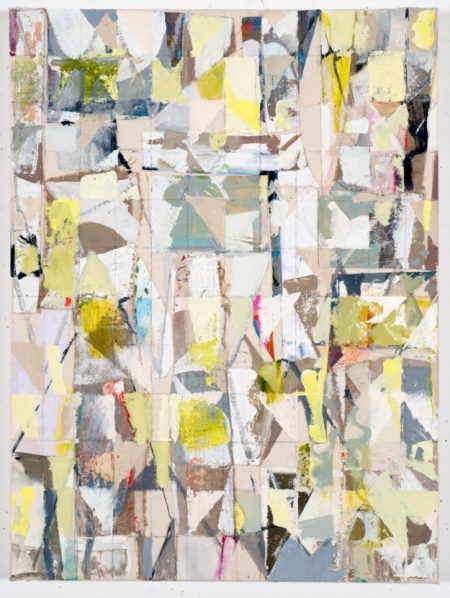

The pleasure of release becomes clear in a pair of untitled works by Sam King, each of which mixes a range of colored linens and paints on grid-lined canvas. The persistence of frame-grids behind the brushstrokes accentuates the unfinished quality of the piece, as do the scatter of loose threads and the curling of untrimmed fabric. Although one work is visually warmer and more frenetic than the other, both feature color patterns that create the sense of uncertain, playful motion. Both of them allude to ordered geometries while also subverting them, hinting at a tidy network structure and yet spilling over boundaries in most every area of the visual field. But as soon as the spectacle of disarrangement makes its takeover bid, Cubist signals of landscapes and architectural forms draw our attention back to the figural. If that dialectic was inspired by an accident, the mishap has so thoroughly integrated itself into the image as to be indistinguishable.

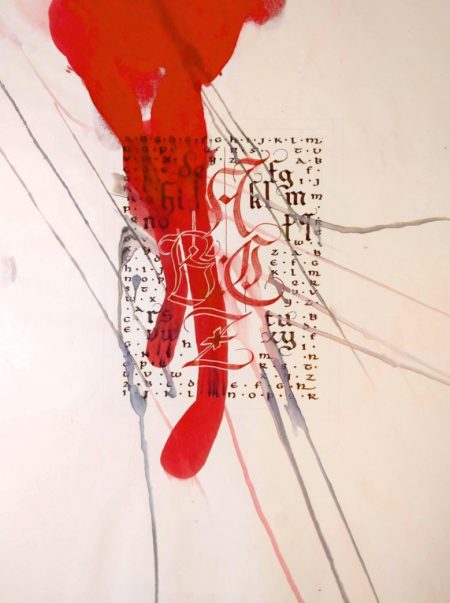

Sharon Reeber’s Rubric, on the other hand, spotlights the anomaly rather than integrating it, converting an ink spill into something violent and alive. At the center of the work there hangs a calligraphic alphabet, repeating in different sizes and arrangements. A cloud of red ink stretches downward from the top left corner of the page, interrupting and threatening to consume the elegant script. Smaller but more piercing streaks crisscross the picture plane: the lines an artist might make to test the flow of ink become the art itself. As with King’s efforts, Rubric establishes a productive tension between right-angled solemnity and bold leakage. And like King, Reeber shows as much interest in the physicality of her media as any mimetic or conceptual form they might yield.

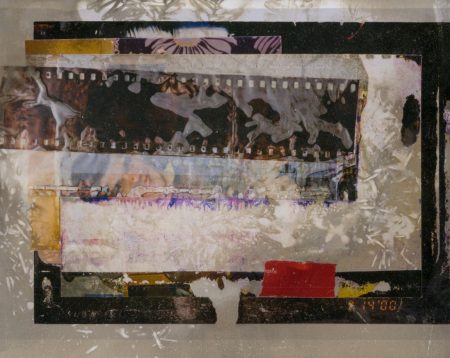

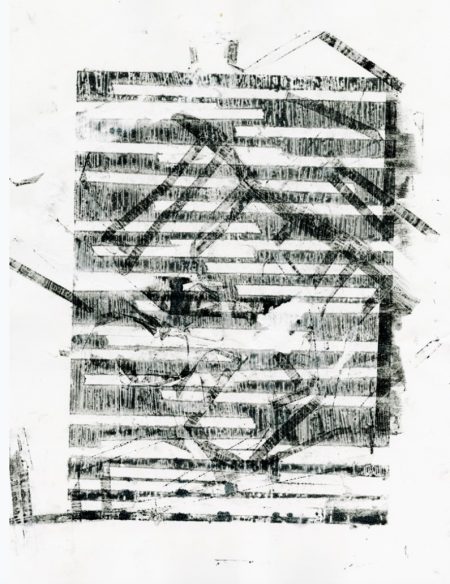

Sometimes those media seem to express a will of their own, as when a spill becomes a work’s richest detail, or the process of decomposition brings unanticipated textures and tones. The curator depicts those moments in whimsical terms, evoking “genii of chance” who “abide in various corners of the studio awaiting their moment to help.” In more prosaic fashion, we might substitute the idea of creative ecologies for the mystic persona of chance, focusing on how composing environments generally contribute to design processes in ways that exceed the logic of intention. Deborah Orloff’s Damaged Negative on Aluminum underscores that situation by focusing on media throwing their own purposes into question, doing something other than what technical procedure and artistic convention intend for them. Intricate visual rhythms arise from film coming into contact with harmful light and foreign substances. Rainbows of corrosion engage with ghostly bodies in snapshots and still frames, borders and layers multiplying to create a palimpsest of rebellious signals. The work takes issue with family photo albums and linear cinema as well as the imaginative limits of portrait and narrative, extending its critique to the very idea of representation. It makes the case in rough-and-ready ways: lacerations, bubbles, wrinkles, slapdash sutures where we might expect clean splices. All suggest a “damaged negative,” yet the damage acquires an ironic cast given the virtuosic intensity of the piece, its contrasts of monochrome and flame.

Where some of the show’s entries turn damage to their advantage, others unsettle the very idea of damage while destabilizing ideas of polish and completeness. How do we know, they seem to ask, when a work is done? Artists regularly face the problem of stopping too soon, leaving a piece underdeveloped or its queries unresolved. By contrast, they also risk “overworking” a piece, closing off ambiguities and suppressing what the curator calls “the living nature of the work at hand.” Melissa Gwyn confronts those difficulties in Trio Disorder by superimposing form upon form, texture upon texture. In varied sections of the picture plane, pastel oils appear to congeal or curdle, rising off the surface to create a fickle depth. There is no easy way to distinguish registers of proximity: the color clots that lift off the panel double as islands that float into the distance. Swirling purple and green lines cycle frantically through the center of the painting, but then, after continued consideration, they stall in their amoeba-like environs like a psychedelic pinwheel caught in gelatin. Everything wants to race but remains sludgy and stuck. There is no telling whether the work achieves completeness or closure. It playfully accentuates the paradox of an elegantly mounted exhibition that calls itself “unfinished.”

Many of the entries in the show take that title as an invitation to address the creative process, but occasionally one reaches into the realms of social policy and international politics. Shou Jie Eng’s Flag matches the reflexive sophistication of Rubric and Trio Disorder, but brings that self-consciousness to bear on structures of nationalism and civic polarization. The vertical banner at the core of the image has ragged, leaky borders; where we might expect a firm edge, we encounter tears and absences, transgressions and escapes. Rude streaks cut across the stripes in ways that suggest activist graffiti. Those streaks take on organized shape within and against the flag, overwriting one emblem of collective identity with another. Given those connotations, the idea of damage acquires unexpected human gravity. And the sense of something unfinished, something that begs resolution without drawing any nearer to it, becomes almost indistinguishable from grief.

So amid the happy accidents and pleasure in irresolution, there arise signals of civic urgency and reminders of art as intervention in immediate public controversies. The formal “letting go,” with its distaste for conventional borders and territories, occurs in concert with tenacious advocacy, an obdurate “holding tight” to principles associated with democracy and critical investigation. In such cases, the creative ecology or participatory environment proves much larger than the studio, intervening from places where damage is not an aesthetic question but a lived certainty. That Unfinished/Accidents can carry those contradictions without crumpling under their weight shows the precision engineering of the show, the serendipitous coordination of its relations, all of which express human agency without being reducible to it.